For this Latina artist in New York, goodbye to all that Goya

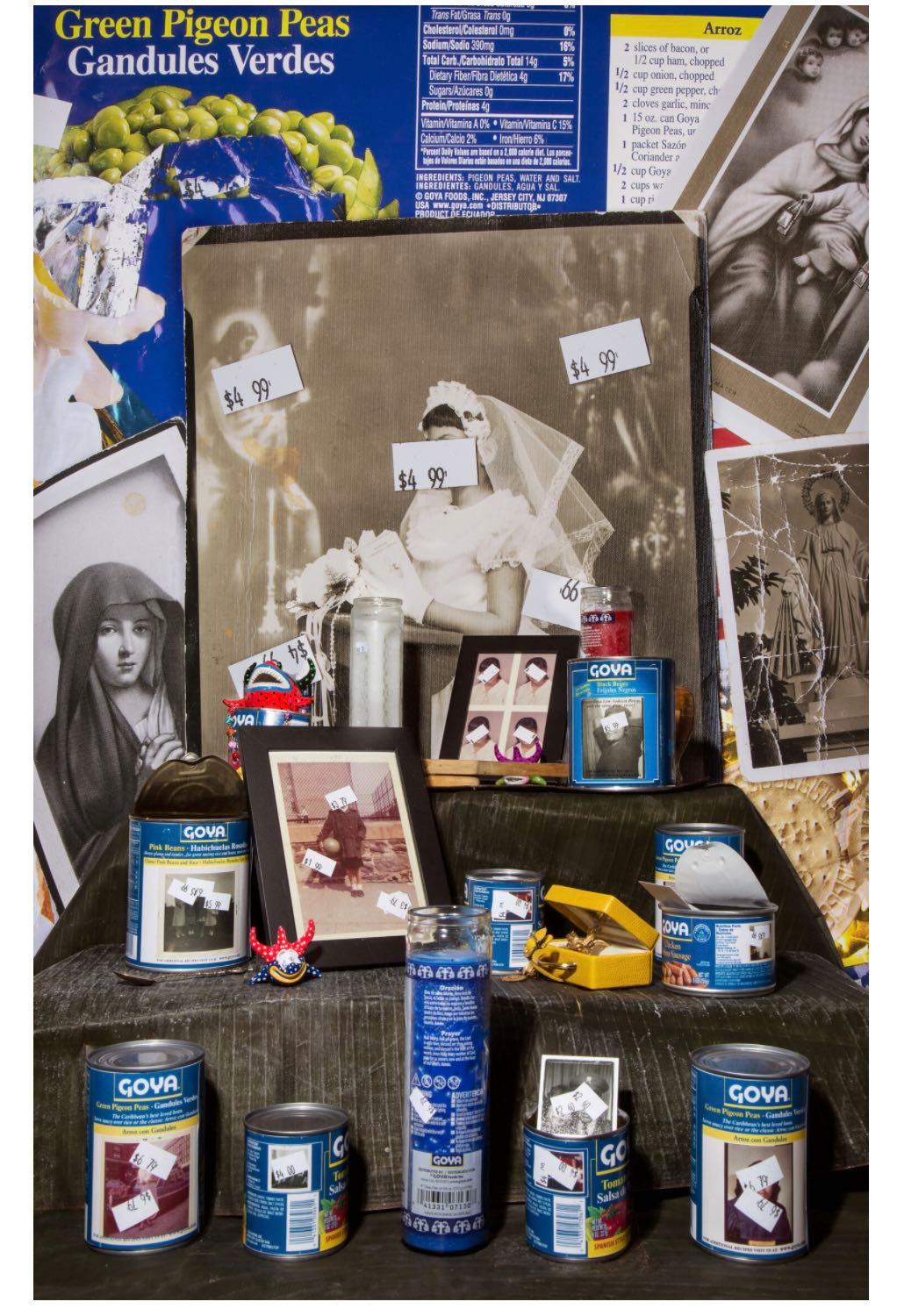

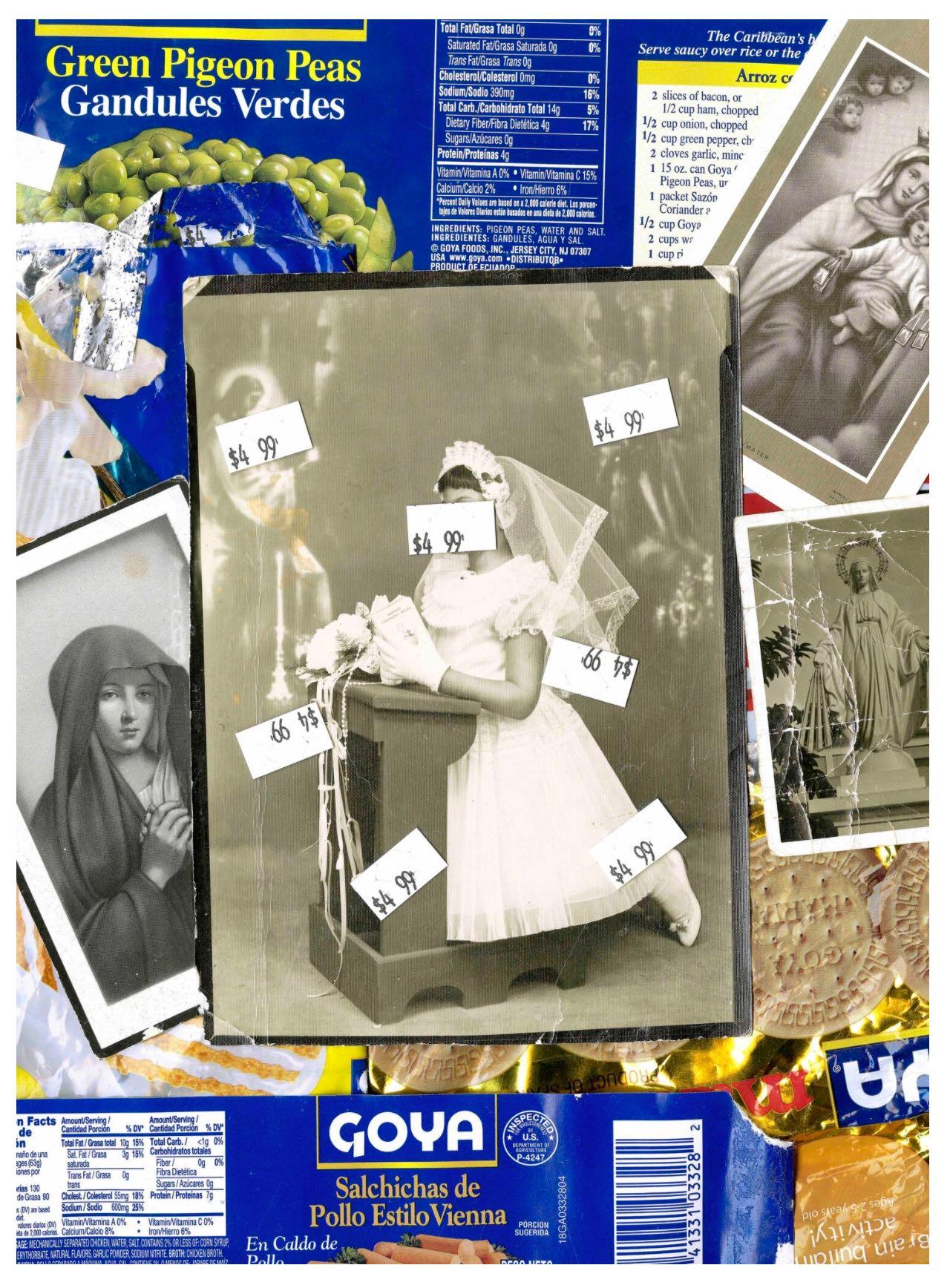

At first glance, Puerto Rican artist Ysabel Turner’s photography exhibit, “Tiene Que Ser Bueno,” or “It Has to be Good,” looks like a colorfully adorned shrine to the Goya brand, with canned vegetables and Goya prayer candles laid out on an altar of banana leaves.

