Lebanon’s electricity crisis means life under candlelight for some, profits for others

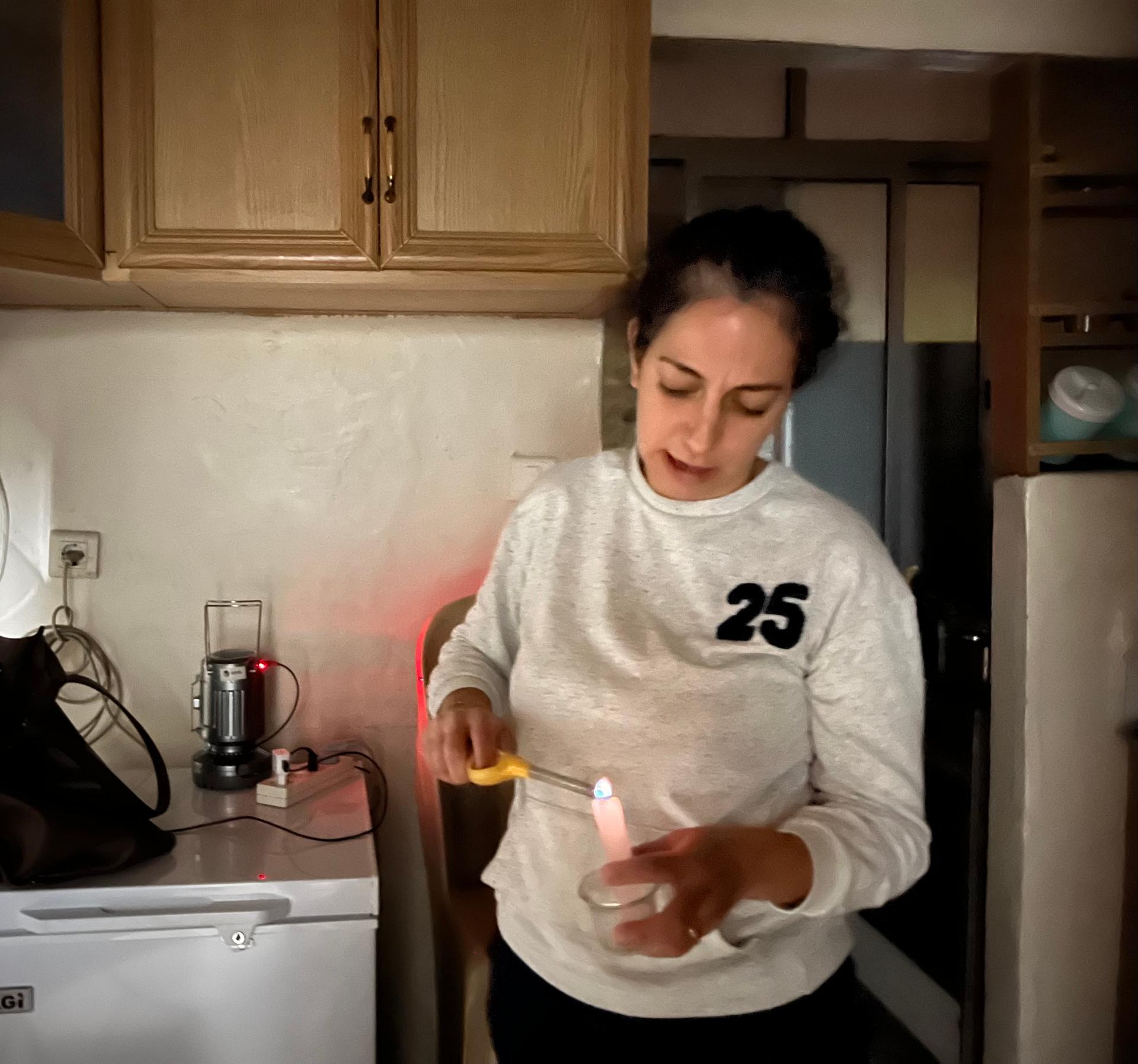

It’s around 6 p.m., and Diala Attieh Younes’ family is gathered in the living room of their house in Beirut, huddled under a single lamp to do homework and later, have dinner.

She and her husband have four kids between the ages of 1 and 11.

For the past year, this has become their daily ritual: After sunset, Younes turns everything else off, except for the refrigerator.

Related: Lebanon’s crisis has gone from bad to worse. But is anyone listening?

The family gets power from the public utility, but only for an hour or two per day. For the rest, they rely on prohibitively expensive power supplied by private generators, or, they go without.

