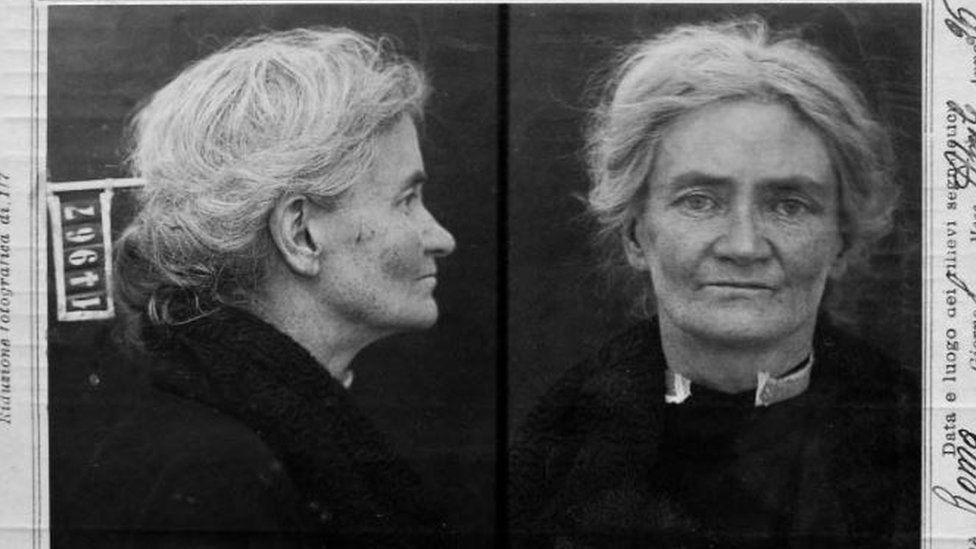

Violet Gibson — a 50-year-old Irishwoman, 5-foot-1 with long, graying hair — was an unlikely assassin.

On the day she shot Benito Mussolini, April 7, 1926, the Italian dictator had just spoken at an international conference of surgeons in Rome, and was making his way through the cheering crowds in Piazza del Campidoglio back to his car.

Siobhán Lynam, who made a radio documentary about Gibson, said the tiny, slightly disheveled-looking woman just raised her gun and shot him at point-blank range.

At that same moment, students nearby had started to sing a fascist song in tribute to Mussolini. The Italian leader turned his head toward the students, and the bullet grazed his face, taking a chunk out of his nose. Gibson fired again, but this time, the bullet jammed in the barrel of the gun.

The Irishwoman was dragged to the ground by an infuriated mob, and it was only with police intervention that she was saved from serious injury. Nobody knows if Gibson acted alone.

Although the assassination attempt made international headlines, for decades, Gibson was all but forgotten. Now, following the 2014 radio documentary, a new film and a biographical book about Gibson, Ireland is looking to honor her in a public way. Dublin plans to install a plaque on the wall of Gibson’s childhood home in Merrion Square in the city center.

Related: Activists took the Irish govt to court over its national climate plan — and won

Dublin City Councillor Mannix Flynn proposed a motion that Gibson be brought “into the public’s eye and given her rightful place in the history of Irish women and in the rich history of the Irish nation.”

Flynn said Gibson needs to be honored as a political prisoner.

“Given what we know about the Second World War and what Mr. Mussolini did, surely it’s time that the establishment that so condemned this individual should bring Violet Gibson into the open.”

“Given what we know about the Second World War and what Mr. Mussolini did, surely it’s time that the establishment that so condemned this individual should bring Violet Gibson into the open,” Flynn said.

Flynn said Gibson’s parents were powerful British imperialists who were ashamed of her actions and tried to silence her “in the same way we see people canceled today.”

“Basically, way before we had the ‘cancellation generation,’ this was how people were canceled,” Flynn said.

An embarrassment for Mussolini

Mussolini was a hugely popular figure not only in Italy, but also among global leaders. After Gibson shot him, letters of concern for his well-being arrived from around the world.

“The pope sent a message saying that he was really relieved that Mussolini had been spared by God. The president of the United States sent a telegram, as did King George of England and the presidents of France and Germany,” Lynam said.

