China chases ‘rejuvenation’ with control of tycoons, society

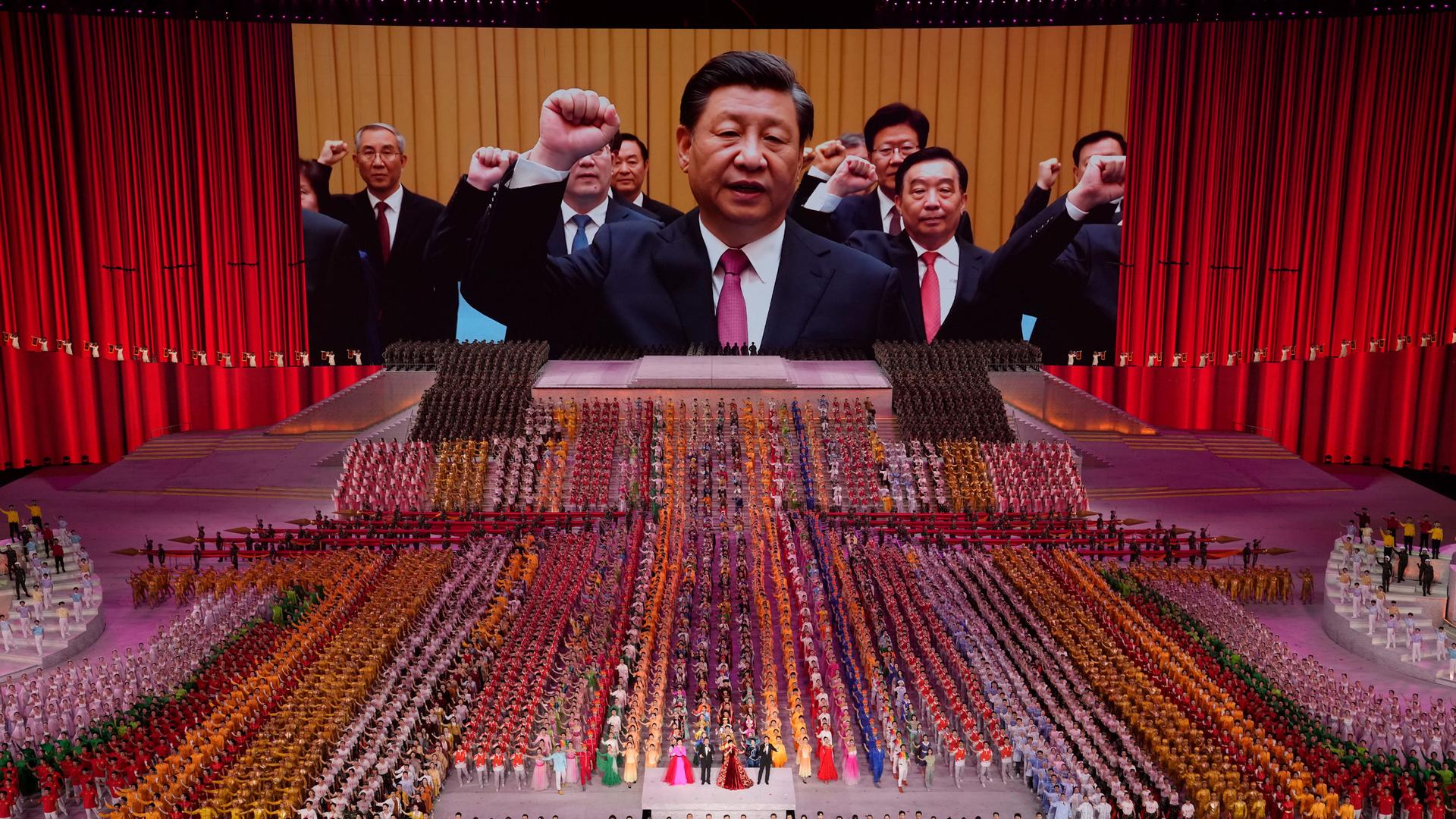

Chinese President Xi Jinping is seen leading other top officials pledging their vows to the party on screen during a gala show ahead of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing, June 28, 2021.

An avalanche of changes launched by China’s ruling Communist Party has jolted everyone from tech billionaires to school kids. Behind them: President Xi Jinping’s vision of making a more powerful, prosperous country by reviving revolutionary ideals, with more economic equality and tighter party control over society and entrepreneurs.

Since taking power in 2012, Xi has called for the party to return to its “original mission” as China’s economic, social and cultural leader and carry out the ” rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation.”

The party has spent the decade since then silencing dissent and tightening political control. Now, after 40 years of growth that transformed China into the world’s factory but left a gulf between a wealthy elite and the poor majority, the party is promising to spread prosperity more evenly and is pressing private companies to pay for social welfare and back Beijing’s ambition to become a global technology competitor.

To support its plans, Xi’s government is trying to create what it deems a more wholesome society by reducing children’s access to online games and banning “sissy men” who are deemed insufficiently masculine from TV.

