Dasha Krotova was heading home to her apartment in Moscow late one evening when she felt a presence trailing her from behind.

It was two policemen, who followed her to her door.

“They started to warn me and my husband about threats,” Krotova said.

Threats related to her work with Memorial, the Nobel-Prize-winning nongovernmental organization known for exposing Soviet human rights abuses, such as atrocities committed in the Gulag labor camps, or killings in Chechnya.

Krotova had been working as a photographer and editor for Memorial when the police warned her and her husband that they were on a government watch list.

The incident happened on Feb. 24 — the same day Russia invaded Ukraine.

Two days later, Krotova fled to Warsaw. She’s now one of several Memorial employees living in exile in the Polish capital, alongside dissidents and activists from all over the Soviet diaspora.

This moment has created an unexpected opportunity for the historians among them to work together to uncover the more disturbing aspects of their shared history.

Long before Russia invaded Ukraine, the history of Eastern Europe has been written and rewritten — with governments in power using their leverage to tell the version of history they prefer.

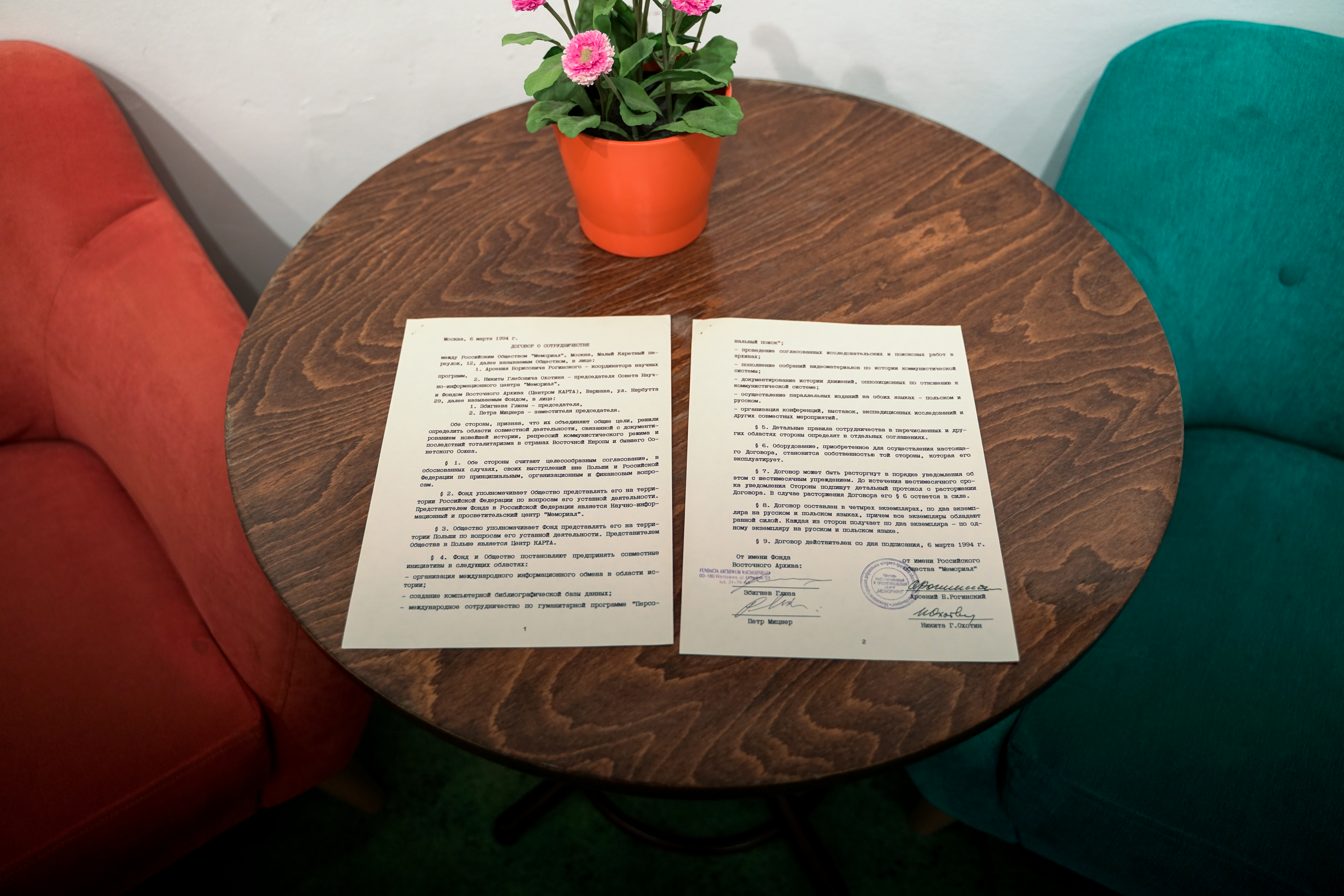

Zbigniew Gluza is the president of KARTA, a Polish nongovernmental organization with a similar mission to Memorial — to uncover the darker aspects of Poland’s past.

For 40 years, KARTA’s team of historians has been revealing concealed parts of Poland’s 20th-century history, such as testimonies from the 1940s Volhynia massacre and a database of Poles repressed in the USSR.

“History needs to be seen in the international context, so we definitely understood that having a partnership in the east would be very beneficial,” Gluza said.

Recent collaborations with Memorial have helped expose the details behind events like the 1940 Katyn massacre, in which 22,000 Polish military personnel were killed by Soviet forces.

“Thank God we have a generation of people interested in true history, not the falsified Soviet history,” said Andrei Sannikov, a member of the Belarussian opposition who has been living in exile in Warsaw for 10 years.

He said that for decades now, the government in Belarus has been censoring its own history — particularly anything that contradicts the narrative of Russia being a friend to Belarus.

“We didn’t pay much attention to the history lessons and even the tensions that we are having today,” Sannikova said.

“Not just with Russia … but even among ourselves. It is quite an indication that we have a long way to go to reconcile — even with friends.”

Friends being allies in other former Soviet countries. But Sannikov is also optimistic and believes Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has catapulted a bond between countries across the Soviet diaspora.

People aren’t just questioning the Russian version of history — but also versions of history being championed by each of their own governments.

Eugeniusz Smolar, a foreign policy specialist and former journalist, gave the example of Poland’s far-right government, which he said has been revising history when it comes to things like Polish complicity in the Holocaust.

“Poles often tend to look at themselves as the victims of history and do not recognize enough that they also occasionally behaved as the perpetrators.”

“Poles often tend to look at themselves as the victims of history and do not recognize enough that they also occasionally behaved as the perpetrators,” Smolar said.

Indeed, in 2018, Poland’s far-right government passed a law making it a crime in Poland to accuse the Polish people of being complicit in the face of German atrocities.

This, despite evidence that some acted as bystanders or even facilitated the Nazis in carrying out their mission.

The details of the real history have been well documented, thanks in part to the work of organizations like KARTA.

Gluza believes people’s appetites for that real history has only improved since the start of the war.

“For 40 years, KARTA and other organizations have been building up a certain energy that only now is being released into action,” Gluza said.

“Now, nobody wants to risk going back to the totalitarianism of the past — understanding real history may be one of the greatest tools to fight it.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!