In his 1960 bid for the White House, John F. Kennedy’s campaign wooed a voting bloc that was mostly forgotten by other political campaigns: Latinos.

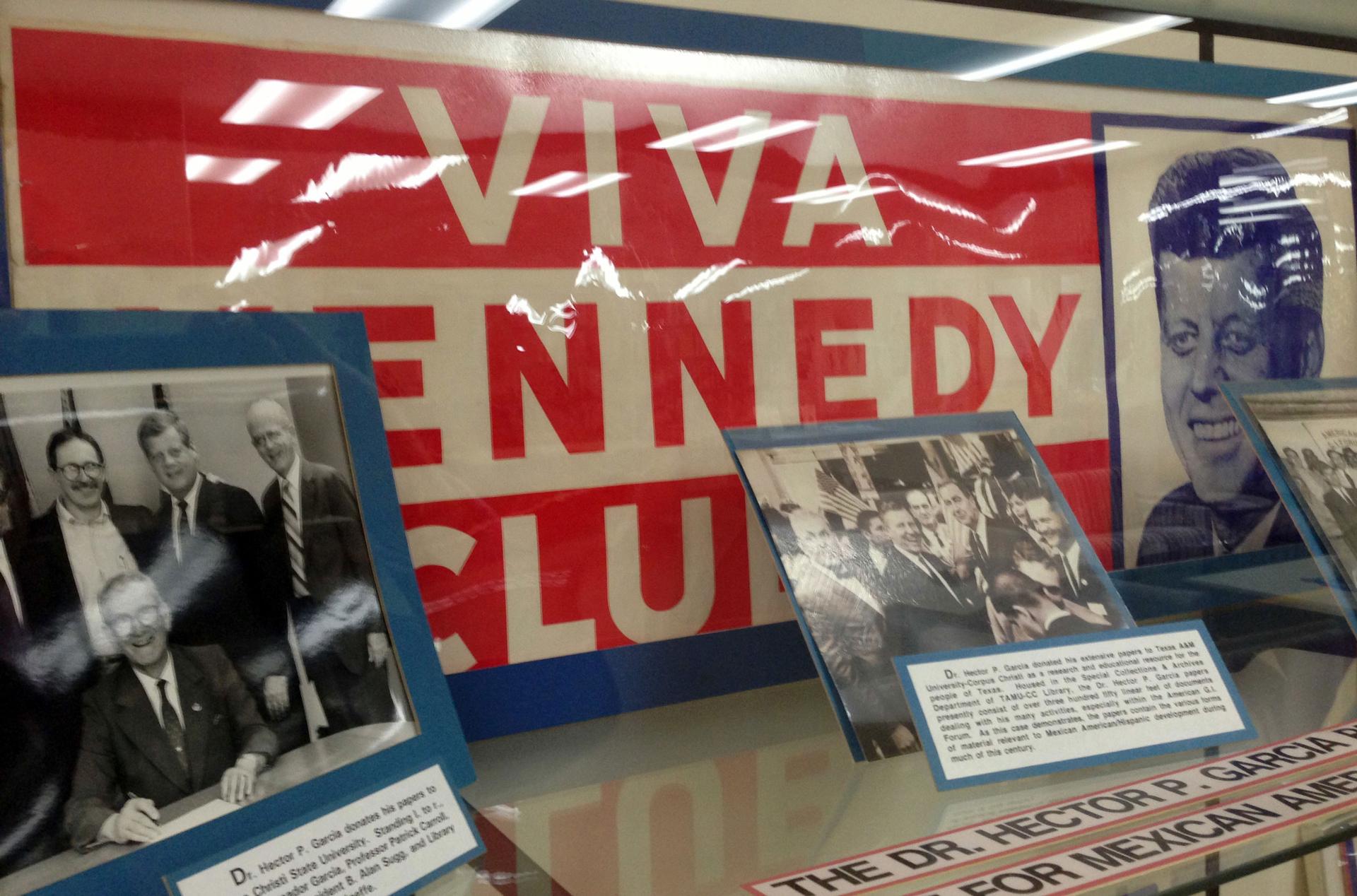

Jackie Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s wife, took to the airwaves with her own Spanish-language ad urging people to vote. She ended the ad with “Viva Kennedy!” — a slogan that became a unifying phrase for a group of Mexican American political organizers in Texas.

The Viva Kennedy Clubs, as the groups came to be called, spread their efforts across the United States and pushed regional Latino issues — such as housing, unemployment and school segregation — to the forefront of the Kennedy campaign. At the same time, Kennedy earned the vote of Mexican Americans and other Latino groups in key states such as Texas and Illinois.