Lebanon is facing an electricity crisis. Power outages, which have long been a part of life, have now become so common that those who can afford it pay for their own electricity through privately owned and operated generators.

Last month, after the country’s two main power stations ran out of fuel, the state electricity grid shut down entirely. Limited power was restored after the Lebanese army agreed to provide fuel distributed equally between the two power stations.

But for many, this is just a Band-Aid solution to a major crisis.

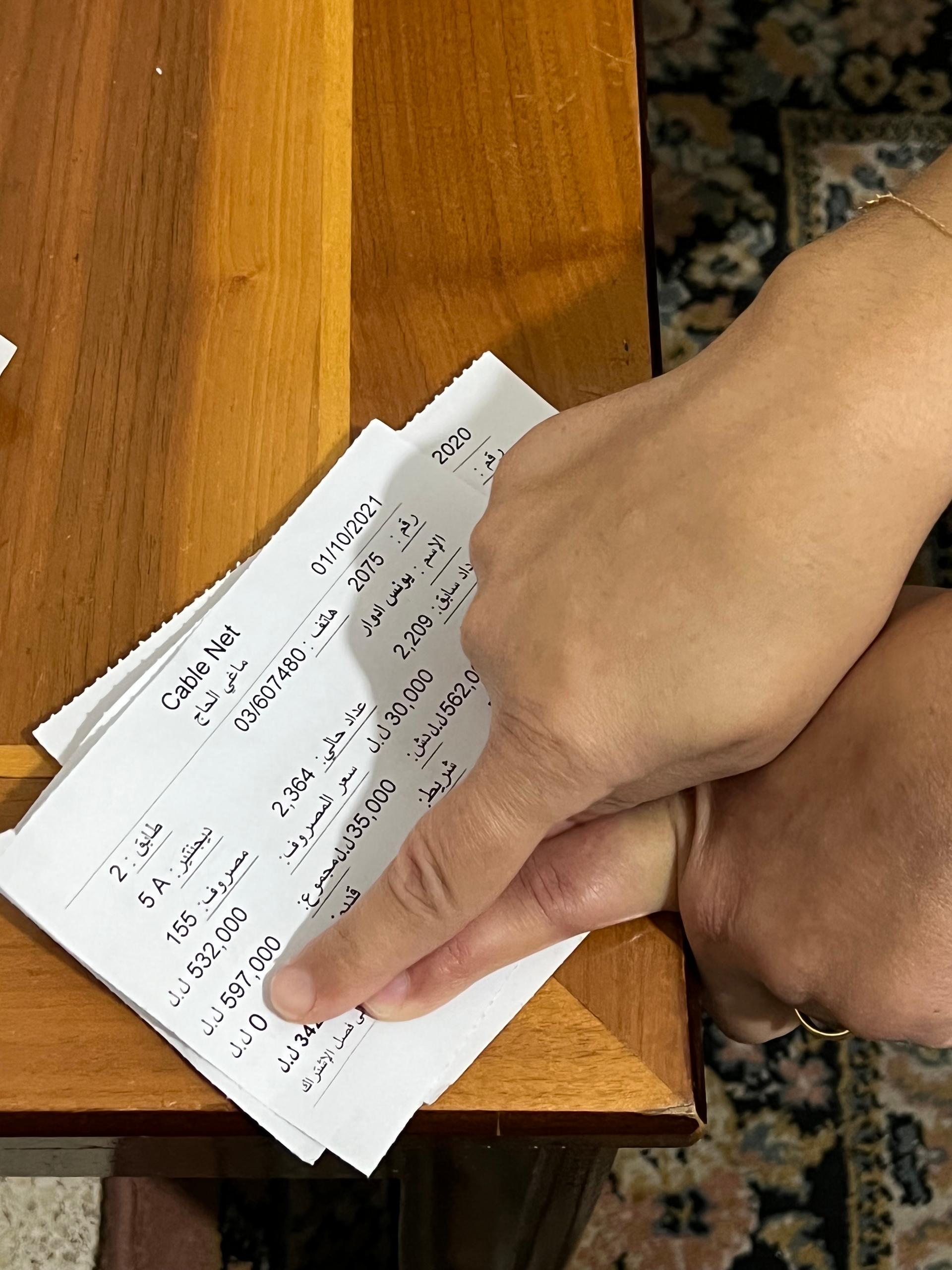

Younes showed her generator bills — her payment has gone up six times in just the past year.

Just to keep that single lamp — plus the refrigerator — running throughout the day, Younes’ family paid 579,000 Lebanese lira in October (about $25 — going by the black market conversion rate that people in Lebanon use). The minimum monthly wage in Lebanon is 675,000 lira ($34).