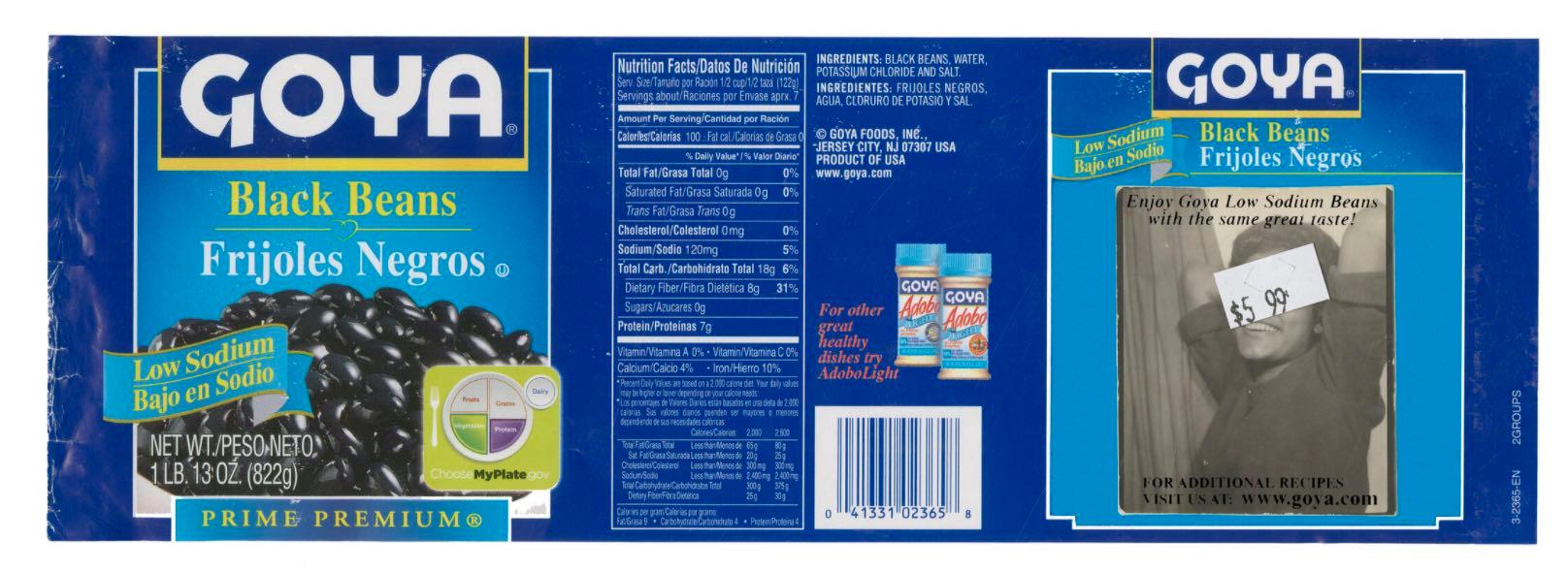

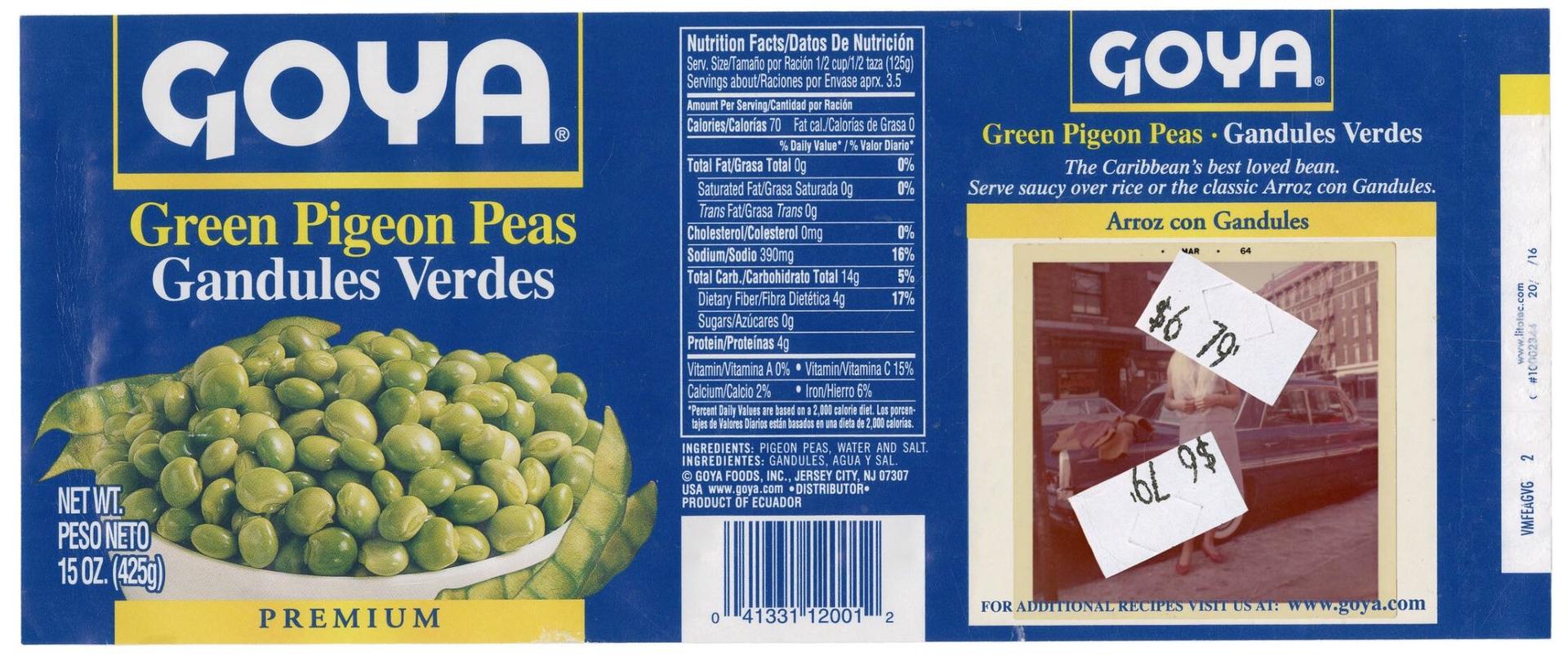

Old, archival photographs are camouflaged into the display. Turner overlaid and reprinted all the Goya cans’ ingredient labels with her family’s photographs. Small white price tags cover the faces of each family member.

Turner grew up in a Puerto Rican household where Goya was not just a pantry staple, but a means to make dishes that felt like home. For many Latinx and Caribbean households, dishes typically made from Goya products, such as mofongo and arroz con gandules, connect the diaspora to the homeland. Growing up, Turner felt like Goya was part of her Puerto Rican identity.

“A lot of it is intertwined with … memory of family and togetherness, funerals, weddings,” Turner said. “I think of Puerto Rico, my grandma.”

But that has changed in recent years as Goya’s politics have come under scrutiny. The hashtags #Goyaway and #BoycottGoya trended on Twitter recently after the company’s chief executive effusively praised US President Donald Trump at the White House last week.

The CEO’s comment alienated many loyal Goya consumers who have felt targeted by the Trump administration’s anti-immigration rhetoric and policies.

Turner said the recent calls for a Goya boycott from prominent leaders in the Latinx community, including Rep. Aexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and former Democratic presidential candidate Julián Castro, echo the outrage she and others have felt about Goya in the past. Now, she urges people not to stop there, but to go deeper into thinking about food and identity.

“I feel like rebuilding an identity through food and decolonizing culture starts with things you buy … But don’t just jump to the next Spanish food brand; look into what they post on their website. Who are they?”

Turner says she realized that she needed to divorce her Puerto Rican identity from Goya years ago. And she used her series to do just that. Her exhibit was shown at the New York City Aperture Foundation in 2018. Today, the images can be seen on her website.

