This essay is part of “On China’s New Silk Road,” a podcast by the Global Reporting Centre that tracks China’s global ambitions. Over nine episodes, Mary Kay Magistad, a former China correspondent for The World, partners with local journalists on five continents to uncover the effects of the most sweeping global infrastructure initiative in history.

As winter arrives high up in the Himalayas, troops from Asia’s two giants remain in a tense standoff at their long-contested border, where India and China fought a war in 1962, and then faced off again just months ago. Now the two sides are in talks to deescalate the situation, with a plan on the table to pull back military forces.

In hand-to-hand combat around May, Indian and Chinese troops beat each other with sticks and stones — before better-armed soldiers arrived in June. Despite the long-standing agreement not to use gunfire on the non-demarcated Line of Actual Control (LAC) border, at least 20 Indian troops and an undisclosed number of Chinese soldiers died in the clashes.

The confrontation also signaled a sharp turn for the worse in India’s and China’s relationship, which had somewhat warmed over the past dozen years, with China becoming one of India’s top trading partners. Chinese companies have helped to build and supply subway lines in India’s cities, with hopes in some quarters that India will be able to further engage China’s experienced construction companies to overhaul aging Indian infrastructure.

“We can’t build enough bridges or we can’t modernize our railways fast enough. So, all of those skills, actually the Chinese have.”

“We have an infrastructure deficit,” said Santosh Pai, a partner with Link Legal in New Delhi. Pai lived in China for years and now advises both Chinese companies who want to invest in India and Indian companies seeking to invest in China.

“We can’t get our roads built fast enough,” said Pai. “We can’t build enough bridges or we can’t modernize our railways fast enough. So, all of those skills, actually the Chinese have.”

Related: Opening the door to Chinese investment comes with risks for Southeast Asian nations

China’s telecommunications companies were among those that installed 3G and 4G systems in India. And until the June border clash, Huawei was under consideration to install 5G. Their involvement may now be off the table, and India — not unlike the US — has also banned dozens of Chinese apps, including TikTok, citing security concerns.

China’s critics in India consider the prospect of Beijing controlling Delhi’s 5G networks to be potentially most worrying.

“The fear is that they have source code of these technologies and they can manipulate it to their advantage in a critical situation,” says VK Cherian, a telecommunications consultant in New Delhi. “Or they can literally shut off some networks — critical networks.”

India’s leaders have also resisted China’s efforts to pull India into other sorts of networks that China leads or dominates. That goes for the new free-trade deal, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Agreement (RCEP), which was signed Nov. 15, and brings together most East Asian countries that represent almost a third of the global economy. And it goes for China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

‘Our sovereign territory’

Even before border tensions ramped up, Indian strategists had become increasingly wary of China’s regional and global ambitions — with a Chinese presence now firmly entrenched in deep-water ports to India’s east in Myanmar, to its south in Sri Lanka, and to its west in Pakistan.

India has opted not to join China’s BRI, which is a massive project to finance and build roads, railways, ports, pipelines, 5G and other infrastructure in dozens of countries around the world. The objective is to solidify a new network of global trade and power with China at its center.

Related: The ‘China dream’: New Silk Road begins at home

Many Indians — and other Asians — would prefer a region that’s networked in multiple directions — and not dominated by China. That’s one reason India hasn’t joined the BRI or RCEP.

India also has a more immediate reason for keeping its distance from China’s Belt and Road endeavors. One of the BRI’s signature projects, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), runs through Pakistan-administered Kashmir, which India sees as its sovereign territory, unlawfully occupied by Pakistan soon after British colonialism ended in 1947. That was when the British separated the Indian subcontinent into two nations: India, a majority Hindu country, and Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country.

The area where Chinese and Indian troops are now at loggerheads is the Ladakh area in the greater Kashmir region. Chinese troops seized territory there in the 1962 war and in the more recent summer skirmish. And China claims more territory that India now controls.

