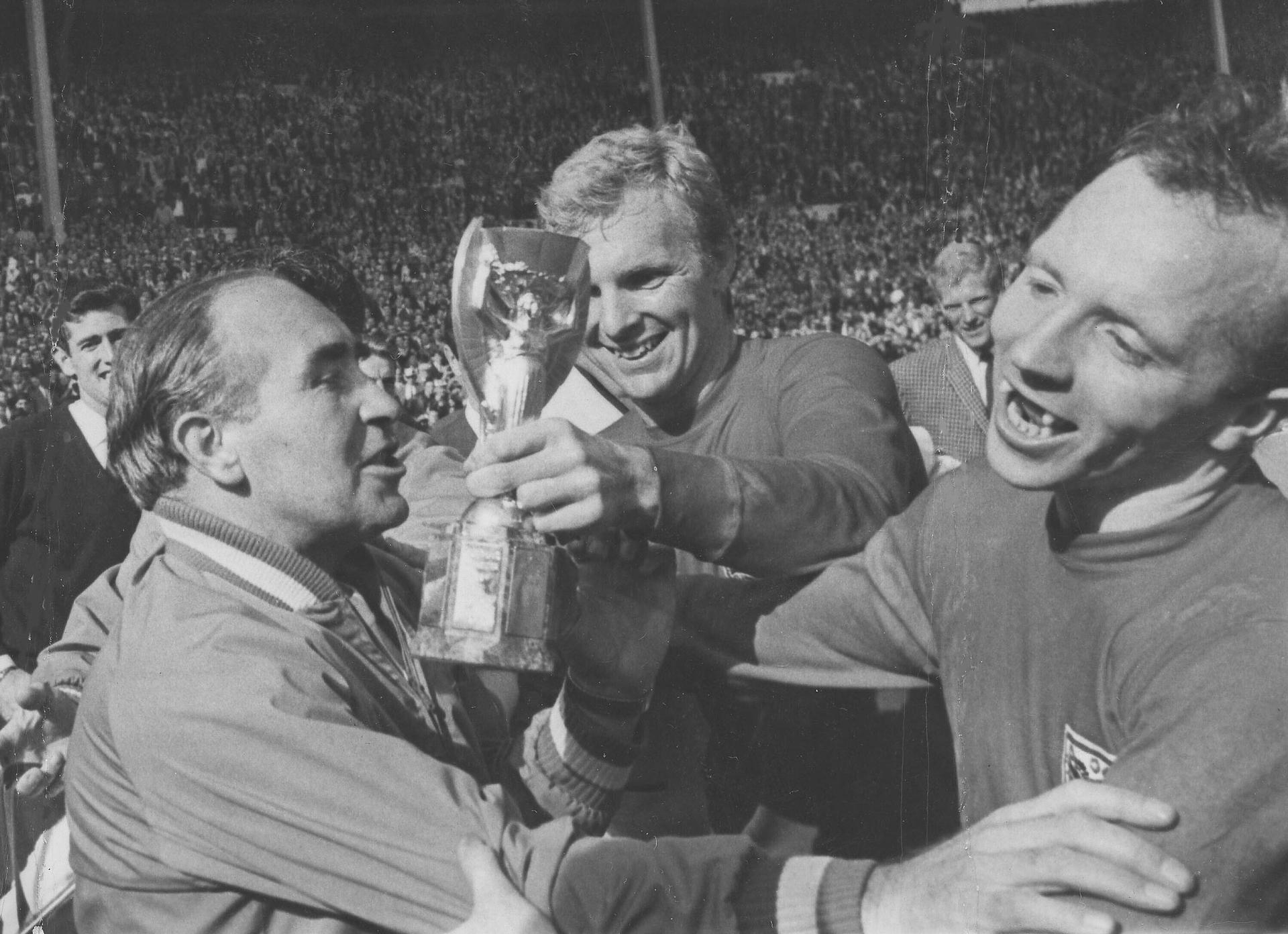

Portugal’s Eusebio, left, and England’s Nobby Stiles have a heading duel for the ball during their World Cup semi-final match at Wembley, London, July 26, 1966. Jose Augusto of Portugal, right, looks on. England won the match by two goals to one.

British comedian John Stiles enjoys watching football matches on TV, but he often winces when he sees the players arch forward and head the ball down the pitch.

Last October, his father, Nobby Stiles, a professional football player, died with advanced dementia. John Stiles believes it was football that caused the brain damage — specifically the thousands of headers Nobby Stiles performed during years of training. (A header is a technique used by players to control the ball using one’s head to pass, shoot or clear.)

Nobby Stiles played with the 1966 England team that won the World Cup — the only time the country ever took home the trophy.

“I worked it out conservatively, I think [Nobby Stiles] would have headed the ball in training over 70,000 times. So, for me, playing the game he loved killed him.”

“I worked it out conservatively, I think he would have headed the ball in training over 70,000 times. So, for me, playing the game he loved killed him,” John Stiles said.

John Stiles’ conviction about the cause of his father’s death led him to donate his father’s brain to science after he died.

Dr. Willie Stewart, a leading neuropathologist at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow, examined the footballer’s brain and found he had extensive chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease that’s linked to repeated blows to the head and seen most often in professional boxers.

