Three large royal statues of the Kingdom of Dahomey, from left to right, half-man half-lion of King Glele attributed to Sossa Dede, Benin, Abomey (1858-1889), half-man and half-bird of King Ghezo, attributed to Donvide or Sossa Dede, atelier Akati, Benin, Abomey, (19th century) and half-man and half-shark of King Behanzin, attributed to Sossa Dede or the Houeglo family, Benin, Abomey (1890-1892), are displayed at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris, Nov. 23, 2018.

When French soldiers began an incursion against the West African Kingdom of Dahomey in 1890, King Béhanzin sent his fiercest soldiers to defend the front line.

The troops were an elite squadron of women warriors often remembered as “Amazons.“

The French eventually defeated the kingdom, looting expensive jewelry and clothes that belonged to the women warriors. These precious objects speak to the warriors’ importance to the Kingdom of Dahomey that once ruled parts of modern-day Benin. The French colonized Benin until 1959.

“It’s interesting to see that these Amazon had very beautiful necklaces, very expensive ones. That means that they aren’t women fighting like men, they are women fighting like women,” said Alain Godonou, national director of museums in Benin.

In December 2019, France announced a deadline to return 26 objects taken by French colonial military leader Alfred-Amédée Doddsin the 1890s back to Benin by 2021 amid a growing call for the restitution of African art taken during colonial periods.

“We went through the list of 26 and we are asking to have three or four [other] important pieces [added] for our history.”

“We went through the list of 26, and we are asking to have three or four [other] important pieces [added] for our history,” said Godonou, who is vice president of the museum and heritage cooperation committee between Benin and France.

Negotiations about which objects will be returned are still ongoing. The original list of 26 objects didn’t include a special piece of jewelry.

Godonou grew up hearing about the fierce women warriors of Dahomey and remembers the first time he saw one of their jewelry pieces in France about 15 years ago. It was a delicate necklace made out of glass beads strung together, reminding Godonou of a linceul des saints or “a holy shroud.”

To Godonou, who has worked in Benin’s museums for decades, the necklace is one of the country’s most important pieces of art — even when compared to the large, wooden statues and elaborate metal swords thatalso characterize the cultural heritage of the Kingdom of Dahomey.

“It’s the perfect symbol of women engagement against a colonial army,” Godonou said.

Their symbolic importance is one of many reasons why Benin is officially requesting the necklace back from France, which has housed the necklace since it was taken by French colonial soldiers more than 100 years ago.

The announcement comes years after French President Emmanual Macron made a more ambitious promise during a speech at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. “I cannot accept that a large share of several African countries’ cultural heritage be kept in France,” said President Macron, who has set a precedent by being a European statesman willing to speak frankly about the dark elements of France’s colonial legacy in West Africa.

“Within five years, I want the conditions to exist for temporary or permanent returns of African heritage to Africa,” Macron said.

In 2018, Macron commissioned a report on France’s national art collections written by Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy. The now infamous report shocked the art world by calling for the immediate restitution of African art looted or stolen during the colonial era.

“Restitutions open up a profound reflection on history, memories, and the colonial past,” the Sarr-Savoy report says.

Indeed, Macron’s call for restitution goes well beyond art alone.

“What is at stake is the debate is the redefinition of the relationship between African countries and European countries past the moment of decolonization.”

“What is at stake in the debate is the redefinition of the relationship between African countries and European countries past the moment of decolonization,” said Cécile Fromont, who teaches West African art at Yale University in Connecticut. Fromont sees the report as an opportunity to usher in a new era — and a new relationship — between France and the African countries they once colonized.

This relationship has received renewed scrutiny in recent years, with calls to abandon colonial-era currencies and protests against French military engagement in the Sahel. Some have even accused France of trying to maintain a tight grip on countries that were once colonized.

“Macron is part of a completely new generation,” said Fromont. “In 10 years, we go from the Sarkozy speech that presents Africa as backward without history to the Ouagadougou speech by Macron that calls for a new era in the relationship between France and Africa.”

For African curators, the generational shift is clear.

Godonou, for example, can still recall a time when he was not allowed to intern at France’s Musée de l’Homme, which boasts an extensive collection of African art. “I was not accepted because, I think, I was African,” Godonou said. “It was something that hurt me. It was the first thing I wanted to do, the first place I wanted to be to learn about African art. The best place in Paris at the time was Musée de l’homme.”