Younes used to be a teacher, but she lost her job at the start of the pandemic. So now, her family relies on her husband’s income. He delivers medical supplies to hospitals.

Younes said she has resorted to sweeping the floors of her home instead of vacuuming. She does laundry by hand instead of turning on the washing machine.

She said she saves energy during the day, when the kids are at school. That way, when they get home, they can turn on the light to do their homework.

Related: Tensions rise over Beirut blast investigation

In the morning, she gets the kids dressed and ready for school under candlelight. Sometimes, the government-supplied electricity comes on at 2 a.m. so she stays up to bathe the kids.

And, she has had to ask for help from her family to pay the generator bills.

“We have to put on a happy face for the kids, but we cry when we’re alone.”

“We have to put on a happy face for the kids, but we cry when we’re alone,” she said.

Economic downturn, fuel shortage and mismanagement

Power outages have long been a part of life in Lebanon. But things have been getting worse over the past year.

“The electricity sector has been one of the fastest sectors to reflect the economic crisis the country has been living in,” explained Marc Ayoub, a researcher at the American University of Beirut.

“In the late 1990s, the Lebanese government was able to provide electricity 24 hours a day. But then, they stopped investing in electricity and this gap between supply and demand started growing. This opened the door for the diesel generator market,” Ayoub said.

Privately owned generators were popular during the civil war in the 1970s. They faded away after peace took hold in the 1990s.

Nowadays, every neighborhood relies on generators.

Related: Lebanon’s political class ‘ripped off’ the country’s potential, ‘Pandora’ investigator says

In addition to the economic crisis, Lebanon is also facing severe fuel shortages.

“The public electricity utility doesn’t have any more money to buy fuel or to procure fuel for our aging and old and inefficient power plants.”

“The public electricity utility doesn’t have any more money to buy fuel or to procure fuel for our aging and old and inefficient power plants,” Ayoub said.

Aging power plants, fuel shortages and a currency that is becoming more and more useless all spell disaster for families like Younes’.

Businesses, especially smaller ones, are hurting, too.

At the Gustav ice cream store in Beirut, employee Rana Idriss said the store was forced to cut down its products because it has no way to keep them fresh. She pointed to a fridge that sat unplugged.

“We’re living month to month; we don’t know how we can survive like this,” she said.

The power cuts couldn’t have come at a worse time for this store. The business was already losing profit because of the economic downturn. Idriss said few people can now afford luxuries like cake and ice cream.

“I am working here, I cannot buy from here anymore. It’s too expensive for me. Because I get my salary in Lebanese lira. That’s why,” she said.

She lists the types of cakes they make — lavender, gluten-free, red velvet and “divorce cakes,” which have become more popular recently, Idriss said.

‘We fill a gap left by the government’

Forty-five-year-old Michael owns and operates two generators in one of the Ashrafiyah neighborhoods in Beirut.

Related: Beirut blast one year later: No justice, no hope

Michael asked that his full name not be used because he said the government puts pressure on operators who speak to the media.

