The fuel shortage in Sri Lanka has cleared many of the cars, buses and motorbikes from Colombo’s streets. Unable to get gas to fill their tanks, more commuters are now turning to bicycles to get around.

Bike shops in Sri Lanka’s largest city have reported higher sales — with the largest domestic bike manufacturer seeing a 300% increase in demand.

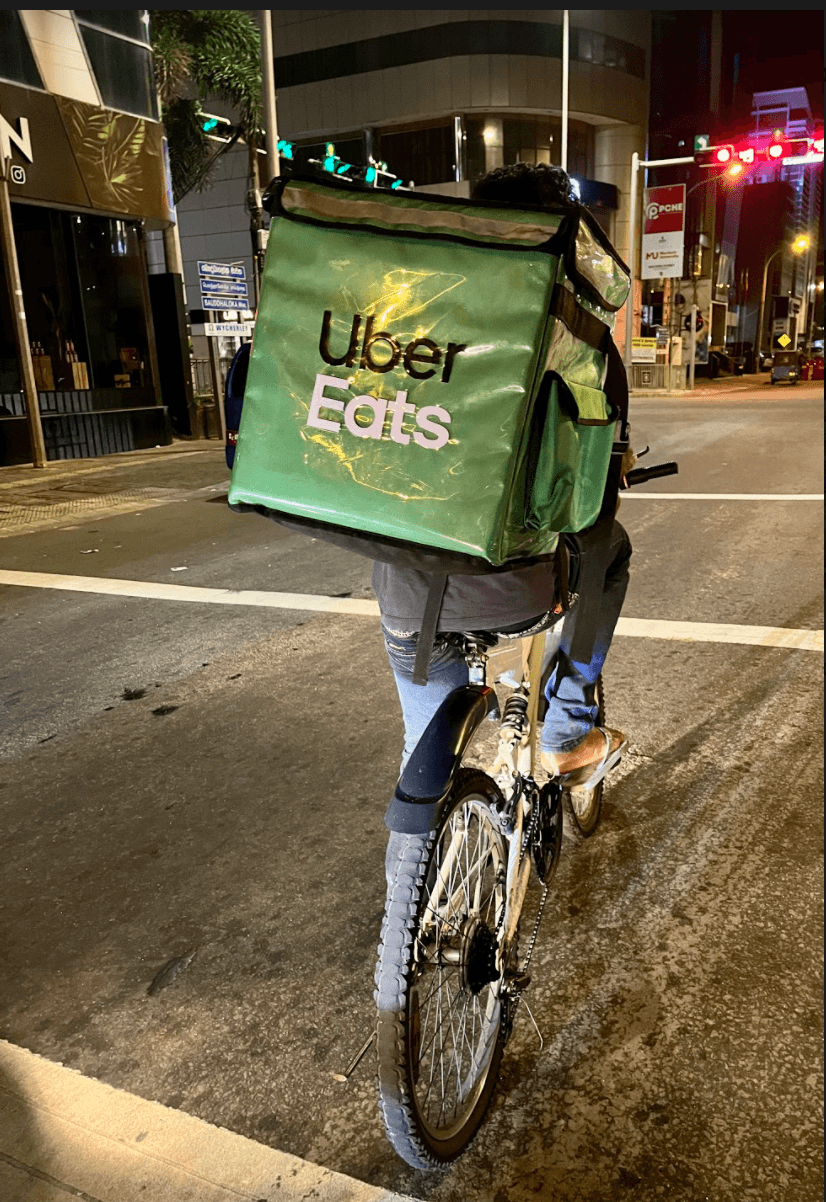

Some companies are also adjusting their delivery methods. In May and June, Uber Eats and its local competitor, PickMe, announced that they were adding bike delivery options to their apps. But that’s starting to take a toll on the people who actually have to work the streets.

