‘They want to make the Acropolis into Disneyland.’ Site renovations face backlash.

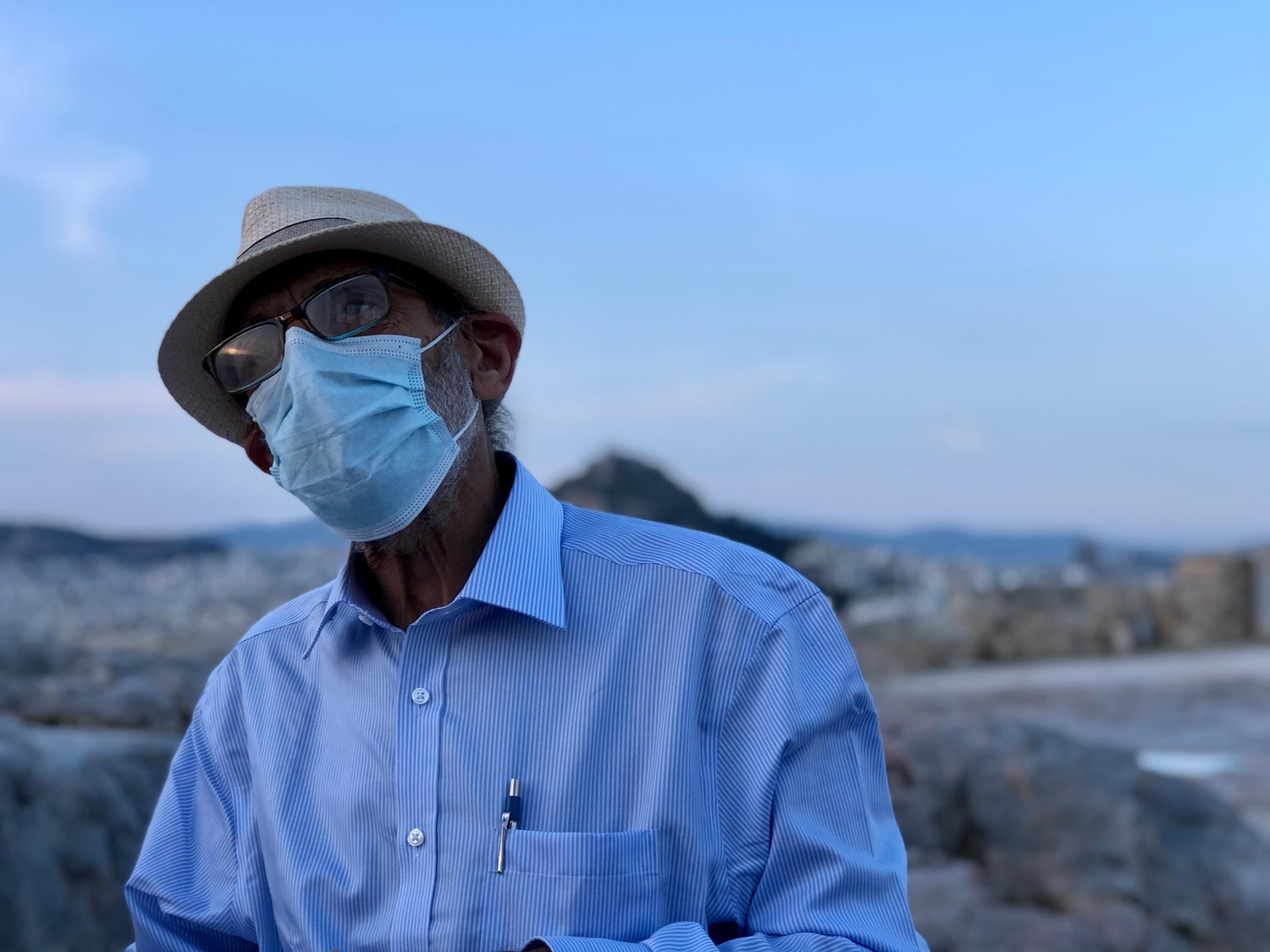

Architect Tasos Tanoulas is intimately familiar with the ancient ruins of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece.

For decades, he led preservation and restoration work on the landmark’s monuments, and on his nearly daily visits, which he’s continued to do even after retiring, he’s encountered a site virtually unaltered.

