Spain’s María Blanchard is often compared to Mexico’s Frida Kahlo. Both women gained worldwide success as painters in the early 20th century and had physical disabilities that dictated themes in their art. They were also both close with fellow Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who was married to Kahlo.

Related: Meet Doña Luz Jiménez, the forgotten indigenous woman at the heart of Mexico’s cultural revolution

But unlike Kahlo, who is a household name and whose likeness can be seen in countless self-portraits and a wide range of merchandise, Blanchard has been essentially erased from history books.

“That happened to many female painters of the time. You see an exceptional painter and you wonder, why didn’t she get any recognition? And you come to the sad realization that it was because she was a woman.”

“That happened to many female painters of the time,” said art historian María José Salazar, who did her doctorate research on Blanchard. “You see an exceptional painter and you wonder, why didn’t she get any recognition? And you come to the sad realization that it was because she was a woman.”

In 1981, Salazar became the first person to curate an art exhibit dedicated entirely to Blanchard’s work. She then spent decades recovering hundreds of Blanchard’s lost paintings — some of which ended up in private collections — and showcased them at prominent museums, like Madrid’s Reina Sofía. To this day, unearthed Blanchard paintings continue to surface.

Salazar is part of an ongoing effort in Spain to recognize the country’s female painters that have been virtually lost to history. Despite the popularity of the likes of Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí, the female artists who formed an integral part of these historic art movements have not been given the same kind of attention as their male counterparts.

Related: Nude statue honoring Mary Wollstonecraft in London sparks backlash

Many of the women artists who made a name for themselves in the early 20th century and other periods have long been kept out of the spotlight. Some historians, museum curators and artists and writers are trying to change that.

A novel was released this month about Blanchard’s life, written by Baltasar Magro. There was also a song released about Blanchard by a Spanish band called La Mala Hierba back in April. And Spain’s national art museum, El Prado, is currently showcasing women artists who came before Blanchard’s time.

Artwork as a way to cope

Blanchard (whose original last name was Gutiérrez Cueto) was born in 1881 with a deformed spine and bilateral hip disarticulation. She came from an upper-class family in Salamanca, Spain, and from a young age, her father encouraged her to use her art as a way to cope with the hardship of being bullied.

Related: Centuries ago, Spanish writers challenged gender norms and barriers

After studying in Madrid’s top schools, Blanchard moved to Paris in 1909 with a government grant that helped advance her art career. There, she became an essential part of the buzzing 1920s Paris art scene and shared an apartment with Rivera and his first wife, Angelina Beloff — also a painter. (Rivera painted them together in his 1914 cubist piece, “Portrait of Two Women.”)

“In Paris, Blanchard is free. She’s accepted into the men’s world as an artist.”

“In Paris, Blanchard is free,” Salazar said. “She’s accepted into the men’s world as an artist.”