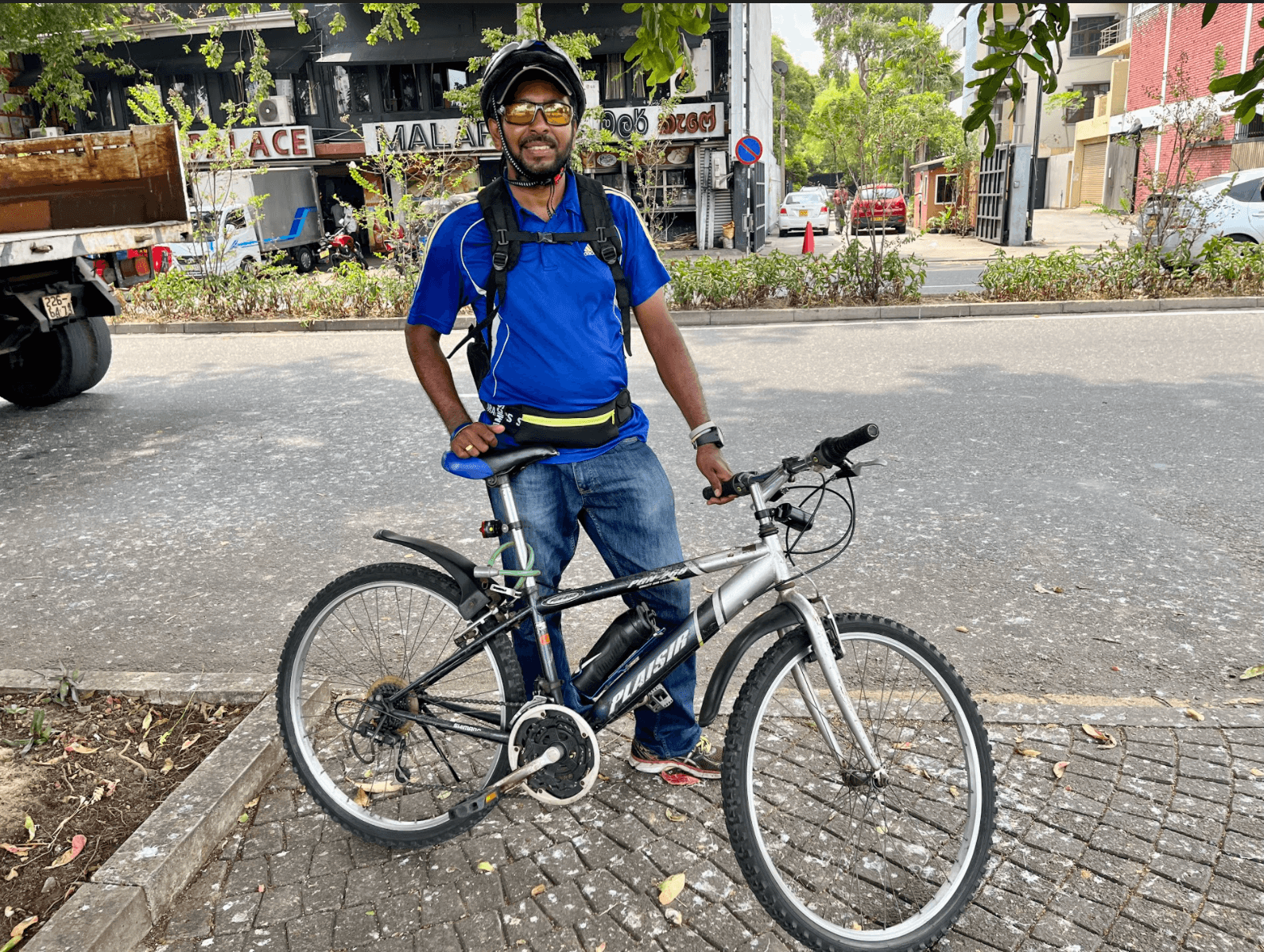

“It’s really hard,” said courier Chathuranga Rajapaksha, while biking through the city on a hot and humid afternoon, logging his 25-30 daily miles. “But there’s nothing else to do, we have to do our work.”

Rajapaksha, who wore tinted cycling glasses and a helmet, used to ride his motorbike or car to make deliveries before the country’s gas shortage woes began.

But the Indian Ocean island of 22 million people defaulted on its debt in May, and is now out of money to pay for the imports of basic necessities, including food, cooking fuel, gasoline and medicines.

And when fuel does become available, it often requires waiting in lines for days to purchase some.

Those who used to bike regularly before the fuel crisis are seeing comparatively calmer streets and an uptick in bikers as a welcome silver lining to the country’s economic crisis.

“It’s heaven compared to what it used to be,” said Mithun Liyanage, who trains cyclists and triathletes at his gym Endurance Lab. “Roads are less congested, there’s plenty of space for cyclists to get by, and it’s actually lovely right now.”

Since the fuel crisis started, Liyanage has been approached by corporations to provide bike safety training for employees, and said that demands for his “learn to ride” lessons have increased.