Related: In Greece, thousands of asylum-seekers are waiting for the COVID-19 vaccine

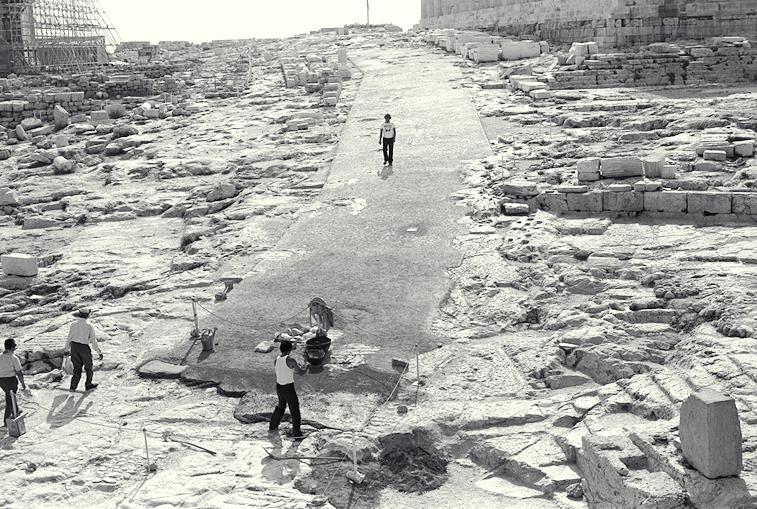

But on a recent trek to the ancient structure, Tanoulas was struck by a change that didn’t require a trained eye to spot: a new concrete walkway being paved around the ancient ruins.

“It was a shock … I was astonished. If … the rest of the archaeological site [is] paved anew, you understand what is going to happen: This is not going to be the Acropolis anymore.”

“It was a shock … I was astonished,” Tanoulas said. “If … the rest of the archaeological site [is] paved anew, you understand what is going to happen: This is not going to be the Acropolis anymore.”

The concrete pathway — a portion of which has since been completed and is expected to be expanded throughout the entire site — is part of an initiative to make the site more accessible to modern-day visitors. Accessibility advocates and Greek officials argue that the project is much-needed and long overdue.

But the plans have also faced fierce opposition from critics in Greece and abroad who say that the already-completed interventions, along with other planned aesthetic changes, threaten to defile the ancient ruins.

The Acropolis, perched on a limestone hill some 250 feet above the Greek capital, is one of the country’s most treasured and often-visited archeological sites, welcoming more than 3 million visitors annually in pre-pandemic times.

Related: As Cyprus’ leaders convene for peace talks in Geneva, some Cypriots say ‘expectations are low’

The UNESCO World Heritage Site houses monuments including the Parthenon — a temple the ancient Athenians built to Athena, the patron goddess of the city, in the fifth century BC.

Despite having the talent, vision and perhaps even foresight to build monuments that captured the imaginations of people for millennia, “the ancient Athenians were not thinking about accessibility,” said Ioannis Vardakastanis, president of the Greek National Confederation of Disabled People (NCDP).

For decades, the Acropolis had not been adequately equipped for visitors in wheelchairs and those with mobility challenges, Vardakastanis said.

During a visit to the site last week, Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports Lina Mendoni said it was unfathomable for the Acropolis, which she likened to “a symbol of Greek … and Western civilization,” not to be accessible to all who wish to visit.

In addition to paving a wheelchair-accessible pathway at the Acropolis, Mendoni said her ministry has also overseen the installation of an elevator, deployment of golf carts to ease transfer from the site’s parking lot and they’re working to make additional changes to the site, such as Braille signs and parking spaces.

The NCDP, which is the country’s leading association for people with disabilities, welcomed the changes and encouraged more to be done.

