‘We live paycheck to paycheck’: Workers at a paper factory in Beirut worry about making ends meet in a dire economy

Abdel Ghani Ghanoum has been thinking a lot about the sea lately — specifically, the waters between the coast of Lebanon and Turkey.

For 24-year-old Ghanoum, that is what stands between a life of endless struggle here in Lebanon and a chance at a more stable one in Turkey.

“We live paycheck to paycheck. No matter how much I work, I still don’t earn enough to make ends meet.”

“We live paycheck to paycheck,” he said. “No matter how much I work, I still don’t earn enough to make ends meet.”

Related: Lebanon’s electricity crisis means life under candlelight for some, profits for others

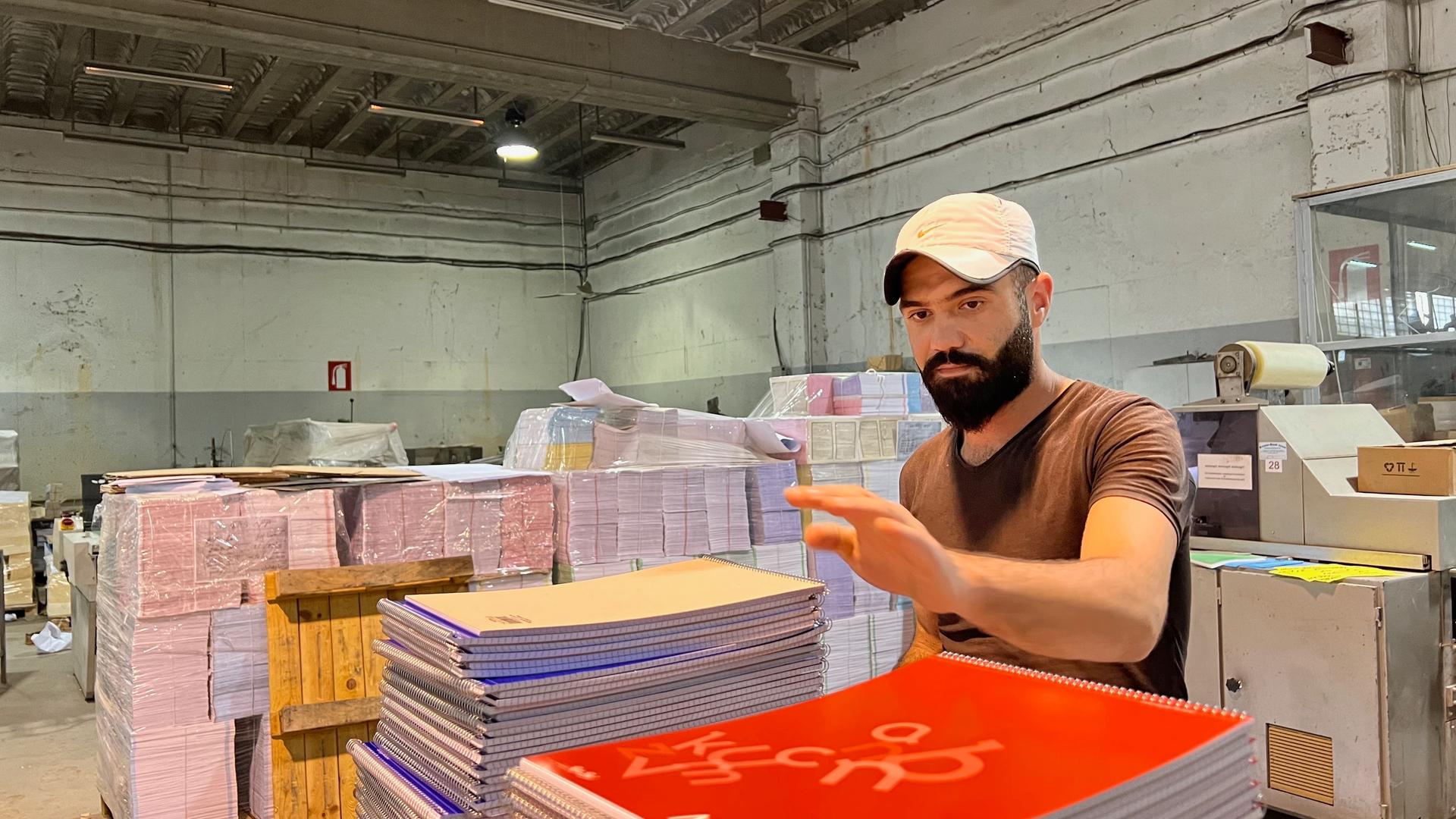

Ghanoum works at a paper factory for a company called Oriental Paper Products on the outskirts of Beirut. He is just one of many here who say they don’t see a future for themselves in Lebanon, given its dire economic situation and its political disputes with a prime export destination — Saudi Arabia. They say they are looking for a way out.

