British Columbia gets creative to combat drug overdose crisis amid coronavirus

At 61, Henry Fester can barely remember a time he wasn’t using drugs. He’s attempted treatment several times in the past, but nothing ever stuck in the long term.

Fester, who lives in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighborhood, says it’s not even about getting high anymore. Rather, it’s to avoid the chills, shakes, fevers and pains.

“That’s basically all I’m doing is fighting off withdrawal,” said Fester, who spent years working in film and television.

Related: In Canada, some doctors are prescribing heroin to treat heroin addiction

It requires a lot of time and energy, planning for the next hit. But recently, he says, life has been easier. That’s because Fester’s stash now comes straight from the drugstore, thanks to a legitimate prescription for hydromorphone, a pharmaceutical alternative for heroin. He only has to go to the pharmacy once a week to pick up his supply of pills, which he crushes and injects at home every few hours as needed.

Fester says it’s a relief. He’s able to think about other things — not just drugs.

“I’m so lucky to have what I have.”

“I’m so lucky to have what I have,” he said.

Fester’s new normal is due, in large part, to the pandemic. British Columbia was already battling a major health crisis — skyrocketing overdose deaths — when the new coronavirus emerged. Concerns mounted that these dueling emergencies, compounded, could lead to an even bigger public health problem. So the government decided to try something unusual.

Related: In Vancouver, people who use drugs are supervising injections and reversing overdoses

In March, it approved new guidelines for supporting people with drug addictions during a lockdown. The guidelines make it easier for doctors to prescribe controlled substances such as opioids and stimulants, off-label, as replacements for people who would otherwise seek out similar drugs on the street.

It also allows for extensions in take-home prescriptions for medication-assisted therapy like methadone, encourages more virtual doctor visits and relaxes the number of recommended in-person drug tests.

“We knew we had to act quickly in the context of a dual public health emergency in order to keep individuals who were struggling with addiction safe and to keep the community safe from COVID-19,” said Judy Darcy, British Columbia’s minister of Mental Health and Addictions.

Darcy said the province has been in emergency mode for years, in part because of a tainted illicit drug supply — it has been laced with a highly potent synthetic opioid called fentanyl, which has led to a surge in overdose deaths. In response, since 2017, the province has ramped up treatment programs and other interventions like consumption sites, where people can use drugs under supervision.

Related: Caravans to Canada: Americans desperate for affordable drugs spark concerns about shortages

Enter the pandemic. Border closures have interrupted global supply chains, and it has affected the illegal drug trade. Major ingredients for fentanyl and meth often come from China, and more specifically, Wuhan, where the coronavirus outbreak was first discovered. Darcy worries local dealers have been filling that gap with who knows what.

“Things have never been worse as far as the toxicity of the drugs and them being adulterated with more dangerous substances than before.”

“Things have never been worse as far as the toxicity of the drugs and them being adulterated with more dangerous substances than before,” she said, recounting anecdotal reports coming into her office.

Related: ‘We can’t take our health for granted’ as US reopens, says Dr. Howard Koh

It’s too soon to draw solid conclusions as health services, in general, have also scaled back due to the pandemic. But Darcy and others sounded the alarm in March when suspected overdose deaths reached 113 in British Columbia, the highest monthly level in a year.

The B.C. Centre on Substance Use, or BCCSU, is the agency that put together the guidelines and brought in outside reviewers. Creating a “safe supply” of drugs makes sense right now, said Cheyenne Johnson, interim co-director of BCCSU. But she says it’s not meant for everyone and requires a nuanced approach.

“It really is individualized based on the individual person’s medical history, what substances they use, how they use them,” Johnson said. “Have they had an overdose in the past? Have they tried treatment? If they have, what have they tried? How has it worked for them? What are their health goals?”

If people want to access treatment during the coronavirus lockdowns, Johnson stresses there are opportunities to do so. Addiction is complicated, especially in a period of increased isolation. Some specialists worry that overdoses might go down during a time of lower quality and supply, only to spike up in the future once virus restrictions ease and the supply returns.

“What I’m concerned about are the vicissitudes in supply and the rebound effect.”

“What I’m concerned about are the vicissitudes in supply and the rebound effect,” said Dan Ciccarone, an addiction doctor and drug researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. He points to possible lessons from a “drug drought” in western Canada and Australia in the 1990s.

The current challenges may also be compounded by poverty, subpar housing and other mental and physical health issues. The new mitigation guidelines in British Columbia, according to Johnson, are just one part of trying to limit the spread of COVID-19 and reduce people’s risks.

“If you use drugs, then you need to be out on the street to purchase and procure drugs multiple times a day while also doing activities like perhaps, just survival sex work or recycling activities like collecting cans to make the money to purchase those drugs,” Johnson said. “And so, that puts those individuals, you know, out in contact with folks much more.”

For now, British Columbia has not experienced a major surge in coronavirus cases, as was feared. About 2,500 cases of the coronavirus have been reported, plus about 150 deaths.

Even before the pandemic, the Canadian government had supported several programs for prescription heroin. It has been researched for people who just don’t latch on to other treatments. But these new, broader guidelines which include prescriptions for other drugs like Ritalin and benzodiazepine, and less supervision, is uncharted territory.

It’s unclear just how many doctors and nurse practitioners are on board with the new guidelines, how well it will actually work, and for how long it will stay in effect. Even doctors on the front lines of the crisis, who led the push for a safe drug supply well before the coronavirus, have some concerns about how this is all done.