Related: The movement to restore the memory of Spain’s forgotten women artists

W.T. Cosgrave, president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, wrote to Mussolini, congratulating him on his survival.

But Mussolini wanted little attention to be paid to the attack or his would-be assassin. Hours after the shooting, Mussolini reappeared in public, a bandage across his nose.

Related: Northern Ireland still divided by peace walls 20 years after conflict

Frances Stonor Saunders, author of “The Woman Who Shot Mussolini,” said the Italian dictator was embarrassed by the assassination attempt — not only because his security had failed to protect him, but that he had been shot by a woman. Mussolini survived four assassination attempts on his life, but it was Gibson who came closest to killing the Italian dictator.

“He was very misogynistic, as was the entire fascist regime. He was shocked to be shot by a woman. And he was shocked to be shot by a foreigner. It was a kind of injury to his great ego.”

“He was very misogynistic, as was the entire fascist regime,” Stonor Saunders said. “He was shocked to be shot by a woman. And he was shocked to be shot by a foreigner. It was a kind of injury to his great ego.”

Mussolini didn’t want Gibson to be put on trial in Italy — it would draw further attention to her. A deal was done to deport her back to England. When she arrived in London, Gibson’s sister took her in a cab to Harley Street, where she was met by two doctors.

They declared her lucidly insane and with the consent of her family, Gibson was sent to a mental institution in Northampton. Stonor Saunders said Gibson did have mental health issues in her past and had suffered nervous breakdowns.

Even so, it was convenient for the Italian dictator to portray her as a madwoman rather than someone who was outraged by his politics. The treatment of Gibson was typical of the conversations around madness and women in the 1920s, Stonor Saunders said.

“It excluded the possibility that you could be mad or have what is conventionally described as moments of madness, but that you can also have completely legitimate political ideas,” Stonor Saunders said, adding, “And she did.”

Gibson was a difficult woman to deal with, and it suited Mussolini, the British and Irish authorities, and her family to lock her away, she said.

Gibson had been born into a life of privilege at a time when Ireland was still under British rule in 1876. Her father, Lord Ashbourne, was lord chancellor of Ireland, the most senior judicial figure in the country.

At the age of 26, Gibson brought shame on her Anglo Irish family when she converted to Catholicism. In 1913, she moved to Paris, working for pacifist organizations. For years, while Gibson was kept at the asylum in Northampton, she wrote letters pleading for her release, including to Winston Churchill and Princess Elizabeth, today the queen of England.

But the letters were never posted. Gibson died in the institution in 1956 at the age of 79, and was buried with a simple headstone that bore only her name, her date of birth and date of death.

Stonor Saunders said no family members attended her funeral.

“Even in her death, she was a great embarrassment,” she said.

Honoring Gibson’s memory

It was decades later that British historian Stonor Saunders was reading a lengthy biography of Mussolini and came across one sentence that mentioned he had been shot by an Irishwoman.

Stonor Saunders was intrigued by Gibson, this woman who had been written out of history and “derided as a mad Irish spinster.”

Mussolini’s other assassins were all men and were released after the dictator was killed. One of his attackers, Anteo Zamboni, has a street named after him in Bologna.

Lynam, who made a radio documentary about Gibson in 2014, said she doesn’t think the Irishwoman would have been forgotten if she was a man.

“Certainly, she would have been remembered. I think it was just indicative of how women were treated in history.”

“Certainly, she would have been remembered. I think it was just indicative of how women were treated in history.”

Now, Gibson’s descendants want her to be remembered too, filmmaker Barrie Dowdall said.

“Violet Gibson, the Irish Woman Who Shot Mussolini,” Dowdall’s new film, is currently showing at film festivals around the world. The director says he believes the Gibson family is proud to have this woman as part of their history.

“They want her to be seen as a woman who stood up against the sins of fascism.”

Dowdall, who’s looking for distribution rights so his film can screen globally, said people need to know that if Gibson had killed Mussolini, she might have changed history.

Stonor Saunders agreed: “She should be celebrated as a brave woman, as a political radical, as an antifascist. And if she was mad, well, she still saw something before anyone else did.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?