More than just a bookstore, The Bookworm in Beijing hosted festivals, screenings and author talks. Over time, it earned its reputation as a vibrant, cultural oasis.

When The Bookworm,a bookstore and cafe in Beijing, announced in November 2019 that it would be closing, there was an outpouring of grief from fans around the world.

Originally founded as a small library in 2005, The Bookworm had become a central hub for Beijing’s intellectual life at its iconic, shell-pink building in the fashionable Sanlitun district. More than just a bookstore, The Bookworm hosted festivals, screenings and author talks. Over time, it earned its reputation as a vibrant cultural oasis.

In a statement posted to The Bookworm’s social media accounts, the owners said they had “fallen prey to the [city’s] ongoing cleanup of ‘illegal structures.’” The bookstore’s closure was the latest in a series of high-profile closures and demolitions since the implementation of Beijing’s urban renewal campaign began in 2017.

Related: What Western media got wrong about China’s social credit system

The Chinese Communist Party aims to make Beijing “a world-class harmonious and livable city,” according to its general city plan for 2016-2035. The plan includes the decentralization of all noncapital functions, the eradication of “urban diseases” such as traffic congestion and air pollution, and capping the capital’s population at 23 million by 2020.

Related: TikTok apologizes after removing video critical of Chinese government

The Bookworm’s general manager and co-owner David Cantalupo, a New Jersey native who has lived in Beijing for over 30 years, would not speculate on whether the bookstore was targeted for its reputation as a cultural hub, popular with both locals and expats. But the bookstore’s former building is owned by a state-run company and is zoned for infrastructure — not commerce, Cantalupo said.

“China is becoming much more rule of law,” Cantalupo said.

The building owners told Cantalupo that because the bookstore lacked proper zoning, they could not renew his lease when it expired in 2019.

According to Cantalupo, in October 2018, the Beijing State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission put new regulations into place, hoping to promote more transparency and eliminate insider dealing. Any property owned by a state-run enterprise must be posted to an online bidding site.

“In many ways, China is doing exactly what we in the West want them to do. I think it’s good that they’re listing the properties and that everybody can see what’s available because China has always been a country where everything’s opaque,” Cantalupo said.

The Bookworm’s announcement of their closure came just a day after the news broke that Duku Books, an online bookseller and publisher, had been forced to close its Beijing warehouse for the sixth time, according to What’s on Weibo, an online publication that reports social media trends seen on Weibo, China’s largest social media platform.

On Twitter, writers, cultural activists and journalists grieved the shutting down of the popular cultural institution as a consummative hit to the city’s diminishing cultural space.

Alec Ash, the author of “Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China,” tweeted:

Beijing resident Andrew Stevens, a frequent patron of the bookstore, also expressed disappointment — and skepticism. “One thing I noticed is that when things started going bad in Hong Kong, they closed down The Bookworm,” Stevens said, referring to the ongoing, violent protests in Hong Kong that began in June 2019 after the government proposed an extradition bill with mainland China.

Stevens asked not to use his real name due to security concerns.

“There’s no proof … but the foreign correspondents’ meetup takes place at The Bookworm. … If they’re going to close The Bookworm, they’re obviously closing a space that the foreign correspondents were using,” Stevens said.