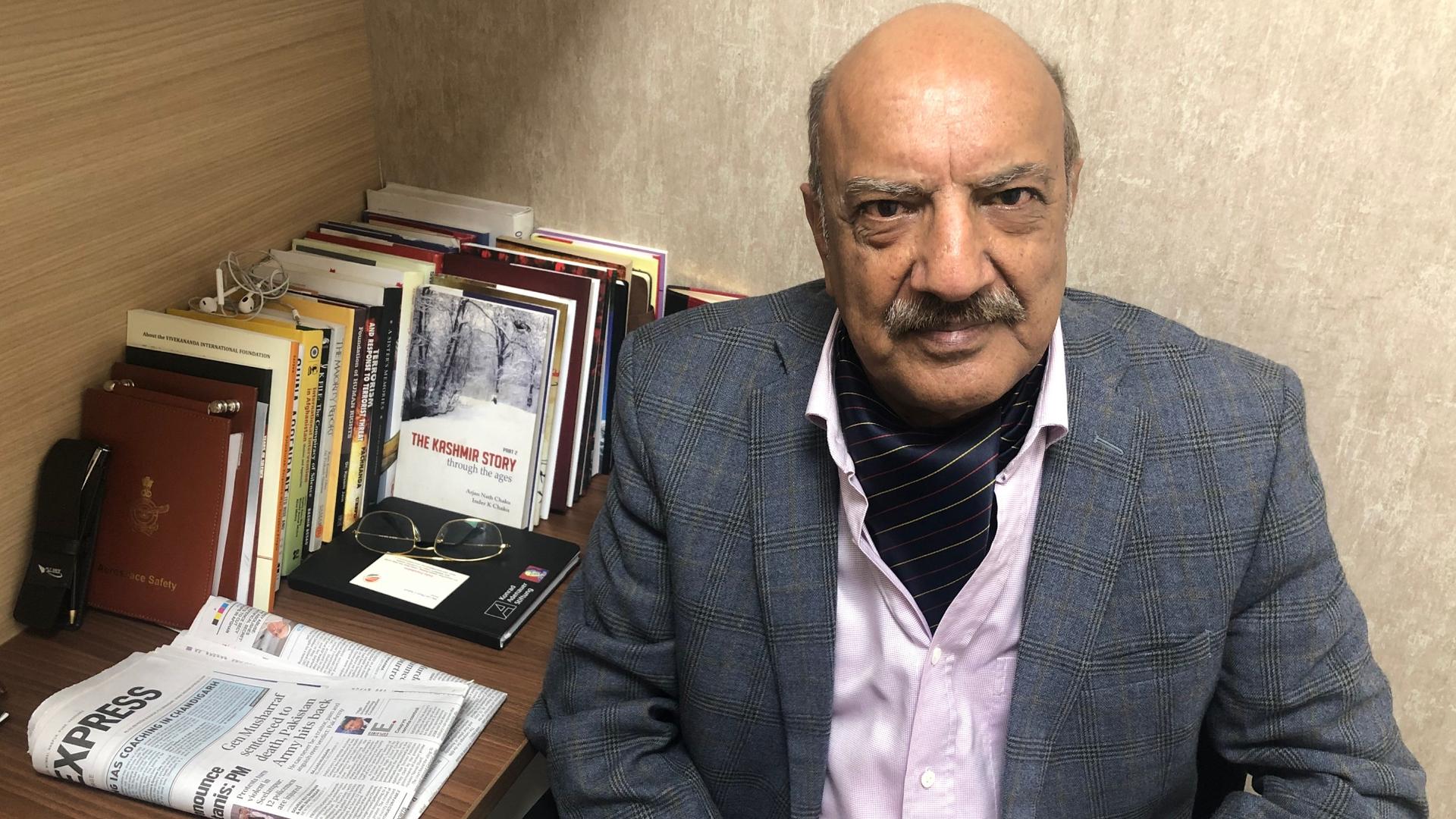

“So far as India is concerned, there is no way we can ever support the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. It passes through our sovereign territory,” says Dhruv Katoch, a retired major-general in the Indian army who spent much of his career defending Indian sovereignty in Kashmir.

Katoch has also directed India’s Center for Land Warfare Studies, the Indian army’s premier think tank. He argues that India needs to be alert about China’s Belt and Road activities in Pakistan, including the construction of dams, a railway and a road that will run from China, through Kashmir, diagonally southwest across the country, to Pakistan’s strategically-located port of Gwadar.

Gwadar is near the Iranian border and not far from the Strait of Hormuz, which leads to the Persian Gulf. Around one-quarter of the world’s oil passes through there, as do US naval ships, coming and going from their base in Bahrain.

China’s BRI includes big expansion plans for the Gwadar port. The development encompasses industrial parks and new housing for Chinese workers. The vision is consistent with a Chinese strategy called “port-park-city,” which promotes urban growth starting with port facilities and then continuing with other infrastructure. The term also is associated with the idea that China can build for predominantly civilian use now but pivot toward potential military use later.

‘Very major security concern’

Katoch is troubled by the road passing from China through contested Kashmir to Gwadar.

“I think it is a very major security concern,” Katoch says. “To protect that road, a very large number of Pakistani military troops are employed. But what is not known is that a very large number of Chinese soldiers are also employed.”

“These soldiers are not in uniform, but they are part of the security apparatus of the Chinese state,” he added. “And I think it gives China and Pakistan a nexus to join hands from this particular area should any hostilities take place between India and China.”

Isfandiyar Pataudi, a Pakistani retired major-general who was once up for consideration to head Pakistan’s premier military intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), disputes that any armed Chinese are operating in Pakistan.

“No foreigner can carry a weapon in Pakistan, including Chinese,” he says. “That’s the rule. And so this fear — American audiences need to dispel — that there is going to be a Chinese outpost at the mouth of the Persian Gulf.”

Gwadar has more challenges than most BRI ports. It’s in Balochistan, one of Pakistan’s poorest provinces. Over the years, it’s seen outsiders come in to mine copper and gold and drill for oil, leaving little benefit for ethnic Baloch people.

Now, with China’s presence, the separatist Baloch Liberation Army has pushed back with repeated attacks on Chinese workers, on a luxury hotel in Gwadar, and on the Chinese consulate in Karachi. But still, Chinese construction continues.

“I think China’s had its eyes on Gwadar Port for a very long time,” says Taha Siddiqui, a Pakistani journalist who long covered Balochistan. “And it’s going to get that no matter what, and keep that, no matter what.”