Ghanoum, who’s been in his job for a handful of years, does all kinds of work at the factory, from feeding giant rolls of paper into machines, to cutting and binding pages together to make notebooks and calendars.

He said his meager paycheck has shrunk even more in the last year or so, because Lebanon’s currency has lost its value. He makes about $85 a month, but his friends who went to live in Turkey last year tell him they are making about $400 a month working at a coal factory.

He said he has been thinking about joining them. Recently, Ghanoum found a smuggler who he said would charge him $400 to get to Turkey by boat. So, he saved up some money for the trip and borrowed the rest.

But the more he thought about it, the more he worried about the dangers.

Related: Tensions rise over Beirut blast investigation

“There are people drowning in the sea, children and babies,” he said. “Everyone is emigrating because there is nothing left [here].”

After discussing the idea with his wife, Ghanoum changed his mind. He wasn’t ready to take the risk. That is, until a few weeks ago, when he heard the news about Saudi Arabia’s ban on Lebanese imports.

His company sells many of its paper products to the kingdom. But Ghanoum hasn’t decided what to do yet.

Last year, Lebanon exported just over $200 million worth of goods to Saudi Arabia, according to Mike Azar, a financial expert and a banker based in Beirut. That included things like chocolate, paper products and jewelry, along with other metal imports.

Relations between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon have been sour for a while, he said. But tensions amplified last April when Saudi customs officials seized a large shipment of Captagon, an illegal amphetamine, hidden in a shipment of pomegranates from Lebanon.

In response, Saudi Arabia banned imports of Lebanese fruits, a huge blow to farmers. The political tension with Saudi Arabia could put another important source of revenue in jeopardy, Azar explained.

“There’s a large Lebanese diaspora in the [Persian] Gulf countries, especially in Saudi [Arabia,] and they work there and earn a living there,” he said. “But also they send remittances back home and the Lebanese economy has become really dependent on remittances. Especially in the last two years.”

These remittances, he added, make up about 40% of Lebanon’s gross domestic product.

“So, Lebanon’s relationship with the Gulf is very fundamental, at least from an economic perspective to the Lebanese economy.”

“So, Lebanon’s relationship with the Gulf is very fundamental, at least from an economic perspective to the Lebanese economy,” he said.

The impact of recent events is already having an impact at Ghanoum’s paper factory.