It was the first time a candidate for the nation’s highest office tried to court Latinos, who numbered about 6 million at the time, roughly 3.5% of the US population. Kennedy was early in recognizing Latino voters as a growing force in American politics. The clubs helped paint Kennedy as a friend, someone they could relate to. He was an Irish Catholic who cared about Mexican Americans and other Latino communities. Kennedy received about 85% of the Mexican American vote that year.

Ignacio Garcia, a history professor at Brigham Young University in Utah, said Kennedy’s effort in 1960 was the first time a political campaign was successful in helping elevate Latino issues to a national audience.

Most of that success, he said, comes from allowing the Viva Kennedy Clubs to operate independently from the Kennedy campaign. The clubs controlled everything from speakers at Latino-focused rallies to logos, fundraisers and posters — as well as Kennedy’s message.

“There were things that Kennedy had never even heard of or had never promised,” Garcia said. “There isn’t a huge history of that for them, particularly as the politicians, and political and social leaders in each community begin to connect with each other. So, this is where you see the first connections between different Latino groups.”

Latino mobilization post-Kennedy

Other milestone movements that continued to attract the Latino vote came in 1965 and 1971.

When the Viva Kennedy Clubs disbanded soon after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, some of the organizers worked hard to keep issues important to Latinos on the political agenda. But they didn’t rally behind particular Democratic or Republican candidates. Instead, they created the La Raza Unida Party and ran Latino candidates on that ballot.

The creation of La Raza Unida Party — or the United Race party — was a way to ensure Latinos and their concerns were taken seriously. Former Kennedy supporters felt Kennedy had not kept his promises after helping him get elected in 1960.

Just as the Viva Kennedy Clubs had done before, La Raza Unida Party movement also spread across the country.

But while candidates under La Raza Unida were not always elected, the movement did keep many young Latinos politically engaged, Garcia said.