The experience propelled Godonou to commit to growing art institutions within Benin and Africa at large. In 1998, Godonou founded the School of African Heritage in Porto Novo, Benin’s capital. He later served as the director of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Libreville, Gabon.

Yet, the expansion of art and cultural heritage programs and infrastructures in Benin over the past decade has not obscured the absence of the country’s most important pieces, which continue to fill the stands of private collections or museum exhibits in France and other countries.

“We need pieces that are important for our history and which [are] not here now,” Godonou said. “We need these important pieces from [the] Amazon [women warriors] that we noticed … were in France, but not at all in Benin.”

Macron’s commitment, while enmeshed in politics and diplomacy, presents a new opportunity for the return of these artworks. Many African countries have been making requests for decades — but they have often fallen on deaf ears.

“Restitution is a highly political and emotive subject matter. It’s also a really drawn-out process because there are no international conventions that really consistently govern the return of cultural property. Particularly from the colonial era,” said Azmina Jasani, an art and cultural heritage lawyer at Constantine Cannon LLP in London.

Jasani notes that even given the new political will from Macron, French law restricts the complete return or restitution of artworks. “French museums have classified every object that has entered into their inventory as important cultural heritage. As a result, France will need to pass new legislation allowing for artifacts to be deaccessioned each time it wants to restitute something.”

Still, France has signaled that it is willing to use other options, like long-term loans or exchanges, to fulfill its promise.

In November 2019, France returned a 19th-century sword to Benin on a long-term loan. The sword once belonged to West African leader Omar Saidou Tall, who fought France’s colonial pursuit.

“Restitution is a highly political and emotive subject matter. It’s also a really drawn-out process because there are no international conventions that really consistently govern the return of cultural property. Particularly from the colonial era.”

The Sarr-Savoy report has also prompted new debates about art restitution in other former colonial powers.

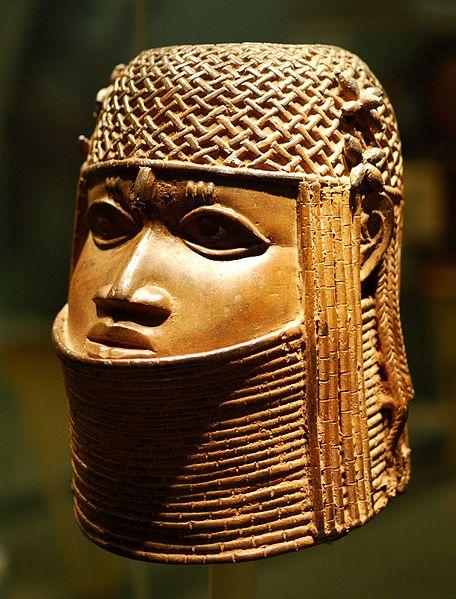

In December 2019, the University of Cambridge announced it would return a bronze cockerel statue whose origins trace back to the Kingdom of Benin, which governed parts of modern-day Nigeria.

For some, this underscores the challenge in deciding who owns art from the colonial period.

“Nigeria only became a reality in 1914. Benin Kingdom was destroyed and the art objects [were] stolen in 1897,” said Ndubuisi C. Ezeluomba, curator of African art at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Ezeluomba also grew up in Benin City, once the capital of the Kingdom of Benin.

Ezeluomba argues that there should also be more of a focus on investment in art infrastructure in Africa, a topic that often receives scrutiny in the middle of restitution debates.

“To say that someone can’t take care of art as well as we can is not the right one,” argued Victoria Reed, a provenance researcher at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Related: Nigeria to the world: Give us our art back!

In 2014, the museum returned eight works of art back to Nigeria once they determined they had been looted. Reed argues that even when works are not returned, institutions have a duty to be transparent about how artwork is acquired. “Our visitors not only want to know this information, but we have a responsibility to share it with them.”

In this politically charged debate about restitution, museum visitors, especially youth, are also at the forefront of Godonou’s mind. He once led youth programs in Benin — bringing museum outreach to local communities.

“It makes a difference when youth come across the African arts. Sometimes, they can’t believe that it’s from their country,” Godonou said. “I come across some people and they say, ‘No, it’s not from here’ and I say, “Yes, it is from here.””

For Godonou, access to Benin’s cultural heritage is a matter of pride and confidence. “It’s really important for youth to see that in the past and history, their ancestors used to do so well.”

While negotiations between France and Benin are ongoing, Godonou hopes that the artworks, especially the necklace of the fallen woman warrior, will be returned this year, just in time to celebrate 60 years of independence Benin — then called Dahomey — from France.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?