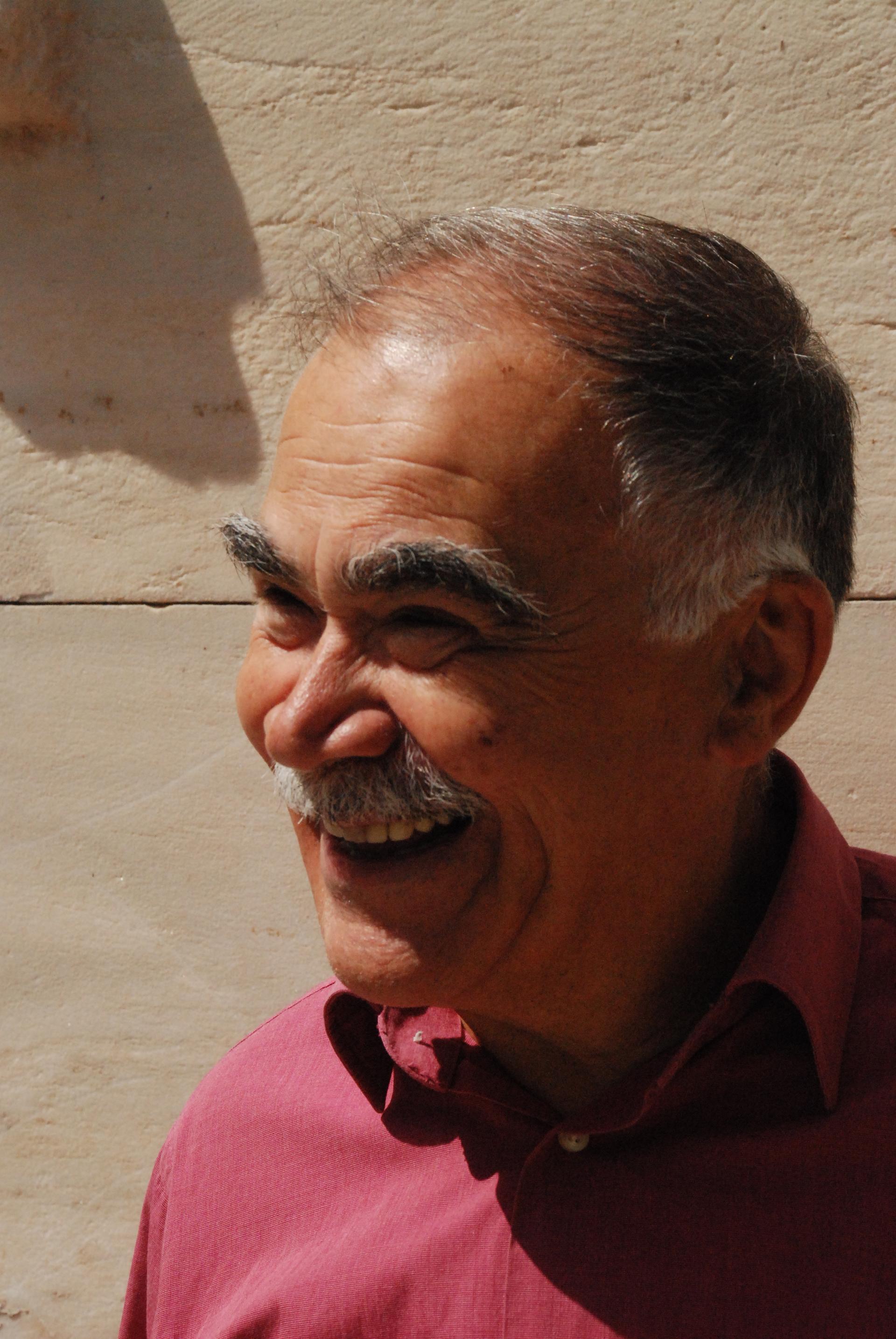

Manolis Korres, an internationally renowned restoration architect and globally respected Acropolis expert spearheading much of the work at the site, said the new pathway, in particular, would improve the experience for all visitors.

“For the first time, visitors will be able to appreciate the monuments” without having to look down and be distracted by worries of falling on the slippery and uneven terrain, he said.

Critics, though, claim the project was carried out without transparency or proper study, and that the reinforced concrete used on the walkway could permanently damage the ancient bedrock underneath — assertions that the Ministry of Culture strongly denies.

The ministry says the renovations were done with utmost respect for the site and after meticulous study, and that the interventions strictly follow internationally accepted principles of reversibility.

More than 600 scholars, artists and other critics have signed a letter aimed at exposing what they see as flaws with the project’s substance and process, and urging that it be stopped.

Critics are also concerned about other interventions that they say go far beyond restoration — and instead would “degrade” and “devalue” the archaeological site. Specifically, they oppose a series of aesthetic changes aimed at restoring the site to what Korres and his team describe as its “correct” and “authentic” form.

The plans include a major overhaul of the ancient staircase leading to the Acropolis entrance and the creation of horizontal terraces that existed on the plateau during the classical period. Korres has also floated the idea of erecting replicas of statues where they once stood thousands of years ago.

“My feeling about all this is that it’s a crime. It’s very sad. It’s like a nightmare to be honest.”

“My feeling about all this is that it’s a crime. It’s very sad. It’s like a nightmare to be honest,” Tanoulas said, adding that he had hoped he would not live to see such changes to the ancient site.

“They want to make the Acropolis [into] Disneyland,” Tanoulas said.

Yannis Hamilakis, a professor of archeology and modern Greek studies at Brown University, has echoed this — and said he finds it troubling that Korres seems intent on reconstructing the Acropolis of a certain moment in history: the classical period.

Related: A mental health crisis on Lesbos is worsening

“This is a site of many different periods. It was very important during prehistory. It was a very important Mycenaean citadel. It was very important in postclassical periods, in Roman times, in medieval times, Byzantine times, during the Ottoman times,” he said.

The renovations, he added, seem to be based on a selective, romanticized, Western fantasy of the Greek, classical period.

“So, in today’s multicultural world, we are building a monument to colonial national ideology of neoclassicism, a monument that does not speak to the realities of the country and of the world, in general,” Hamilakis said.

During his media appearance at the Acropolis last week, Korres dismissed the criticism and rejected the idea that he’s imposing a singular vision for the site.

But he did accept one of the critiques: “We rushed, we had to rush. But look at my age,” the 73-year-old joked while standing in front of the 2,500-year-old Parthenon. “I can’t afford to wait.”