As the United States confronts its long history of racial injustice, powerful environmental groups like the Sierra Club are coming to grips with their own history of racism and white supremacy.

The national environmental movement in the United States is still dominated by white voices and often excludes people of color. The environmental justice movement, which is typically community-based and more often driven by people of color, is frequently an afterthought among large green organizations and the foundations who fund them.

Washington Post environment reporter Darryl Fears has written for a number of years about the lack of diversity among large green organizations, so he is not surprised that these problems persist.

“Everywhere I went, there were hardly any other people but white people in the room, and it was stark.”

“Everywhere I went, there were hardly any other people but white people in the room, and it was stark,” Fears says. “And after three years of reporting, I asked, ‘Why is that?’ White people aren’t the only people who are impacted by pollution and climate, and white people aren’t the only people who care about the environment.”

Related: A global push for racial justice in the climate movement

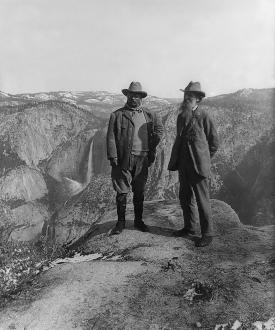

Fears says he started probing this question and spoke with many people at these groups. “That’s when I personally began to learn about the history,” he says. “I already knew about Teddy Roosevelt. But I didn’t know about John Muir’s connection to white supremacy and white supremacists, and I didn’t know about Madison Grant and others. And that began my education about the origin of these groups.”

John Muir is the founder of the Sierra Club and a legend in the environmental movement. He is known as “the father of national parks” because he fought to preserve vast areas of land, including Yosemite National Park and what is Sequoia National Park.

Recently, however, Michael Brune, Sierra Club’s executive director, issued a public statement apologizing for the organization’s role in “perpetuating white supremacy” and apologizing “for all the harms the Sierra Club has caused and continues to cause, to Black people, Indigenous people and other people of color.”

“And then he took it a step further,” Fears adds, “and said, not only do we recognize that Black lives matter and this racial reckoning needs to happen in the United States, but we’re going to look at the past of the Sierra Club, which was fraught with racial history, and at its founder, John Muir, who said some pretty disparaging things about people of color, including African Americans and American Indians.”

Fears thinks it’s interesting that 20 years into the new millennium, these organizations suddenly feel a need to come clean about their white supremacist roots.

“You’re talking about Madison Grant, who wrote ‘The Passing of The Great Race,’ or the ‘Racist Basis of European History,’ which Adolf Hitler, before he became the leader of Nazi Germany, called his bible,” Fears notes. “And Joseph LeConte and David Starr Jordan — people who believed in eugenics and…that inferior people should not be allowed to breed, [that] they should be sterilized for the preservation of whiteness so that there will always be more white people than non-white people in the United States.”

In the US, the overwhelming whiteness in the environmental movement exists primarily at the national level. At the local level, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans generally separate themselves into another category, which is the environmental justice movement, Fears says.

“These groups work in the shadow of the big green groups, and in the shadows, obviously, of the foundations that give money to these green groups…”

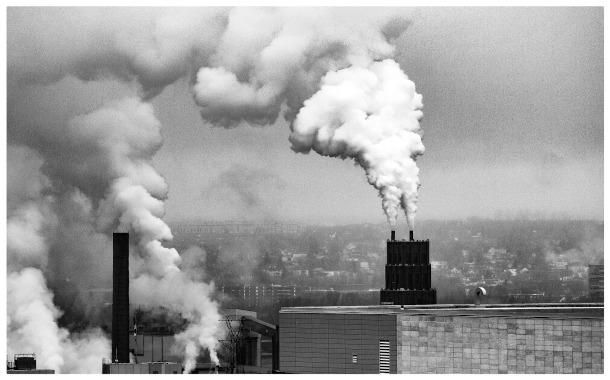

“These groups work in the shadow of the big green groups, and in the shadows, obviously, of the foundations that give money to these green groups,” he explains. “They work in impoverished communities and they work in poverty themselves. They are barely funded and they do the work required to keep power plants that pollute the air away from these people or to keep them honest, as much as they can.”

Related: Quest for racial justice in US must include environmental and climate issues, activists say

Other groups, such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, are also confronting their failure to diversify and to treat the non-white workers in their ranks with respect and dignity.

Recently, a woman named Ruth Tyson, a Jamaican immigrant who worked at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), wrote a 17-page email detailing her difficult experiences within the organization.

“She describes the white people, or her white co-workers, as fairly cold and not very communicative with her,” Fears says. “Her work is criticized. Her ideas are dismissed. Three black women who were on her team were forced out or quit because of the treatment they received.”

When Fears read her email, he was sure that the UCS would say “some of this is unfair.” To his surprise, when he contacted the president of the organization, he said he was “very concerned and heartbroken that she found her treatment at the organization so unfair,” Fears says.

“I thought that was remarkable,” he adds. “In fact, as a journalist who’s used to tension in these interviews and a give and take, I was kind of thrown off balance by his total agreement with her.”

Tyson sent her letter to 200 people at the UCS, who then forwarded it to “basically the entire conservation field,” Fears says.

“And when I talked to the leaders at organizations, they had not only read it but they, too, agreed,” he explains. “They said that her words rang true about what they’ve been told by the non-white staff at their organizations. Michael Brune said that he found it heartbreaking and that it aligned with the criticism that he heard at the Sierra Club.”

Over the last decade or so, Fears says, the big green groups have done a “very poor job of changing themselves” to reflect the changing demographics in the US. By 2050, he notes, people of color will be a majority in the United States, “so these green groups will have to change a great deal to represent a majority of the people in the United States over those 30 years.”

Fears understands that these organizations are fighting high-stakes issues: climate disruption, the loss of tropical rainforest, pollution, a severe public health crisis and others, all of which disproportionately affect Black, Indigenous and other people of color more than white people in the US.

“These groups do great work,” Fears notes. “They do the work to protect the environment, they do try and serve their mission as best they can. But at the same time, these groups have felt that they haven’t really reached out to Black and brown communities the way they should for at least a decade, and in the decade since acknowledging that, they’ve done very little.”

This article is based on an interview by Steve Curwood that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.