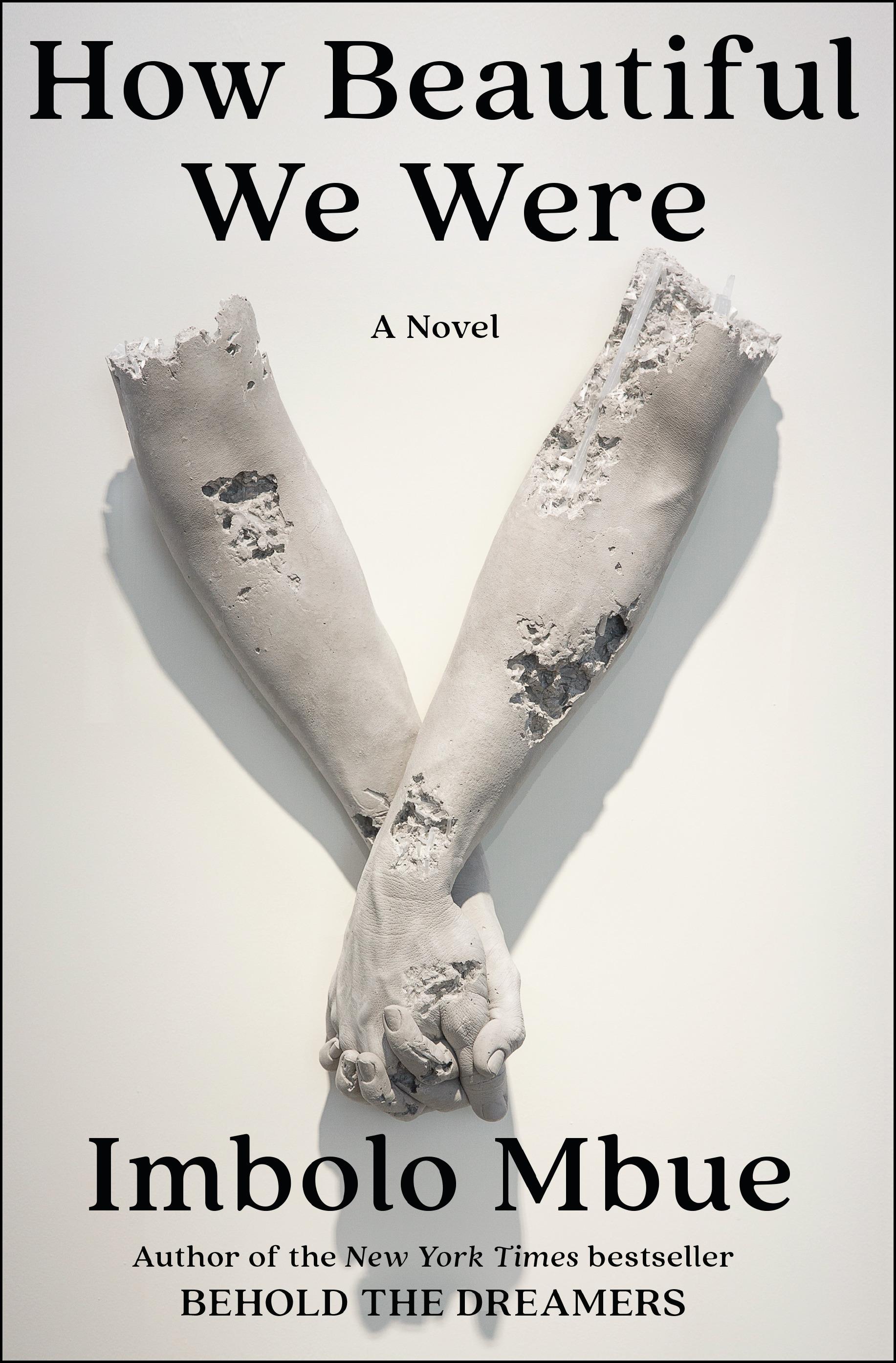

It’s a story of Goliath-versus-Goliath. That’s how Cameroonian author Imbolo Mbue describes her new novel, “How Beautiful We Were.”

Set in the fictional West African village of Kosawa, Mbue tells the story of villagers who stand up to an imagined American oil company that is poisoning their land and water.

Related: Nigerian farmers can sue Shell in UK over pollution

Mbue sat down to talk with The World’s host Marco Werman about what shaped her thinking behind her latest novel and how her characters speak to real-time struggles for environmental justice in Africa.

Related: Big chocolate companies use child labor. Can a 1789 US law hold companies accountable?

The award-winning author says that although the multinational firm wields immense resources, local residents come equipped with their own powers.

Marco Werman: You call “How Beautiful We Were” a Goliath-versus-Goliath story, not a David-versus-Goliath story. Explain what you mean.