John Stiles said his father began to show signs of dementia when he turned 60. First it was his memory that started to go. Gradually, his condition deteriorated until he could no longer swallow food or drink. It was really distressing to witness, Stiles said.

“It was heartbreaking for all of us watching this person that you love disappear so brutally,” he said.

Related: Roger Bennett discusses soccer and his love for the United States

Longer careers, greater risks

Nobby Stiles isn’t the only person from that 1966 World Cup team to develop brain disease. Out of the 11 England footballers who played that day, five were diagnosed with dementia. Four have already died.

Stewart said this is not a coincidence. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 5% to 8% of the population over the age of 60 has some form of dementia. On the 1966 football team, that figure leaps to 46%.

Three years ago, Stewart conducted research into the probability of footballers developing brain disease. His 2019 study found that former professionals were 3.5 times more likely to die with dementia than the general public.

In his latest study, released this month, Stewart examined whether the position footballers play on the pitch and the length of their career impacts their chances of developing dementia. His research found that defenders — who usually head the ball the most — have a five-fold risk of developing neurodegenerative disease.

The longer a player’s career, the greater the risk of brain-related illness, the study also reports.

The findings have led Stewart to call for warning labels to be placed on footballs. A simple message, he said, informing people that heading the ball increases your risk of dementia.

Related: Remembering Diego Maradona, a leftie on the field — and in politics

The neuropathologist argues that other industries include such warnings all the time.

“If there was something in the kitchen which you know would lead to the risk of chopping your hand off, there would be a warning on it. Just because it’s a sport, somehow we seem to bypass these thought processes,” he said.

In 2020, headers were banned for children under 12 during training in England. The Glasgow neuropathologist thinks it’s time to consider banning headers from football altogether.

For those who question whether that’ll ruin the game, Stewart said we need to ask:

“Would you rather we make this change to the game or would you rather continue to see your heroes on the field developing dementia at a very high rate in their retirement?”

“Would you rather we make this change to the game or would you rather continue to see your heroes on the field developing dementia at a very high rate in their retirement?”

New training guidelines

Former professional footballers Gary Lineker and Wayne Rooney have both called for headers to be limited in training or removed altogether.

The English Football Association recently released new guidelines recommending professional players be restricted to 10 “higher-force” headers per week in training.

But Stewart is unimpressed.

“It’s all based on pseudoscientific analysis with figures plucked from the air. Who is going to go around enforcing this? It’s all words,” he said.

But not everyone agrees with Stewart’s concerns.

Premier League footballer Troy Deeney said headers are an integral part of the game and banning them would change the nature of the sport beyond recognition.

The Watford Club captain argued that players need to be able to practice headers during training.

Vincent Gouttebarge, chief medical officer with FIFPro, the International Federation of Professional Footballers, said more evidence is needed to justify banning headers altogether.

“The conclusion that heading will lead to a higher risk of long-term neurodegenerative disease is not valid based on this single study. We need more scientific information about that.”

“The conclusion that heading will lead to a higher risk of long-term neurodegenerative disease is not valid based on this single study. We need more scientific information about that,” he said.

Gouttebarge, also a former professional footballer, said he is more worried about the two concussions he sustained than possible brain injury caused by headers he’s performed during his career.

He also questions whether English FA can impose a ban on headers altogether without the backing of IFAB, the International Football Association Board, that determines the laws of the game. Others worry that a ban on England’s players would put them at a disadvantage against their European counterparts.

An exhausting, ongoing debate

John Stiles finds the continuous debate around the issue exhausting.

He points out that almost 20 years ago, an inquest into the death of former professional footballer Jeff Astle, a striker with West Bromwich Albion, ruled that he died from dementia brought on by repeatedly heading the ball. Little has changed since then, he said.

And Stiles has another reason to be worried. He was a professional player himself for over 10 years with Leeds United and Doncaster Rovers. Stiles said he wasn’t as good a player as his dad, but watching what his father went through has made him anxious. Other former professionals worry too, he adds.

“I speak to other players who are similar [in] age to me — I’m 57. We’re massively concerned. I spoke to an ex-Premier League champion a couple of weeks ago, and he said he was terrified.”

John Stiles believes there’s a class action lawsuit against English FA waiting to happen.

In the US, more than 2,000 former NFL players have lodged dementia claims, although fewer than 600 have received compensation so far.

Stiles said former players and their families feel abandoned by UK football bodies.

“Footballers are treated like cattle. And as soon as they’re no use to the clubs, they don’t see any point in trying to help them, because they’re no use anymore.”

“Footballers are treated like cattle. And as soon as they’re no use to the clubs, they don’t see any point in trying to help them, because they’re no use anymore,” he said.

Related: Police investigate racist abuse of three England players

His family received a little financial help from the professional sports organization, but it only covered around 6% of his father’s medical costs, he said.

“And we only received it because of the World Cup and his profile. Most players don’t win the Cup and most families get nothing.”

Stiles is calling for a fund for footballers and their families to support them, should they develop brain disease. Given what we know today, it’s the very least that English football can do for its players, he said.