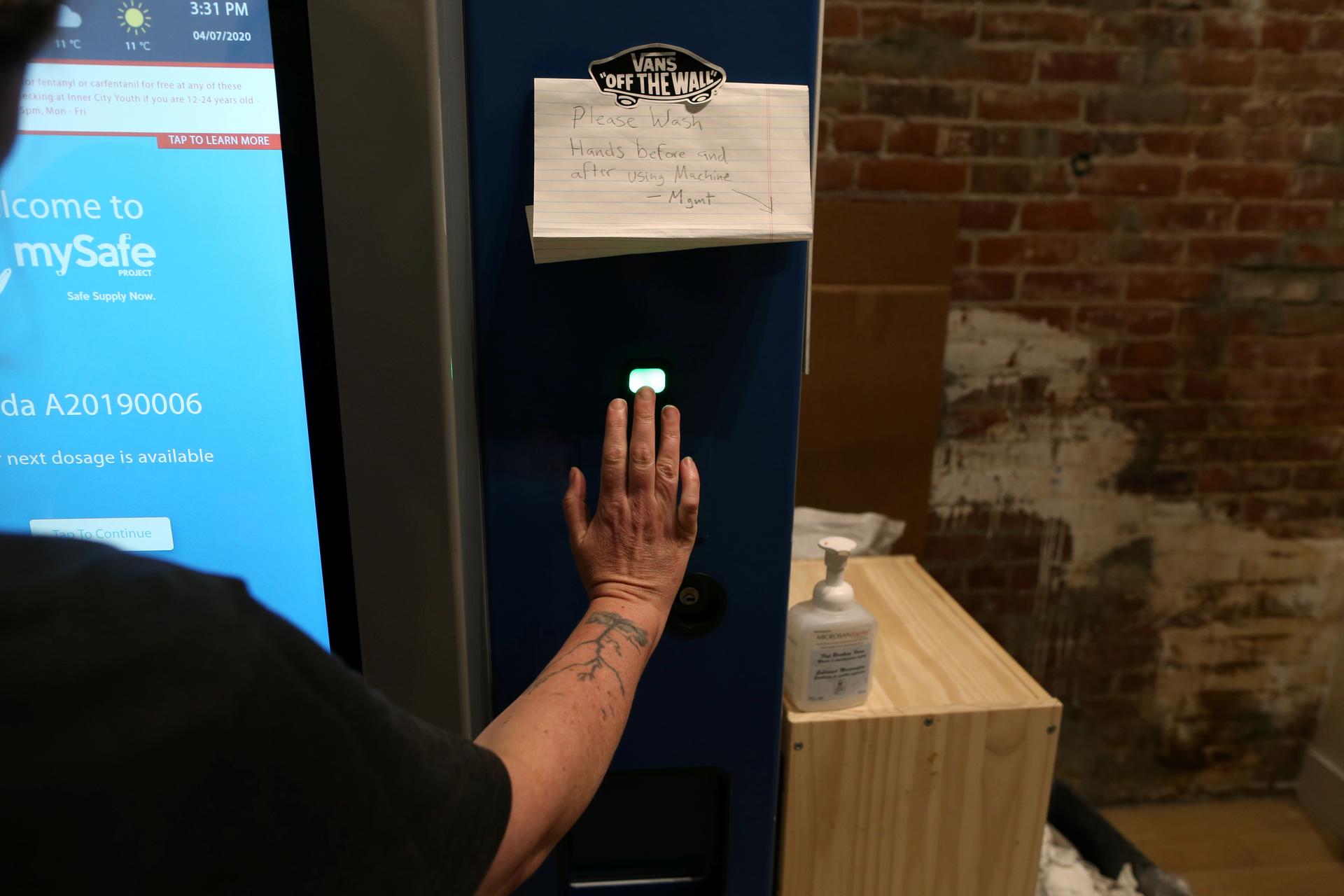

Dr. Mark Tyndall, a professor at the University of British Columbia, developed a kind of safe supply opioid vending machine that was finally up and running right before the pandemic. He is now prescribing drug replacements to people but says he is doing so carefully, especially for extended prescriptions.

“It’s really operationally very difficult to give people, you know, a large supply of drugs and tell them to go sit in a room and use them over two or three weeks [if they need to isolate due to the coronavirus]. It’s like giving somebody with a gambling problem, you know, a million dollars and telling them to save their money. I mean, it’s just not fair to the people getting the drugs, even.”

“It’s really operationally very difficult to give people, you know, a large supply of drugs and tell them to go sit in a room and use them over two or three weeks [if they need to isolate due to the coronavirus],” Tyndall said. “It’s like giving somebody with a gambling problem, you know, a million dollars and telling them to save their money. I mean, it’s just not fair to the people getting the drugs, even.”

About 400 patients are getting prescriptions under the new guidelines, the majority of which is for an opioid, like hydromorphone, according to Darcy, with the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

Fester, who’s one of those receiving an extended prescription that only needs to be filled once a week, says his life has totally changed. He has reconnected with family and a teenage granddaughter.

“I started to get my life back,” Fester said. “This is what it used to be like before I lost control, you know? It has given me time to reflect on what life is all about as well.”

He’s mainly confined to his home and is restless like so many others because of the current COVID-19 restrictions, but for him, this moment marks newfound freedom.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?