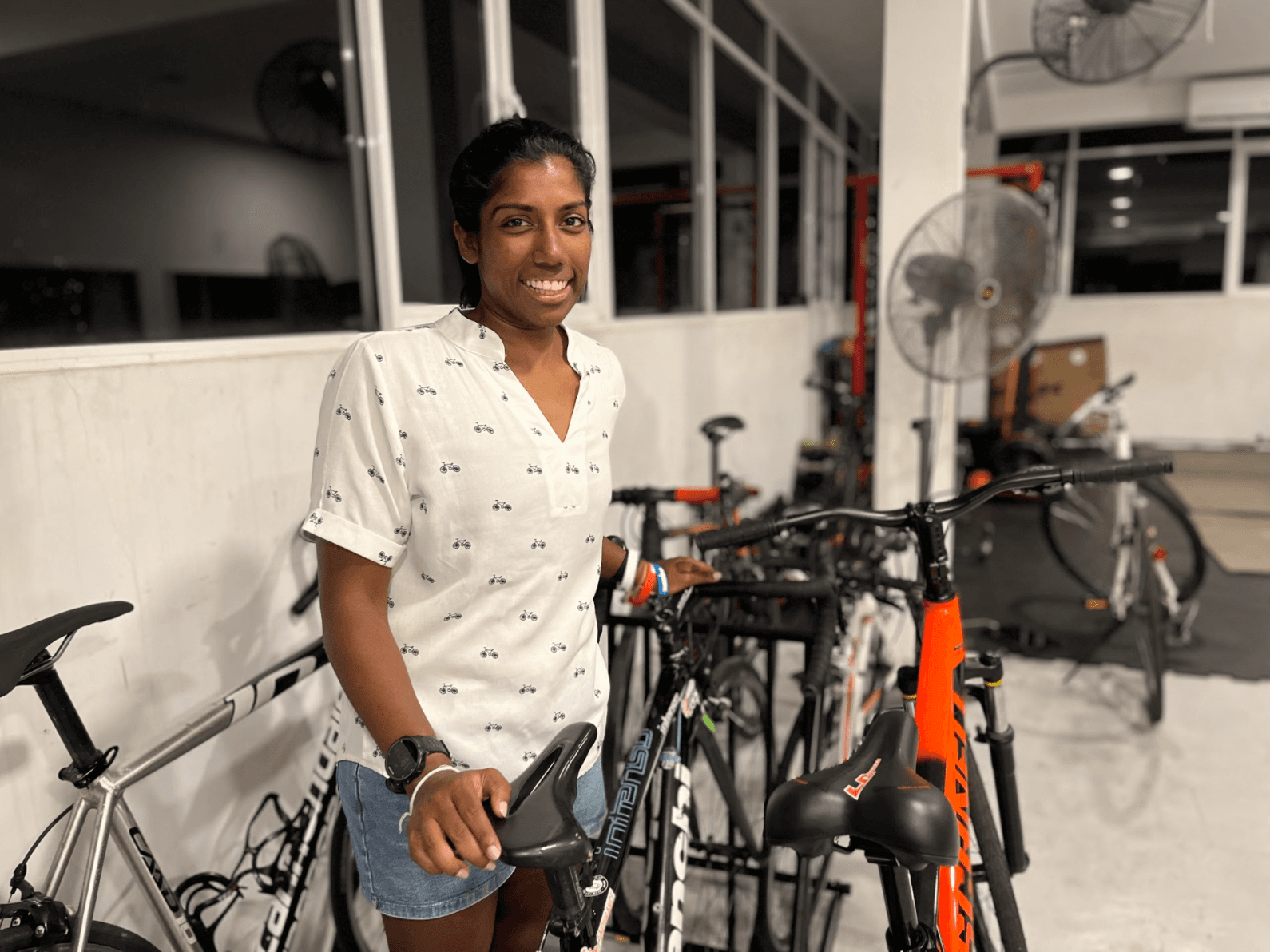

One of the riders he trains, amateur triathlete Deethri Samarajeewa, said she has become something of a bike guru for her own friends.

“So many friends have asked me, ‘Oh, where can I get a bike? I want to cycle,’ because they can’t get to places,” she said.

Samarajeewa started biking in 2019, and said her friends couldn’t comprehend why she would wake up at 4:30 a.m. to train, before Colombo’s streets were choked with traffic.

“Now, when they cycle, they’re like, ‘Oh, I get it!’”

Lumala, the country’s largest manufacturer of bicycles, said that demand has risen about 300% in the last six weeks. However, the company can’t meet those demands with the mere 12,000 bikes it produces each month. But it’s planning to increase its supply.

“We’ve expanded our production now, and will have a lot more bikes out on the market by October,” said Tariq Miflal, CEO of Lumala’s parent company. “Until then, we have simply sold out our existing stocks.”

Prices have also shot up for bicycle production, due to the higher cost of raw materials, including tires, paint and fuel.

Sajith Nasar, the manager of a bike shop in Colombo called Velo, estimated that his retail prices are up 25% to 30%.

“The supply is less, the demand is high, so the prices have gone up,” Nasar said.

The Sri Lankan government has banned the import of hundreds of items, including bicycles, in an effort to reduce the number of dollars flowing out of the country.

Many people now feel no choice but to pay these higher prices.

Mohammed Safry bought a bike in late July so that he could continue making a living delivering food, since he can’t get fuel for his motorbike. He worries about his reduced income, given that he’ll be able to make fewer deliveries. He sees his purchase as a step backward for him and his country.

“Before, we thought we have the motorbike, the next step is to buy a car. Now, it’s the reverse,” Safry said. “We have the motorbike, and now, we have to reverse to the bicycle.”

Biking has always been a popular way to get around in many parts of Sri Lanka, notably the northern city of Jaffna.

But in Colombo, the country’s largest city and financial hub, Lianage said the brand of your car has long been a status marker.

Biking, he argued, used to carry a certain stigma.

“That stigma has come down a little bit,” Lianage said. “So now, they are not looking at cycling as a poor person’s mode of transport, they are slowly changing their mindset.”

It’s not clear yet how many of the city’s new bikers will stick with it once fuel flows freely again, and how many will return to cars or motorbikes to get around — often more quickly — in Colombo’s tropical heat.

Related: Sri Lankans wait in line for days to refuel their vehicles amid shortages, economic crisis