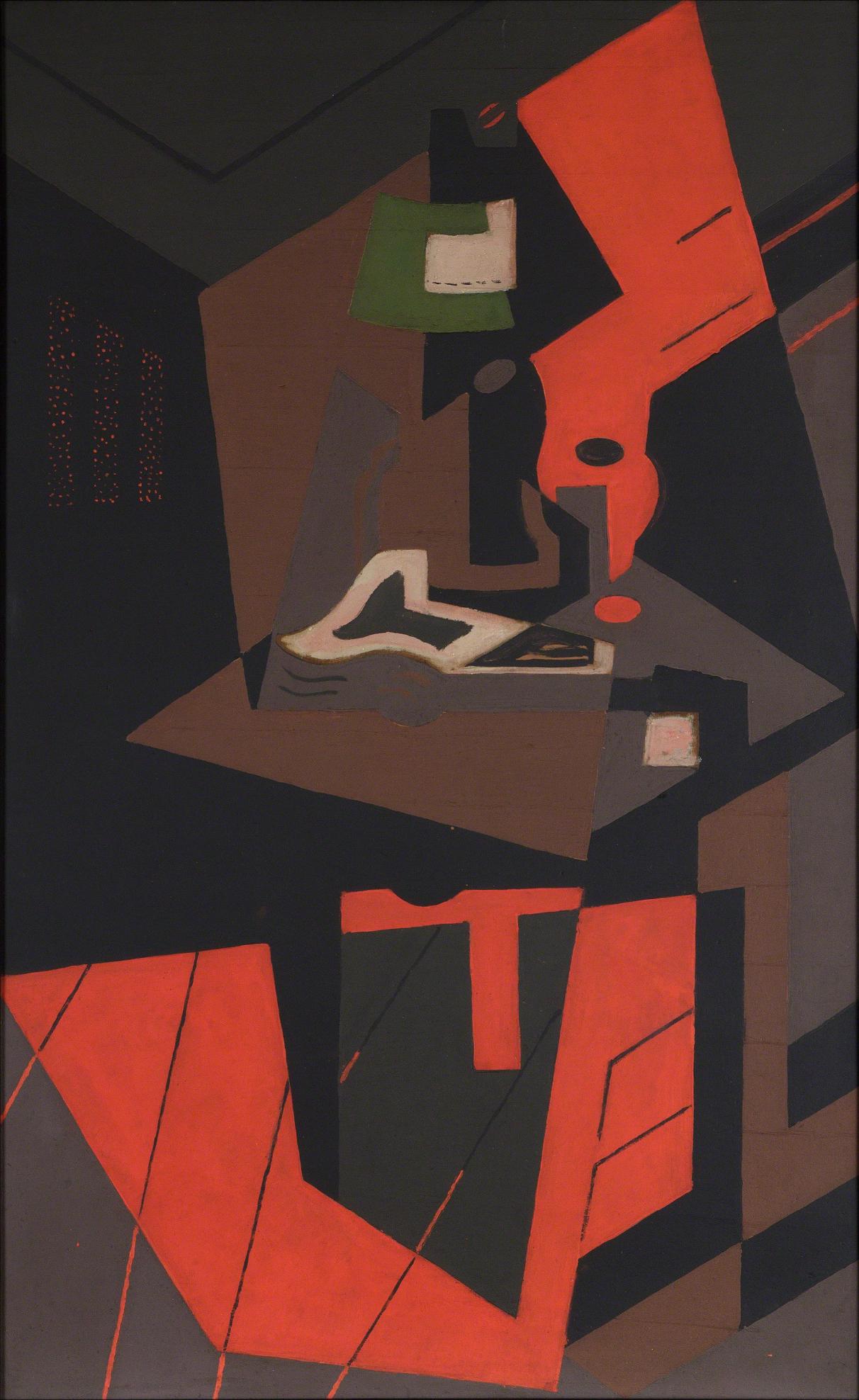

It didn’t take long for Blanchard to become a renowned cubist painter, forming friendships with Picasso and showcasing her artwork in prominent galleries alongside cubist painter Juan Gris, also a close friend.

Following her death in 1932, Blanchard’s sister pulled her entire collection out of galleries and got rid of her various art dealers, eventually selling the work to make extra money. Some of Blanchard’s paintings have since been mistakenly attributed to Gris.

Salazar says Blanchard’s work is often considered an “imitation” of her male colleagues’ paintings — when in reality, she was working alongside them.

“Paintings done by women are just as good as the ones done by men.”

“Paintings done by women are just as good as the ones done by men,” Salazar said. “In some cases, I think female artists bring a sensibility and exquisiteness that men don’t. But that’s sometimes misinterpreted as feminine weakness. These aren’t women who paint little flowers to pass the time, this is a sensibility that comes from an interior conscience as a painter.”

Related: Black history is ‘integral part’ of British culture, says historian

‘Ideological bias’ in museum collections

Blanchard is just one of many Spanish female painters who have been overlooked, Salazar says — which is why she insists it’s crucial for museums and art institutions to teach these artists’ work.

That’s something that El Prado is trying to address. Its newest exhibit, “Uninvited Guests,” which will last until March and can be visited both in-person and virtually, showcases paintings from the 19th century done by women and explores the representation of gender during that period.

Curator Carlos Navarro says these paintings give viewers a glimpse into what kind of society Spanish institutions of the time were trying to uphold.

“We thought it was important to look at the ideological bias behind our collection.”

“We thought it was important to look at the ideological bias behind our collection,” he said.

Related: Art, poetry and … zombies? The surprising cultural contributions of the 1918 influenza pandemic

All of the artwork included in the exhibit comes from El Prado’s own 200-year-old collection — many paintings had been in storage for decades. Navarro says that while some of the artwork bought by El Prado in the 19th century was done by women, the museum only selected female artists who painted flowers or still life. Many of the paintings done by men, on the other hand, had a sociopolitical message that perpetuated gender stereotypes — like the depiction of the “fallen woman,” meant to dissuade women from traveling alone.

“The artists of the time expressed themselves with liberty, but it was the Spanish state that selected which works of art would be awarded or bought for museums.”

“The artists of the time expressed themselves with liberty, but it was the Spanish state that selected which works of art would be awarded or bought for museums,” Navarro said. “They claimed to choose them because of their artistic quality, but most of the time, they were chosen for their ideological message.”

That message, he adds, was an essential part of the 19th-century mentality, which held Spain in an imperialist light, celebrated the bourgeois class and designated women to the private sphere. The exhibit, then, is a self-critique of El Prado’s contribution to the “official narrative” that was accepted and disseminated at the time.

As a result, their collection of female artists is not representative of the 19th century, Navarro says, since many artists were excluded from El Prado’s galleries because of the women’s personal lifestyles or their paintings’ subjects. Navarro said that today, every museum “should be implicated in recovering the memory of the female artists” that the state sought to forget.