The pandemic has shown how a tiny virus can turn the world upside down, but it’s also ushering in a new era of science that many hope will help combat other deadly infectious diseases.

One kind of genetic technology that has been in the works for decades — DNA vaccines, which use engineered DNA to induce an immunologic response — is finally making its debut for widespread use in people this fall in India.

Related: First WHO-backed malaria vaccine is a ‘dream for the community,’ health expert says

The Indian government authorized the ZyCoV-D vaccine in August. It’s one of about a dozen DNA vaccines that are in trials for COVID-19, though just a handful are in the final phases. India is expected to roll out ZyCoV-D this month, once officials have finished negotiating prices and working out other logistics.

The vaccine has been a national point of pride. Prime Minister Narendra Modi boasted about authorizing the world’s first DNA vaccine during his speech at President Joe Biden’s vaccine summit at the UN last month.

Researchers at Zydus Cadilla, a company in western India, developed the vaccine that doesn’t need super-cold freezers. It comes in three doses. Instead of a needle, it uses a special fluid jet that punctures the skin with lab-produced DNA. The vaccine underwent a trial of nearly 30,000 people. It’s the only approved vaccine in India for children 12 and up.

Dr. Sharvil Patel, Zydus’ managing director, told CNBC International last April that this type of vaccine is extremely safe and will allow earlier adoption of any strains or variants created.

The company reported it’s 67% protective, though that research has yet to be published and reviewed independently.

How it works

The point of any vaccine is to train the body’s immune systems to recognize and fight off a virus. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the vaccines train cells to identify the virus’s outer spike protein.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, as well as Sputnik and Johnson & Johnson, all do this using viral vectors to transport genetic information. That involves deactivating and reengineering a virus to contain the genetic material or code for part of the coronavirus.

Related: Australia to lift 18-month COVID-19 travel ban next month

“You can think of it like a Trojan horse sending the spike gene into our cells.”

“You can think of it like a Trojan horse sending the spike gene into our cells,” said Shahid Jameel, a virologist at Ashoka University, north of Delhi, and at Oxford University in the UK.

Once in our cells, that spike gene produces RNA, a single-stranded molecule that translates that genetic information to make the spike protein. That allows the body to increase its immune response, Jameel explained.

The DNA vaccines are different in that they don’t use a viral vector. Instead, the vaccine sends plasmid DNA circles that introduce the genetic code for that spike protein into cells to instigate an immune response.

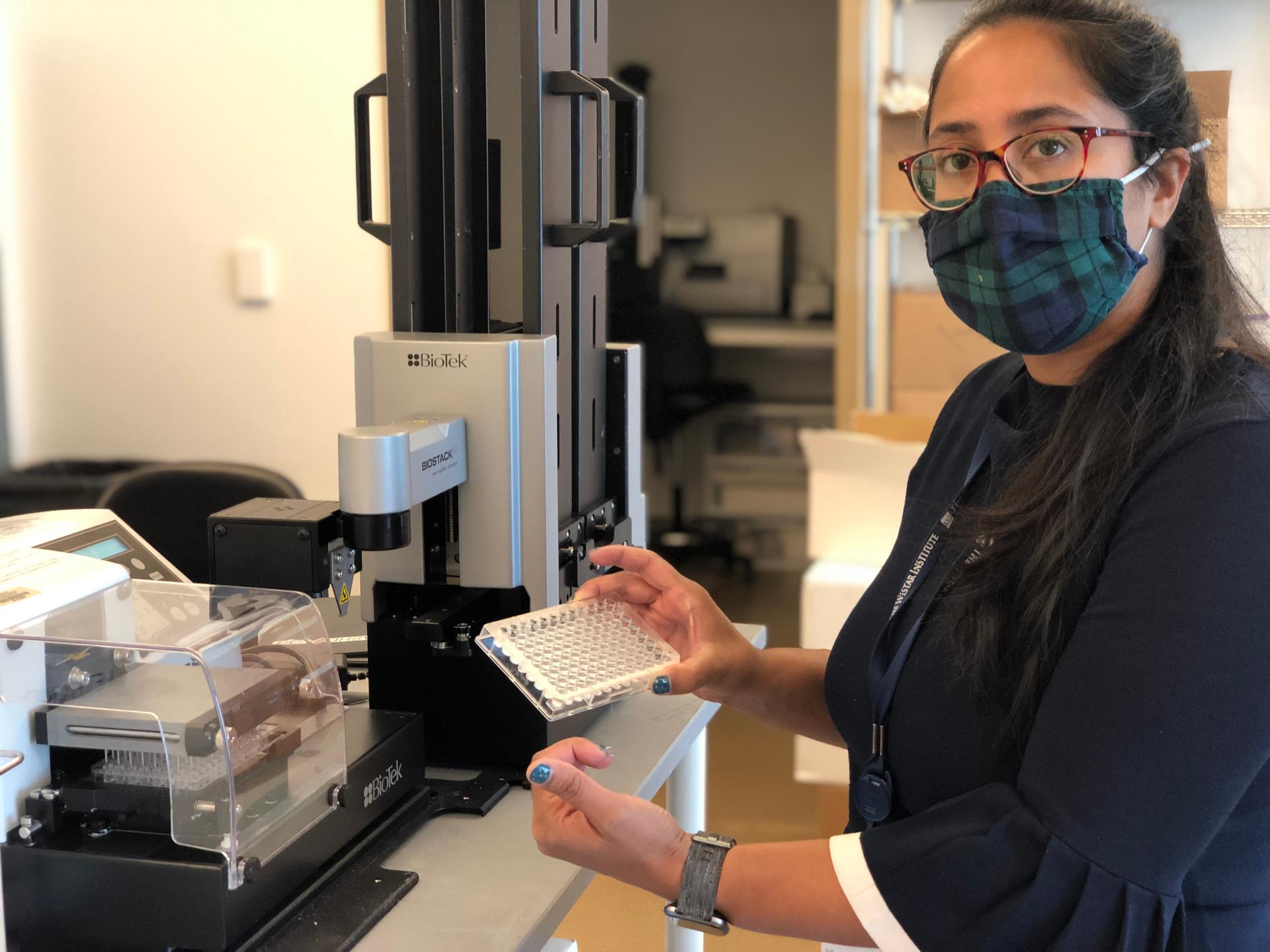

“It just has that little blueprint of the virus, that little sequence, so that it tells your body to make an immune response against this, so that it can protect you,” said Ami Patel, a scientist at The Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, which is also working on a DNA vaccine for COVID-19 that is in late-stage trials through a Pennsylvania company, Inovio Pharmaceuticals.

Related: Many Venezuelan migrants in Latin America struggle to get vaccinated

DNA is similar to the new class of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19, like those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which have also been in the works for decades, with some key differences.

“The mRNA gets sent to the cells and then it starts translating right away. What happens when you give DNA is that it needs to make RNA first in the cells,” Patel said. “And so, you just have an extra step in the recipe that your cells take care of.”

That extra step in using a DNA molecule brings advantages and disadvantages. DNA is a much more stable molecule compared to mRNA. It’s very easy to make, modify and store.

“Look at the possibilities of vaccinating people in parts of the world where you cannot maintain a cold chain,” Jameel said, adding that he could imagine in the not-too-distant future, “little DNA making machines in doctor’s offices, where you can churn out vaccines,” using codes sent through the internet from across the globe.

“It could completely change the way vaccines are made, manufactured.”

“It could completely change the way vaccines are made, manufactured,” he said.

Why now?

DNA vaccines have already been in use in animals, like horses to protect against the West Nile virus. But for decades, scientists have had a very hard time generating a strong immune response from DNA vaccines in people. Muscle cells in humans really don’t capture and process DNA very well, Jameel said.

One workaround now is that instead of a muscle jab, scientists are figuring out different ways to deposit DNA under the skin. That’s where the right kinds of immune cells can capture the DNA and produce the protein, Jameel said.

Related: Cambodia is now better vaccinated than many US states

Efficacy of 67% is also lower than some other COVID-19 vaccines, like the mRNA ones. Jameel said ZyCoV-D is very good at preventing serious infection, all the while being tested when the highly transmissible delta variant was in full swing.

Even if the aim is for something that is more effective, India’s proof of concept is powerful, according to David Weiner, director of the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center at The Wistar Institute. Technology takes time to develop and translate for people.

Weiner has been pioneering DNA vaccines since the 1990s for diseases such as Ebola, Zika and even cancers. In the time since, he said DNA vaccines have been tested in tens of thousands of people and have been shown to be safe. Now, COVID-19 has given DNA vaccines that extra push to enter the real world.

“That’s a very important accomplishment,” Weiner said of India’s authorization, adding that it represents a building block for future improvements. “I think it sort of establishes that there will be a lot more to come.”

For now, the first big test starts in India — to see how well a DNA vaccine works in the real world.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?