Chinese leaders want to “direct the constructive energies of all people in one laser-focused direction selected by the party,” Andrew Nathan, a Chinese politics specialist at Columbia University, said in an email.

Beijing has launched anti-monopoly and data security crackdowns to tighten its control over internet giants, including e-commerce platform Alibaba Group and games and social media operator Tencent Holdings Ltd., that looked too big and potentially independent.

In response, their billionaire founders have scrambled to show loyalty by promising to share their wealth under Xi’s vaguely defined “common prosperity” initiative to narrow the income gap in a country with more billionaires than the United States.

Xi has yet to give details, but in a society where every political term is scrutinized for significance, the name revives a 1950s propaganda slogan under Mao Zedong, the founder of the communist government.

Xi is reviving the “utopian ideal” of early communist leaders, said Willy Lam of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “But of course, huge question marks have arisen, because this will hurt the most creative and lucrative parts of the economy.”

Alibaba, Tencent and others have pledged tens of billions of dollars for job creation and social welfare initiatives. They say they will invest in developing processor chips and other technologies cited by Beijing as priorities.

The party’s anti-monopoly enforcement and crackdown on how companies handle information about customers are similar to Western regulation. But the abrupt, heavy-handed way changes have been imposed is prompting warnings that Beijing is threatening innovation and economic growth, which already is declining. Jittery foreign investors have knocked more than $300 billion off Tencent’s stock market value and billions more off other companies.

“I expect that over the next year or two we are likely to see a very rocky relationship develop between the political elite and the business elite,” Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Business, said in a report.

Chinese officials say the public, consumers and entrepreneurs will benefit from higher incomes and more regulatory oversight of corporate giants. Parents welcome curbs announced last month that limit children under 18 to three hours of online games a week and only on weekends and Friday night.

“I feel this is a good rule,” said Li Zhanguo, the father of an 8-year-old boy and a 4-year-old girl in the central city of Zhengzhou. “Games still have some addictive mechanisms. We can’t count on children’s self-control.”

The crackdowns reflect party efforts to control a rapidly evolving society of 1.4 billion people.

Some 1 million members of mostly Muslim ethnic groups have been forced into detention camps in the northwest. Officials deny accusations of abuses including forced abortions and say the camps are for job training and to combat extremism.

A surveillance initiative dubbed Social Credit aims to track every person and company in China and punish violations ranging from dealing with business partners that violate environmental rules to littering.

“Our responsibility is to unite and lead the entire party and people of all ethnic groups, take the baton of history and to work hard to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” Xi said when he and the six other members of the new party Standing Committee appeared in public for the first time in November 2012.

The party Central Committee shifted its economic emphasis “from efficiency to fairness” in late 2020, a researcher at a Beijing think tank wrote in August in Caixin, China’s most prominent business magazine.

The party moved from “early prosperity for some to ‘common prosperity'” and “from capital to labor,” wrote Luo Zhiheng of Yuekai Securities Research Institute. He said leaders are emphasizing science, technology and manufacturing over finance and real estate.

Prominent economists have tried to reassure entrepreneurs.

“It is impossible to achieve common prosperity through ‘robbing the rich and helping the poor,'” the dean of the school of economics at Shanghai’s Fudan University, Zhang Jun, told the news outlet The Paper on Aug. 4.

The 1979 launch of market-style economic reform under then-leader Deng Xiaoping prompted predictions abroad that China would evolve into a more open, possibly even democratic society.

The Communist Party allowed freer movement and encourages internet use for business and education. But leaders reject changes to a one-party dictatorship that copied its political structure from the Soviet Union and watch entrepreneurs closely. Beijing controls all media and tries to limit what China’s public sees online.

As the previous decade’s economic boom fades, “Xi sees himself as the only person capable of recreating the momentum,” said June Teufel Dreyer, a Chinese politics specialist at the University of Miami.

Party members who worry reforms might weaken political control appear to have decided China’s rise is permanent and liberalization is no longer needed, said Edward Friedman, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin.

That means “anti-totalitarian elements of the reform agenda could be rolled back,” Friedman said in an email. “That is what Xi is doing, as manifest in his attack on purportedly gay and girlie culture as a supposed threat to a so-called virile militarism.”

An Aug. 29 commentary by an obscure writer, Li Guangman, described “common prosperity” as a “profound revolution.” Writing on the WeChat message service, Li said financial markets would “no longer be a paradise for capitalists to get rich overnight” and said the party’s next targets might include high housing and health care costs.

The commentary was reposted on prominent state media websites including the ruling party newspaper People’s Daily. That prompted questions about whether Beijing might veer into an ideological campaign with echoes of the violent 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, when some 5 million people were killed.

Hu Xijin, the editor of the Global Times, a newspaper published by People’s Daily that is known for its nationalist tone, responded by criticizing Li’s commentary. Hu warned in a blog post against a return to radicalism.

“The Cultural Revolution was a period of chaos, purposely unleashed by Mao because he felt comfortable in chaos,” Nathan said.

“This is almost the exact opposite,” he said. “It is an effort to create tightly structured orderliness.”

By Joe McDonald/AP