Turner’s relationship with Goya changed after the 2017 Puerto Rican Day Parade in New York City. That year, Goya ended its 60-year relationship with the parade, pulling its sponsorship after event organizers decided to honor the Puerto Rican activist and revolutionary Oscar López Rivera. Rivera was a leader of the militant group called the Armed Forces of National Liberation.

Many Puerto Ricans see him as a freedom fighter, while others consider him a terrorist. Goya’s decision to pull out of the parade sparked a contentious debate in the Latinx community; many were outraged over the side the company seemed to take in Puerto Rican liberation.

Related: New York’s Puerto Rican Day Parade stirs tensions about statehood

That led Turner to reflect on her own relationship with Goya and to ask herself: If Goya wasn’t for Puerto Ricans, who was it for? Why, she wondered, had Goya become a symbol, a representation, of Latinx identity?

“I think what sparked that was me thinking about my own family,” she said. “Who was behind these products, whose cultures have been boiled down to fit into these packaged goods?”

Related: Trump, Biden boost efforts to reach Texas Latino voters

In her search for an answer, she began experimenting with overlaying her photos onto the labels of Goya cans. This experiment turned into an entire series, which she named for one of Goya’s most popular marketing slogans: “Tiene Que Ser Bueno,” or “It Has to be Good.”

Turner was struck by how much Goya pushes the idea of achieving the American dream through consuming its products. The company even states this mission on its website.

But the way Turner sees it, Puerto Ricans have never been granted the American dream. And Goya, she felt, never really cared about the relentless hardships the Puerto Rican community has faced.

“It was also a death or a goodbye to Goya,” she said. “A goodbye to that chapter of them being my iconic symbol for my culture.”

Related: Banksy unveils new pandemic-inspired art featuring rats in face masks

For Turner, letting go of Goya didn’t have to mean letting go of the food that connects her to Puerto Rico or her family memories.

“I don’t think you have to lose your culture or … the flavors,” Turner shared after thinking about how she’s continued to rebuild her Puerto Rican identity through authentic foods, like her mother’s homemade sofrito recipe. “Because once upon a time, there wasn’t a Goya.”