Sakhone Lasaphangthong wants people to notice him.

“Oh, they know it’s me,” he said while walking the streets of Oakland’s Chinatown. “I’m almost 6-foot, bald-headed, with glasses on. You know when they see me, I stand out.”

He sees this as a good thing. He wants people to ask him for help.

Related: A Black radio host calls on South Asian Americans to reject racism

Sakhone is the director of housing services at Family Bridges, a nonprofit in Oakland, California, and he’s also part of the area’s Community Ambassador program.

Community ambassadors walk the streets of Chinatown to care for the neighborhood and help residents feel safe. They do things like sweep sidewalks, fix kids’ bikes and help with vaccine clinics.

Attacks against Asian Americans have increased across the country over the last year — including racial slurs shouted in public, kids bullied in schools, and most recently, the unpredictable attacks on older Asian Americans. Some say the uptick can be linked to rhetoric used by former President Donald Trump, who dubbed the coronavirus the “China virus” in public remarks.

An 84-year old man from Thailand was attacked and knocked to the ground during his morning walk in San Francisco. He died two days later. In another incident, a 61-year-old Filipino American was slashed in the face on the New York City subway.

Oakland’s Chinatown has also seen attacks like this. In a virtual tour of the area via FaceTime, Sakhone shows the spot where a 91-year-old man was shoved to the ground a few weeks ago. He said he regrets that he wasn’t there to help.

“Yeah, if I see them fall down, I’ll rush to help,” Sakhone said. “I always keep an eye on them.”

Related: Backlash over anti-racist billboard challenges Houston’s Vietnamese American community

Sakhone walks the streets of Chinatown every morning as shopkeepers set up their fruit stands and seniors take their morning strolls. He greets many of them by name.

A grocer runs over to give him a bag of fresh oranges when he spots Sakhone coming down the street. Take it, he gestures with his hands. Sakhone will share it when he brings a cup of coffee to a man sleeping on the streets a few blocks away.

Most residents here speak Cantonese, but Sakhone, whose family is from Laos, does not. Yet, they still manage to communicate by tapping him on the shoulder or waving him over when they need help — like the time an elderly woman had her walker stolen.

Sakhone and the woman went in search of it together but her knee buckled every few steps as they canvassed the streets. Eventually, he bought her a new walker, he recalled.

“A lot of folks are worried. … But at the same time, when I’m around, they know that I’m there to help look over them.”

“A lot of folks are worried,” Sakhone said, and some older residents aren’t even leaving their homes with the rise in attacks. “But at the same time, when I’m around, they know that I’m there to help look over them.”

Just the presence of ambassadors like Sakhone seems to make a difference.

Related: Racism against African Americans in China escalates

But building this kind of trust took time given that the Community Ambassadors initiative didn’t start as a neighborhood watch program. It started in 2017 to help give former inmates from San Quentin prison the opportunity to do dignified work and rebuild relationships with the community.

Sakhone had been incarcerated for 20 years before he was released in 2018. To stop crime, he said you need to know whyit happens. He explained how in the pandemic, people have lost their jobs, rent prices in Oakland and elsewhere have skyrocketed, and many people have lost their homes, too. All these stresses can compound mental health.

“They have no right to do it, but it’s like one way that folks express their traumas and their hurt or their pain is to take it out on people,” Sakhone said. “And it’s not right. But the pandemic is hard for every community — it’s hard for everyone.”

Related: Xenophobia ‘takes its toll’ as Trump works to curb immigration

A special police task force is being developed to address hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Oakland. But some community members say that in reality, most people here won’t call the police given a history of mistrust and lack of response.

“I don’t believe in more policing, I believe in more communication so that we could avoid these kinds of hate crimes from happening.”

“I don’t believe in more policing, I believe in more communication so that we could avoid these kinds of hate crimes from happening,” Sakhone said.

Many residents want justice for hate crime victims, while advocates like Sakhone believe in restorative justice. When he sees conflict or tension, he tries to deescalate the situation by understanding the perspectives of all those involved.

“One of my approaches is to ask if they’re OK. You know, ‘What’s going on? What do you need?’” he said.

Once home to immigrants and working-class families, the neighborhoods around Chinatown are gentrifying and now boast luxury condos, as well. Some locals say that people don’t know each other, and don’t look out for each other the way they used to. Rebuilding these relationships, they say, would help make the neighborhood safer.

Related: COVID-19 racial stats: A ‘double-edged sword’ for some marginalized groups in Canada

Beyond the noodle shops, fruit stands, some of the best dim sum in the Bay area, and a church with closed doors and a quiet playground, there’s Madison Park, where a dozen elders perform their morning tai chi.

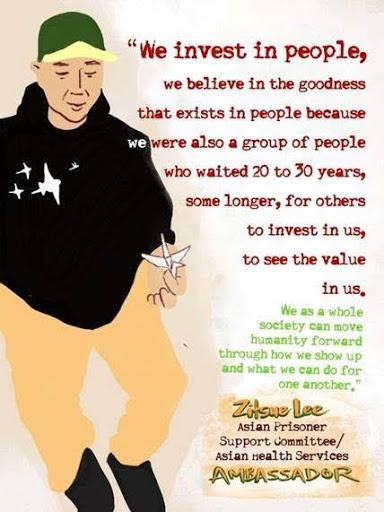

Here, Sakhone’s friend, Lee Zitsue, another community ambassador, waited for a grandmother shopping for groceries nearby, so he could walk her home.

They often say they’ll take 15-20 minutes, but it’s more like 30-40 minutes, he chuckled.

When he went to pick her up at the store where she’d been shopping though, he couldn’t find her.

“Oh man, now you got me scared,” Lee said. “I’m scared that she got lost. It’s just the opportunity for crime is so high.”

Lee went out to look for her and learned later that she had left on her own, eager to get back home.

With the weather getting warmer and people getting vaccinated, Chinatown will grow busier soon. Some fear this means they’ll see more hate crime, so the ambassadors say they’re looking for more volunteers.

Special thanks to the organizations which support the Community Ambassador program and contributed to the reporting of this story: Asian Health Services, Asian Prisoners Support Committee, Chinatown Improvement Initiative, Oakland Chinatown Coalition, Asian Pacific Environmental Network, East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation.