After years apart, this Syrian doctor in New York is finally celebrating Ramadan with his family

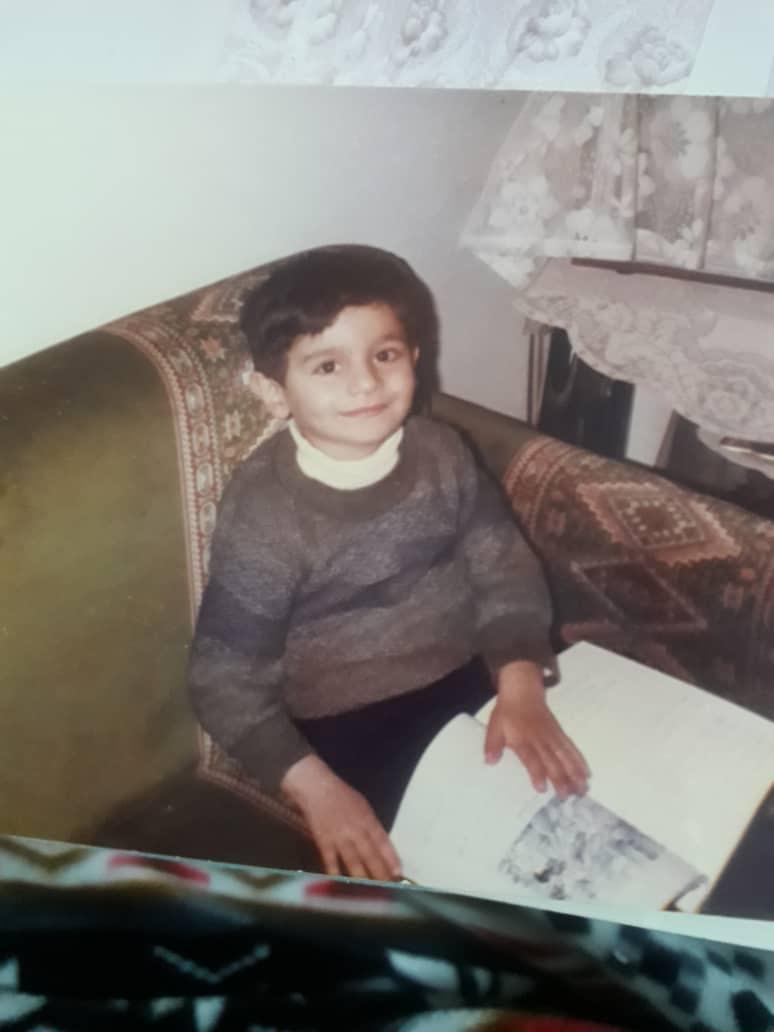

Rami grew up in Syria in the 1980s, in the city of Homs. As a boy, he remembers how Ramadan — a monthlong observance marked by Muslims the world over by prayer, daily fasting and acts of charity — was a centerpiece of life.

“When you go out, you see no cars in the streets, all the stores are closed, all the people are with families. So, we gather as a family, my father, my brother, my sisters. We eat, we watch TV a little bit, then go to the mosque.”

“When you go out, you see no cars in the streets, all the stores are closed, all the people are with families,” said Rami, now a doctor doing a residency in New York. “So, we gather as a family, my father, my brother, my sisters. We eat, we watch TV a little bit, then go to the mosque.”

Related: Under lockdown, mosques in Kenya offer virtual prayers for Ramadan

Those memories have carried him through many a Ramadan; his work has meant long separations from his family both in the Middle East and the US, leaving him alone during the holy month.

Saturday evening marks the end of Ramadan. But this year, even though Rami is putting in long hours treating patients with the coronavirus, he’s thankful for a more traditional celebration of Ramadan — with his wife Shaza, and their young son. (Their full names aren’t being used to protect their families back in Syria.)

Early on, Rami gravitated toward science and medicine. But to become a doctor, Rami had to leave his family behind in Homs, first for medical school in Damascus, and then for his OB-GYN residency in Aleppo. He was a natural. Some families even named the babies he delivered after him.

But medication and equipment shortages made the work difficult. Rami and his team searched for alternatives. Multiple times, he performed a cesarean section using the light from his cellphone. A lack of machines like incubators meant babies sometimes died needlessly.

After his residency, Rami returned to Homs and fell in love with Shaza, who would become his wife.

“He was very funny,” Shaza recalled, “and I liked his honesty and determination to be a doctor.”

Related: Study tracks growing list of COVID-19 symptoms in real-time

Rami was finally back home with family. But by this time, in 2012, Syria was slipping into civil war. Rami says the government of Bashar al-Assad did not permit his patients to go to the hospital, so they had to sneak out to have their babies delivered. Practicing medicine in Syria became increasingly difficult. A month after celebrating Ramadan at home with his family that year, Rami once again relocated.

“When you finish your studying, you have to go to the army,” he said. “I didn’t want to serve that army, so I moved to Jordan.”

He was on his own. He continued to treat many Syrian refugees in Jordan, and the days were long. During Ramadan, it seemed to him that women timed their births to coincide with the day’s breakfast, he said with a smile. So, he would drink water, deliver the baby, and then, an hour late, break his fast in the on-call room of the hospital with other doctors and nurses. They would eat simple things, like chicken and rice.

Rami and Shaza married but lived apart. And still, practicing medicine was filled with obstacles. The field hospital where he worked in Jordan lacked resources, so C-sections and blood transfusions were out of the question. In late 2013, Rami got a visa to come to the United States, to New York.

Related: How coronavirus is changing the way Muslims celebrate Ramadan

“When I came to the United States,” he said, “I applied to increase my experience. I want to be a doctor here. I want to be exposed to new fields.”

Rami eventually landed a job as an attending physician at Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center in Brooklyn. But Shaza’s visa applications kept getting denied, so they continued to live apart. They would Skype for hours. They’d talk, eat, study and even sleep with Skype open.

For seven Ramadans in a row in the US, Rami was on his own, far from home.

“The most challenging thing was eating alone because this is the time when the family gather and eat together, having fun. But for me, for seven years, I didn’t have this opportunity.”

“The most challenging thing was eating alone,” he recalled, “because this is the time when the family gather and eat together, having fun. But for me, for seven years, I didn’t have this opportunity.”

Related: Wajahat Ali on maintaining one’s faith through crises

Finally, Shaza got her visa and joined Rami in the US earlier this year. And just two months later, their son, Kosai, was born.

“I think God helped me,” Rami said. “Everything came together.”

Today, Rami is an attending physician at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn. Of late, he has been treating patients with COVID-19. New York continues to be the epicenter of the coronavirus in the US, with over 353,000 cases and 22,843 deaths as of Thursday.

Even though the situation is daunting, Rami is glad to do his part.

“When they need us,” he said, “we were here to help. We will help people because we are all together fighting this virus, this enemy.”

His caseload quadrupled. Equipment was in short supply. All that improvising back in Syria has proven useful.

“We don’t have gowns, we don’t have masks,” he said.

But it wasn’t that big a deal for him. He remembers thinking, “OK, give me whatever is available, and I will wear it and go.”

And once again, it is Ramadan.

Rami’s long hours at the hospital are again pushing his breaking of the fast a little later into the night, just like back in Jordan, with all those babies born right around sundown. But now, when Rami comes home after a long day of treating patients with COVID-19 and other ailments, he has his family with whom to celebrate.

They share bowls of soup and plates of salad and chicken at a table in their Brooklyn kitchen. It is 4-month-old Kosai’s first Ramadan, obviously. But it is also Rami and Shaza’s first Ramadan together, ever.

“It’s great,” Shaza said. “It’s the first time we are in this together, so I’m so excited.”

Rami added, “I feel like I’m [a] normal person now. It’s a huge change in my life.”

At last, the long fast is over.