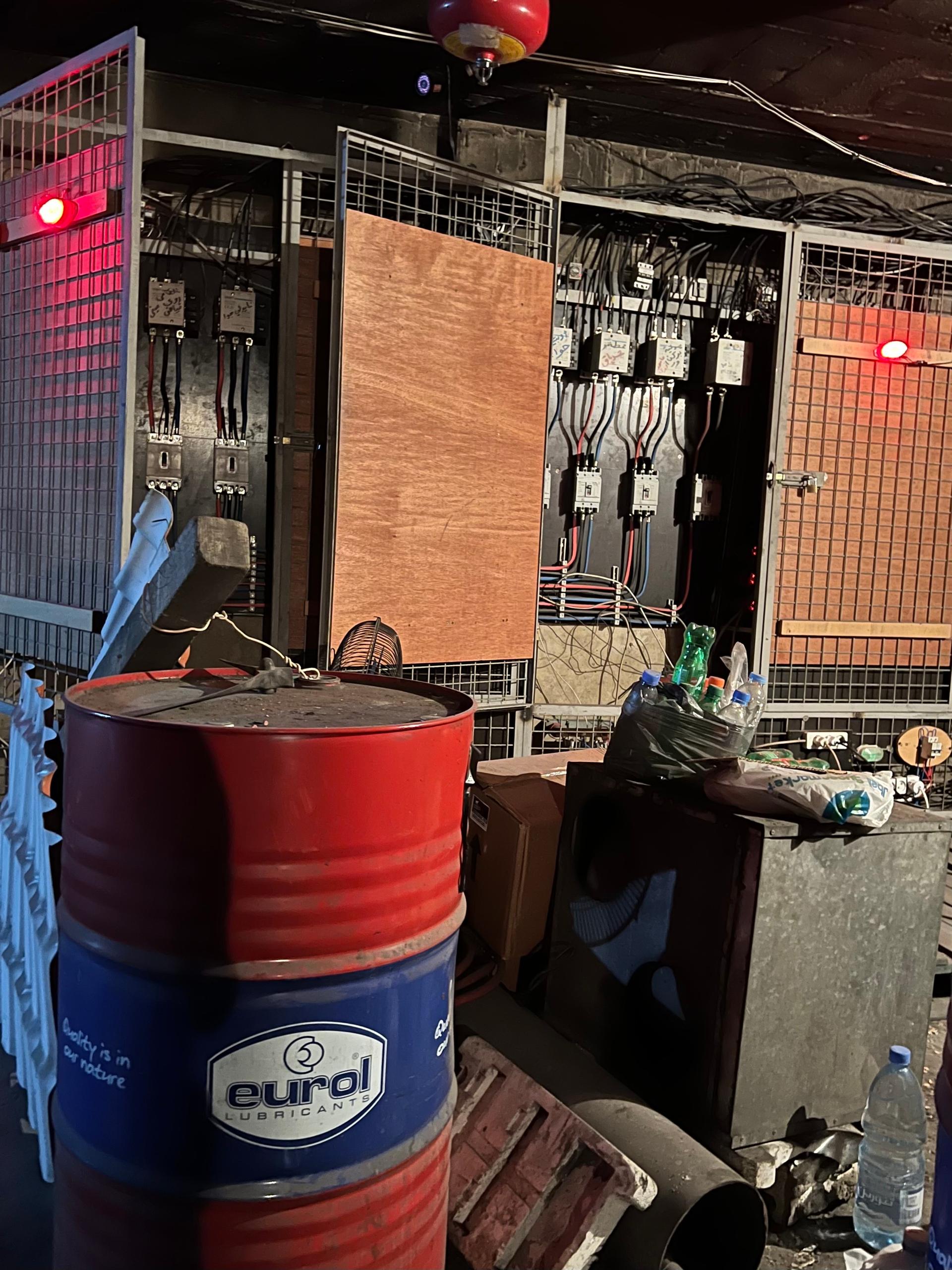

Michael spoke from his workshop, where tools hang on the wall. The generators are in the basement of what looks like an abandoned building.

It was pitch black, so he turned on the lights on his cellphone. Inside the building, the noise of the generators got louder and louder as he walked two floors down.

Shortly after, he reached a huge metal box with cables and switches inside. Michael has labeled each switch with the name of the street that it powers. The labels say things like, “The street with the pizza shop” and “The one with the grocery store.”

Before the recent crisis, Michael used to run the generators only for a few hours a day. And only for those businesses that couldn’t withstand short interruptions.

Now, he said, he runs them almost all day — except for a few hours needed to cool them down and to maintain them.

There are hundreds of people like Michael who run generators all over Lebanon, said Ayoub, the researcher at the American University of Beirut. Ayoub added that in 2018, the last data available, there were an estimated 34,000 to 40,000 generators distributed across the country.

Some businesses are smaller than the others, he said, but none are regulated by the state.

“They have their own networks, they have their own billing system, subscribers and you see, people cannot [have no choice but to] pay,” he said.

Recently, as demand for generators went up, the Lebanese media started criticizing generator suppliers, Michael said.

They accuse them of operating like the Mafia, overcharging customers and claiming their own turf.

Michael denied these accusations.

Michael charges between 700,000 to 900,000 lira per ampere (the unit of electric current). A house with air conditioning and a heater, he said, will require 10 amperes. That is a total of 7,000,000 to 9,000,000 lira.

“Some people call us a mobster because they don’t know what we are. We are people. Normal people.”

“Some people call us a mobster because they don’t know what we are,” he said. “We are people. Normal people.”

He said he is simply filling a gap left by the Lebanese government.

“We did not cause the problem of the electricity. We are the solution [to] their mistake.”

In fact, Michael says he has been losing money. He buys diesel — to run the generators — with US dollars, but he gets paid in Lebanese lira, which has dramatically lost its value.

Plus, he said, if it wasn’t for him, businesses like the dentist in his neighborhood would have to shut down entirely.

Meanwhile, Younes said she has been trying to figure out ways to bring down the costs of the family’s generator bills. She has learned a lot about candles — the ones made with beeswax last longer.

She said that if things continue as they are, she will be relying on candles even more.

It’s hard, but she said she’s trying to stay strong for her kids.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?