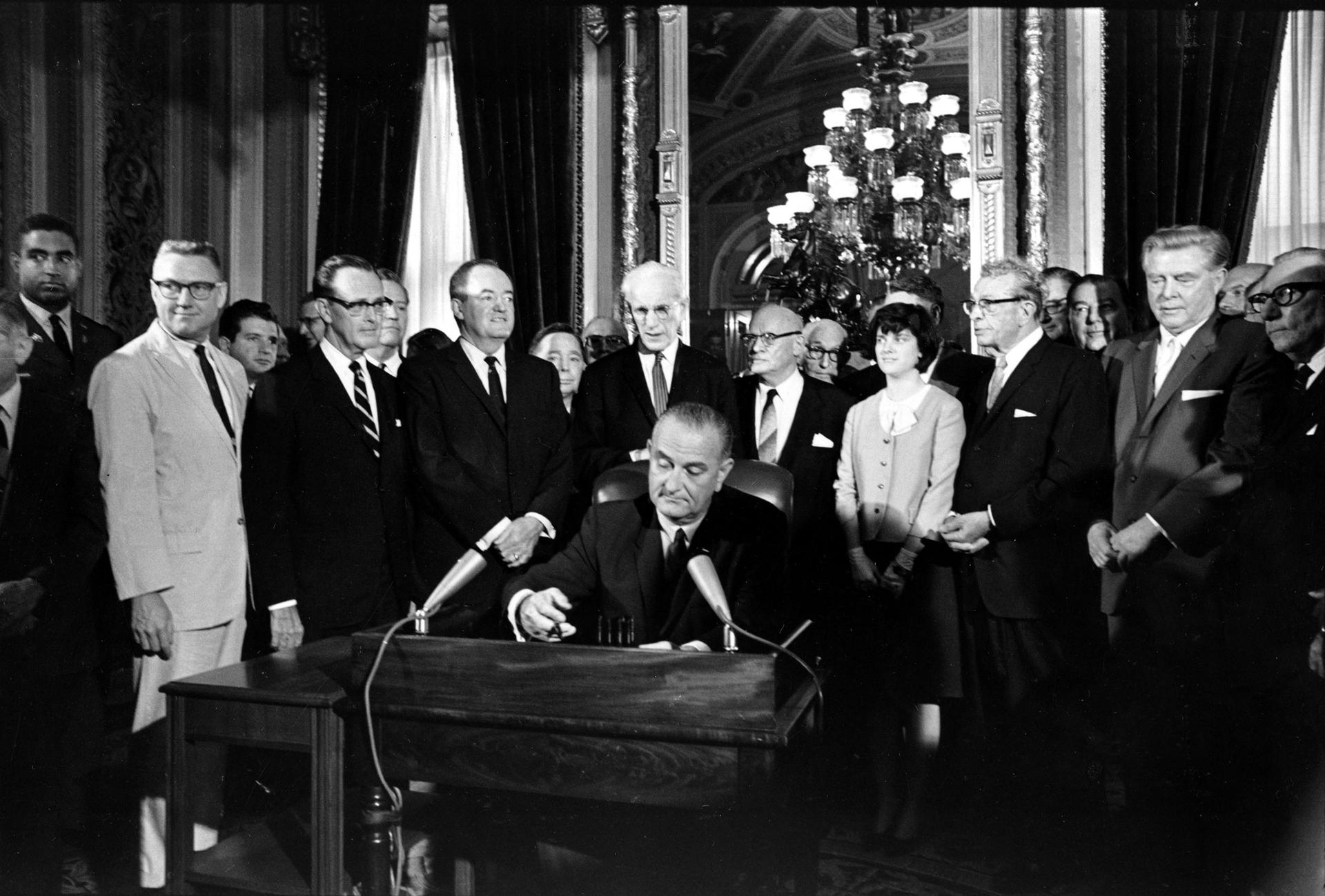

And keeping Latinos engaged beyond the clubs was a top priority for Latino politicians and other political organizers. This helped when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“Millions of Americans are denied the right to vote because of their color,” Johnson said during his remarks to Congress when he signed the proposal.

Blacks and Latinos faced some obstacles when it came time to vote, such as having to take an English test or pay poll taxes. This shut people out of the voting process, including immigrants eligible to vote.

Several years later, in 1971, President Richard Nixon lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. “That just opens the floodgates because now younger people … will now get the opportunity to participate in the electoral process,” Garcia pointed out. Major voter registration drives across the country took place. Groups like the Southwest Voter Registration and Educational Fund and the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) led this effort.

At the same time, a parallel movement began unfolding in Southwestern states: unions and farmworkers were coming together to demand better working conditions. Activist Cesar Chavez, who led the United Farm Workers union alongside Dolores Huerta, began endorsing candidates and getting more Latinos involved.

Latino communities connected as they pushed to nationalize issues and practices that were once considered local or regional. The push for more political representation got stronger. Meanwhile, immigration enforcement got tougher, affecting many Latino communities in the US and mobilizing them to organize for fairer immigration laws.

It’s a lot like what happened in 2006 — many years later — when thousands of people took to the streets in major US cities to protest anti-immigration laws, shouting, “Hoy Marchamos, Mañana Votamos” — Today we march, tomorrow we vote.

“We must make sure that we’re working in our communities every day between now and October, to register, to mobilize and to vote. We have that power to have our voice heard in November. Así vamos a seguir adelante. Si Se puede,” said Janet Murguía in 2006, then president and CEO of National Council of La Raza, a Hispanic advocacy organization.

How Latinos could influence the 2020 election

Today, as the 2020 presidential election approaches, civic groups have mobilized to get as many Latinos registered to vote as possible — especially as the number of eligible Latino voters grows. But it’s not easy.

“In many ways, the challenges remain incredibly difficult, and the one difficulty always in voting registration is convincing people that participating actually makes a difference,” Garcia said.

A record 32 million people who identify as Latino will be eligible to vote in the 2020 presidential election, according to Pew Research Center. That’s just over 13% of the electorate — surpassing eligible black voters for the first time and making Latinos the nation’s largest voter group after whites. It’s now routine for candidates to spend millions on Latino voter registration and outreach.

The challenge for candidates will be getting Latinos to come out and vote on Election Day. For decades, the Latino vote has been referred to as a “sleeping giant.” But at times it seemed the giant never fully woke up: Despite huge increases in the Latino population, voter turnout among Latinos has historically lagged behind other racial and ethnic groups.

That’s something Antonio Arellano, a political organizer in Texas, wants to change this year.

“We don’t have voter registration campaigns, we have what we call culture-shifting campaigns,” Arellano said.

Arellano is with Jolt Action, a Latino civic organization that wants to increase Latino voter participation. Unlike groups that mainly go door-to-door or call potential voters, on the phone, Jolt is trying a different approach: The group is behind a new initiative called Poder Quince or “Quince Power,” that uses quinceañera parties — or coming-of-age celebrations for young Latinas turning 15 — to register people to vote. The quinceñera, or birthday girl, gives a speech to her family and friends — usually 100 to 200 guests — explaining why voting matters to her. She then tells her guests to register to vote at a Jolt-sponsored booth in the back of the party venue.

Young Latinos have become a large voting bloc. Unlike their parents and grandparents, most Gen Z Latino voters (those aged 18 to 23) — 95 of every 100 — were born in the US. Arellano said this group could help flip Texas from a red to blue state.

“And this year we’re aiming to attend 500 quinceaneras in Texas alone,” Arellano said. ”We are ready to mobilize this constituency that is thirsty for change.”

This story is part of our “Every 30 Seconds” series, produced with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.