Related: China’s suppression troops have plans for Hong Kong

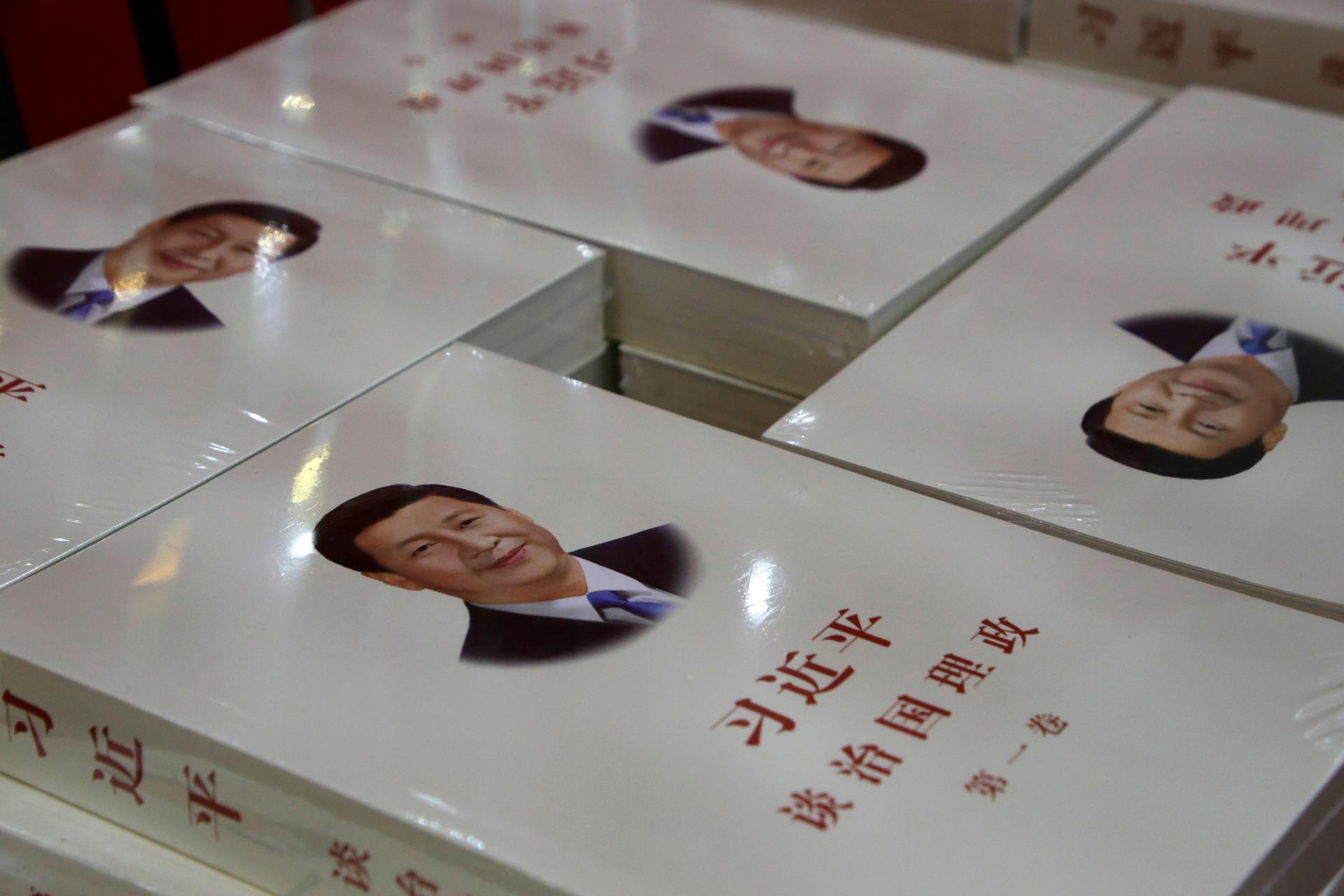

Researchers and activists, as well as many local Beijingers, have argued that as President Xi Jinping tightens ideological control over the country, the Chinese Communist Party is using the latest urban renewal plan to shut down cultural hubs it deems subversive. They point to the authorities’ selective enforcement of long-ignored building ordinances within the plan’s implementation.

‘Modernity and cultural confidence’

According to Jeremiah Jenne, a historian and owner of Beijing by Foot, an educational walking tour company, “a lot of issues [involving] definitions of modernity [and] cultural confidence” are at stake here.

In 2017, during a crackdown on informal settlements and unregulated housing on the city’s periphery, authorities demolished Heiqiao, a decade-old artist village, citing urban redevelopment and the removal of “illegal structures.”

Since the early 1990s, artists seeking cheap rent and larger studios established a series of informal colonies on Beijing’s rural edge, renovating warehouses and renting space from farmers. Until its destruction, Heiqiao was the largest of these communities.

Also in 2017, Iowa Co-op in Caochangdi, an art district established by dissident artist Ai Weiwei, was cited for illegal construction and land use. Police escorted members out as construction workers waited to begin demolition. While under the control of the municipal government and an international hot spot, Caochangdi has faced its rumored end for years as gentrification efforts across Beijing’s outskirts intensify.

Related: Artist Ai Weiwei: Does America still have ‘the big heart?’

In 2018, two Caochangdi galleries occupying land owned by the China Railway Corporation were hit with demolition notices. Also in 2018, Weiwei’s main studio was leveled without warning after initially being given two weeks’ notice, damaging some of the art inside.

The following year, Unirule Institute of Economics, an independent think tank founded by Chinese economists advocating for the free market, was banned by the local Civil Affairs Bureau for being “unregistered and unauthorized.”

In late July 2019, its business license was revoked for operating a website without a permit. This came after years of harassment and eviction for being too loud. In an official statement, executive director Sheng Hong said the ban violated the Chinese constitution’s guarantee of freedom of speech and that the institute planned to appeal.

Jenne pointed out that intellectual and cultural spaces like The Bookworm, Heiqiao and Iowa Co-op only represent one kind of cultural loss in Beijing. Large swaths of local life — such as historic alleyways or hutongs, street vendors, and wholesale and produce markets, have also been eliminated.

In early 2017, in what was dubbed, “The Great Brickening,” residents were displaced when Beijing’s hutongs were partially razed as part of historic preservation efforts. Many of the city’s most dynamic food and beverage establishments were also lost, their storefronts bricked up after being deemed “illegal structures.”

“The party, as much as we can see — because it’s not like they talk about it — has a particular view of modernity that’s somewhere between Coruscant in the ‘Star Wars’ movies, and Pyongyang — with slightly better Wi-Fi,” Jenne said.

“It’s one that doesn’t seem to admit a lot of the organic community messiness that is part of what we think of as street life. And at least for now … that’s what gets stripped away.”

The urban renewal plan is part of one of Xi’s pet projects, the creation of a “hypercity” that encompasses Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei provinces, including an area called “the city of the future.”

Where does The Bookworm exist in this Beijing — city of the future?

Cantalupo is hopeful that he will be able to reopen in another location, carefully following Beijing’s complex regulations. For now, he feels content: “There’s quite a feeling of accomplishment, that this thing that we backed had a pretty significant impact.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?