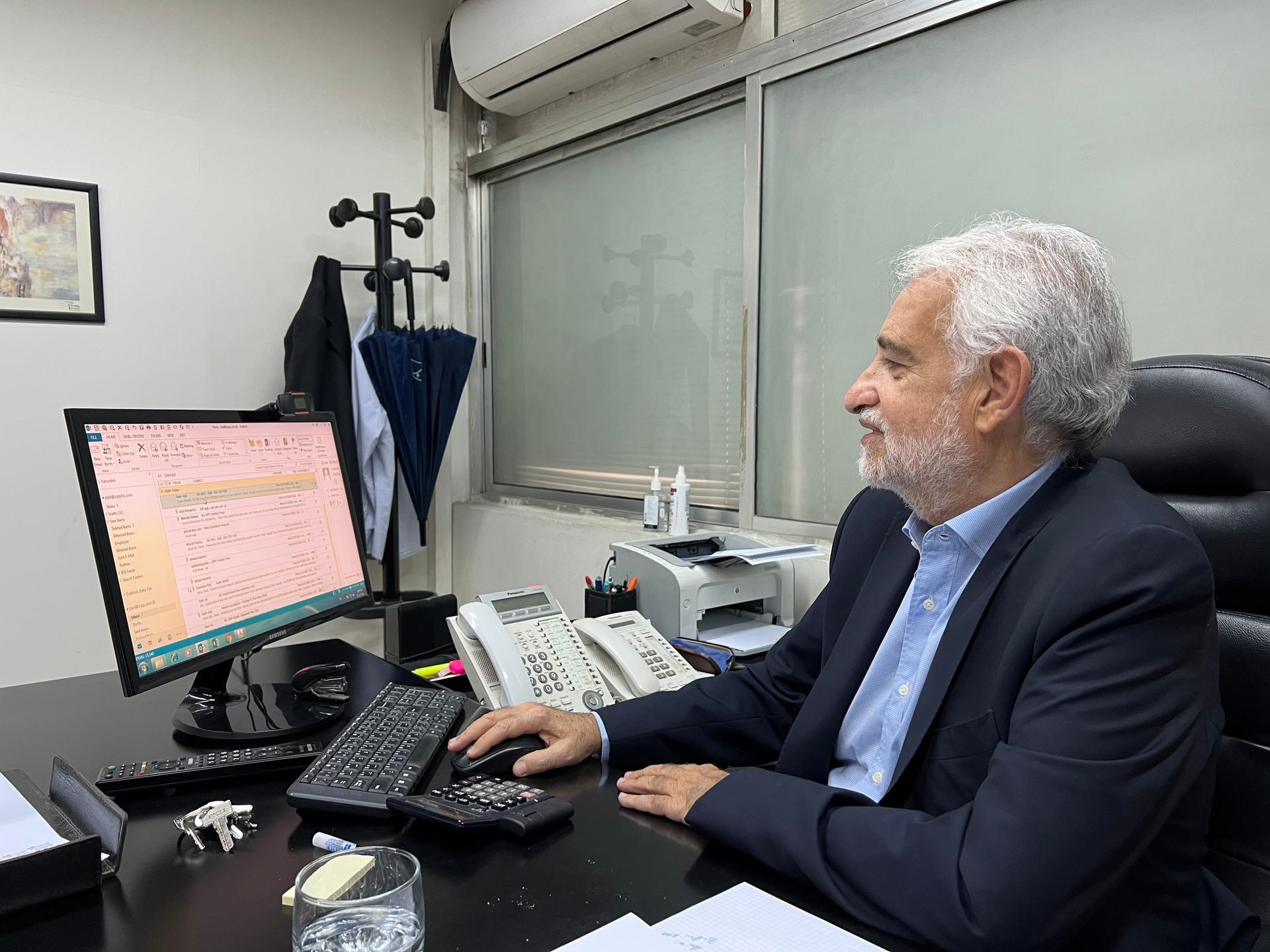

Ziad Bekdache, the CEO of Oriental Paper Products, said orders of notebooks and calendars from Saudi Arabia have been sitting in the warehouse since the announcement.

“Nobody [in Saudi Arabia] will take it, because it was a personalized order for a special client,” he said.

Bekdache, who is also the head of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists, said the company’s plan was to boost exports to Saudi Arabia to $600 million by next year. But now, everything has come to a halt.

“This is a big impact for us,” he said. “We will lose, in 2022, around $400 [million] or $500 million [in] export[s] to Saudi Arabia.”

Related: Lebanon’s crisis has gone from bad to worse. But is anyone listening?

As a result, Bekdache is considering relocating his operations outside of Lebanon. He said he needs to make a decision soon because he’s losing money.

“I was, two weeks ago, in Muscat, Oman, to find out what the opportunities [are] and the subsidies that we can get from Muscat, Oman; we’re going next week to the UAE. I’m trying to find out as well in Egypt,” he said.

It could mean laying off his 70 employees, he said.

That’s something that weighs on him.

“These people [workers] have been working with us for years, some of them have been here for 20 to 25 years. It’s not easy to close down the factory and leave them,” he said.

“I didn’t leave this country in 1975 [start of the Lebanese civil war]. It’s not easy to leave the country and I hope we will stay here.”

Ultimately, this is not the course he wants to take: “I didn’t leave this country in 1975 [start of the Lebanese civil war]. It’s not easy to leave the country and I hope we will stay here.”

Tarek Younes, who has been working as plant manager there for five years, said he’s concerned about the company’s financial situation.

He has already posted his resume on job-hunting websites and has two interviews coming up with a construction company and another at a cosmetics factory, he said.

But they’re in Ghana and Nigeria. His options are limited because, now, he cannot get a visa to Gulf countries due to the Saudi ban, he said.

“If I’m traveling to Europe, once they see I’m Lebanese, they [will say] ‘Ah, you are a refugee, maybe you are coming and not going back to your country,’” he said.

Going to the US is almost impossible, because it’s difficult to get a visa, he said. So, he’s focused on Africa.

At the same time, Younes supports his parents in Lebanon, and he worries about leaving them behind.

“The idea [that] I’m traveling is very difficult for them,” he said.

But for now, he doesn’t have much of a choice. He has to make a living, he said. If not in Lebanon, it has to be somewhere else.