Alyona Alyona breathes new life into Ukrainian rap scene

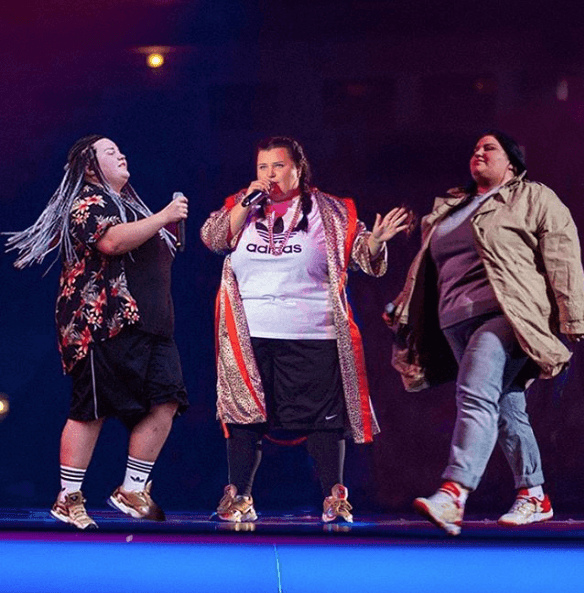

Rapper Alyona Alyona is one of the top artists in Ukraine.

Alyona Savranenko grew up in a small village in central Ukraine. She had a modest upbringing, one she loved — featuring unpaved roads, cows grazing in the field and mushroom picking in the forests.

She enjoyed swimming in the lake throughout the summer and ice skating on it during the winter. When Savranenko turned 6, she started writing poetry, and when she was a bit older, she would write pop songs.

Then she turned 12, and hip-hop found her.

“The first raps I heard were probably American — Eminem. I started translating them.”

“The first raps I heard were probably American — Eminem. I started translating them,” she said. “I looked for his texts, memorized them, and he influenced my flow the most. I liked his style. And I started translating lots of other rappers that I listened to. I was curious what they were rapping about. But I’d always rap about something of my own.”

Today, Savranenko, a former kindergarten teacher, is the biggest rapper in Ukraine. Her music videos — which touch on subjects ranging from body positivity to bullying and female empowerment — rack up millions of views on YouTube, and she has been on multiple European tours. The hugely popular 28-year-old prides herself on defying the stereotype of what rappers look like in Eastern Europe and the rest of the world.

Something about hip-hop clicked with Savranenko. There was space and freedom to express herself — like the poetry she used to write, but without all the rigid rules.

Related: Ukrainian folk punk band DakhaBrakha sings a decidedly feminist message

Ukrainian rap, gangsta style

Hip-hop in Ukraine became popular by the late 1990s. It largely emerged from Kharkiv, a city in eastern Ukraine not far from the Russian border, says Adriana Helbig, an associate professor of music at the University of Pittsburgh.

“That was the home of a group called Tanok na Maidani Kongo [“Dance on Congo Square”], and they had won a Ukrainian-language festival competition with their rap, ‘Make me a hip, make me a hop,’” said Helbig, author of “Hip Hop Ukraine: Music, Race and African Migration.” “That’s what sort of established hip-hop as a genre — a legitimate genre, a Ukrainian-language genre. Until then, anything that was coming into Ukraine was English language and also it was much more dominated by the Russian-language sphere.”

As Savranenko got older, writing rap lyrics became part of her life.

“I started writing first not about some fantasy stories or made-up fairy tales, but about what was happening around me,” she said. “Some of the stuff that I was rapping about, though, wasn’t even very truthful. I really wanted the Ukrainian rap community to accept me, so I rapped about using drugs and some of the street life that I saw around me — the kind of lifestyle that wasn’t really mine.”

Early hip-hop in Ukraine was hugely influenced by African American and Russian rap, Helbig said, where violence and drugs are major themes.

“And the reason was, in part, because [Ukrainian rappers] were growing up in the sort of impoverished urban areas on the outskirts of cities,” she said. “These guys are reacting to the videos that they’re seeing coming out of the United States, so they were very much replicating and connecting with this form of poverty, alienation, everything else.”

Related: Ukraine’s Eurovision 2016 entry is about Stalin’s repression, and Russia isn’t thrilled

When she first started rapping, Savranenko also embraced American gangsta-style rap because she thought that’s what hip-hop was supposed to be about.

“But I wasn’t gangster and criminal. I was just a teacher in the kindergarten, but all the rappers respected me.”

“But I wasn’t gangster and criminal. I was just a teacher in the kindergarten, but all the rappers respected me,” she said.

Savranenko kept her job as a kindergarten teacher, but she also kept rapping and getting more attention.

Eventually, she took on the rap name Alyona Alyona, writing lyrics in Russian because many of the rappers she listened to were Russian.