Imbolo Mbue: Well, so, this is a story about a small, African village fighting an American oil company, a very powerful multinational. And on the surface, it looks like it’s very imbalanced — and it is — this is a powerful corporation. But I think that people need to realize that small African villages also have their own powers. And these villagers’ determination to hold on to their land, their connection to their ancestry, their willingness to risk everything for the sake of preserving their way of life makes them a “Goliath” also.

Again, this is a novel. It’s a fictional corporation in a fictional village. But you did grow up in Limbe, in Cameroon, a coastal town that has an oil factory. How much of this novel is an account of the world you grew up in?

Well, so I grew up in a town with an oil refinery. That’s correct. And even at a very early age, when I was a young girl, I was very aware of the politics of oil. I also grew up in a dictatorship. Cameroon has had the same president for almost 40 years now. So, my whole life, we had the same president — Paul Biya. … I should add that I am also an Anglophone Cameroonian, and most people don’t know that Cameroon is bilingual. Most Cameroonians are French-speaking, and I come from the minority that speaks English. That definitely put us at a disadvantage. So, certainly as a child, I was very uncomfortable with injustice.

So, Thula — she’s the young woman who leads the rebellion. She’s a complex character. She’s a charismatic leader. But in a society like this, where tradition and religion are so important, would you find a firebrand like her? Do they exist?

Well, that is a very good point, Marco, because I have to say that when I started writing this novel, the part of Thula was more of a man. It was actually Thula’s father who was the person that I wanted to write about initially and that is because I grew up in a world where most of the revolutionaries who were celebrated — the firebrands — they were men. I’m talking about growing up in Africa in the ’80s and ’90s, where we were celebrating the likes of Mandela, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, Stephen Biko, and they were all men. So, I didn’t really consider that character to be a woman so much until I actually started thinking about the fact that there are women like Thula out there — we just don’t talk about them as much. Their stories are not written about as much. And I really wanted to explore this life, not just to be a revolutionary, not just to stand up, but to change with the unique pressures that you have to pay as a woman to do such a thing.

Having a charismatic leader like that, leading a rebellion against a big American oil company — is that wishful thinking? A leader, of any gender, who can do this?

Well, that is the wonderful thing about literature, I suppose. You know, it allows us to dream. Without giving away the story … we have rebellion. It was important to me that I be honest in the way I portrayed everything, that even though these villagers, they wanted to fight against this American oil company, even though they had such passion, it was important that I show how lopsided it was and how much not only the American oil company was against it, but also their own government. And even some people in the community were not exactly in support of the struggle.

I do think that there are lots of Thulas in the world. I’ve read a lot about women, especially in Latin America, who were fighting against environmental destruction of their lands. So, it wasn’t exactly a case of being wishful that this can happen. It was more about portraying honestly the lives of people who would choose to risk so much for justice.

We’ve actually been covering the recent ruling that allows Nigerians to sue Shell Oil in Britain over oil spills. There’s a similar ruling in a court in the Netherlands. What do you make of that news? Will it make a difference in Cameroon?

Yes, I was so happy when I heard it. And part of this story came from that need to understand why more wasn’t being done to push back — to make these companies realize that you can’t just destroy people’s lands because you want to get their oil. And I mean, part of my novel was inspired by a great Nigerian activist named Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was murdered by the Nigerian government at the time because he stood up against Shell and he was hanged to death.

Ken Saro-Wiwa likely inspired people like Nnimmo Bassey, an environmental justice activist in Benin City, Nigeria, who we spoke to recently about the ruling in the UK. He was pretty excited by what it means but says it’s not going to change life on the ground there.

There’s been so much pollution, so much degradation in the environment that you can’t exactly hope that “OK, we’re going to take this money and just clean the waters and then we can start eating the fish.” You know, I am uncomfortable with the idea that Africans cannot get justice in their own country. They have to go to foreign courts to get justice, even though Western corporations come and destroy land over there, we have to go to court in The Hague, or the UK, to get the corporations to give us justice.

The motives of the villagers in this book who take on big oil — they’re not pure motives or one-dimensional. What do you think the nuances are of this big oil company versus small-village-with-lots-to-gain narrative? What do you think outsiders don’t really appreciate about that?

We are all human, right? African villagers are humans and the people who work in corporations are human. So, it was important to me to not just portray a story of, you know, oh, “These wonderful African villagers, they’re being treated poorly and they’re such good people and they have this noble fight,” because, yes, they did have a reason to fight, but they also had their own flaws. Thula had her flaws, like you mentioned earlier. The village head is … — we don’t even know which side he’s on. And there are many people who make poor choices. And at one point, without giving away too much, there is a use of violence. So, I wanted to think about what it’s like to be human and to be flawed and to be fighting for justice and to put all of your flaws within that struggle.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?