Language politics

During the Soviet period, the Russian language dominated the official political and cultural sphere. But after Ukraine became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, there was a rise in Ukrainian language use. Still, when it comes to rap, the politics around language have been more practical, Helbig said.

Related: This Ugandan rapper was ‘miseducated,’ Lauryn Hill-style

“For instance, a lot of the musicians that I would talk to just said that it was easier to rap in Russian because you could curse,” Helbig said. Russian-language profanities are commonly used throughout the former Soviet Union, and some artists say it sounds more aggressive.

The politics between Russian and Ukrainian language have now started to soften, Helbig said, partially because younger people have more access to learning and using Ukrainian. But in 2014, Ukraine went through the Revolution of Dignity, where Ukrainians started expressing a stronger sense of pride in Ukrainian language.

Savranenko said she felt the same. She read more Ukrainian literature, and she was teaching mostly in Ukrainian.

“My vocabulary in Ukraine language was bigger and bigger, and I start[ed] rapping in Ukrainian language.”

“My vocabulary in Ukraine language was bigger and bigger, and I start[ed] rapping in Ukrainian language,” she said.

It’s a linguistic trend that’s playing out across Ukrainian hip-hop.

“There’s much more of a wide range of ideas that you can express in Ukrainian and also the hip-hop itself is changing, which might account for Alyona Alyona a little bit,” Helbig said. “Ukraine has sort of been blossoming and really moving into its revival of folk, and it has all these very interesting dynamics that they’re trying to push into their own identities. And women have a very important role.”

Ukrainian has also been historically gendered, she added.

“Russian tends to be more of a masculine way, and Ukrainian tends to be positioned as the more the feminine way,” Helbig said, adding that Ukraine is often figuratively depicted as a woman taken captive by Russian soldiers.

That might be evident in Savranenko’s music, too.

‘I just accepted myself’

The song “Ribky,” which translates as “fish,” was Alyona Alyona’s first hit, with more than 2 million views on YouTube.

At face value, the song is simply about the title animal — the way they look, and the way they swim. But a deeper listen reveals more — and the song is really about how powerful fish can be, Savranenko said.

“Most people understood what the song was about. That it’s not about fish and water, but about girls,” she said.

At the time Savranenko was growing up, Ukraine had a “very gendered division of society” — a backlash to the “gender neutrality” presented in the Soviet Union, Helbig said.

“The reaction to that in the early 1990s is you have this hypermasculinity of this machismo mafia type [and] the women were being pushed into the hypersexualization of, like, prostitution,” Helbig said. “There’s a lot of violence against women. There’s a lot of rape. … This is very much playing out, especially in the villages.”

Alyona Alyona’s music looks at girls and their place in society — girls who are bullied because they’re different, and girls who face abuse for their weight or their style. Body positivity is also a big theme in her music.

“One of the things I was thinking of is really just how powerful [Alyona Alyona] is and what kind of statement she’s making.”

“One of the things I was thinking of is really just how powerful [Alyona Alyona] is and what kind of statement she’s making,” Helbig said.

The track “Pushka,” which roughly translates to “the bomb,” takes on the subject as well. In it, Alyona Alyona calls herself a “pishka,” a Ukranian word used as an insult for people who are overweight.

But Alyona Alyona appropriates the word — she makes it her own, and carries herself with swagger.

“That’s part of my life. I’ve encountered a lot of body shaming, fat shaming, bullying in my life. But mostly it’s people who motivate me because they keep asking, ‘How can you be so cool?’” she said. “I tell them I’m like everyone else, I just accepted myself the way I am. I realized people need my experience and I started sharing it. With some — in messages, with others — in songs.”

And Alyona Alyona hasn’t wavered from that positive message. She rarely curses in her music, and that gangsta-rap style from her early days is long gone.

One of her recent tracks is all about standing up to bullies.

“We decided to make a music video where I play different characters: a goth, a basketball player and others — showing this way that every person has a second half of themselves,” she said. “We shouldn’t be afraid to be ourselves, shouldn’t be afraid to resist, to stand strong against bullying. We shouldn’t be silent about it. It’s necessary to pull out that other half and fight.”

In Ukraine, Alyona Alyona is one of the country’s top artists, and she’s toured all over Europe.

“So, I thank God that I have [the] possibility to introduce my country and my music in European countries, and I will be do[ing] this in the future because I don’t want to rap in other languages,” she said. “I’m not ready, I don’t have so many words to sing in English or in Russian. I want to do it in Ukrainian.”

Helbig says Alyona Alyona is also helping combat Ukraine’s history of generational trauma.

In Ukraine, “anxiety among everyday people is extremely high, and here you’ve got this kid that’s, you know, happy. … ‘Let’s smile. Let’s rap about fish. Life’s great.’ And it’s like, what is this person doing?” Hebig said. “But on the other hand, you almost can’t help but embrace it.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?