South Korea wants to draft more men for its shrinking military — and punish those who dodge

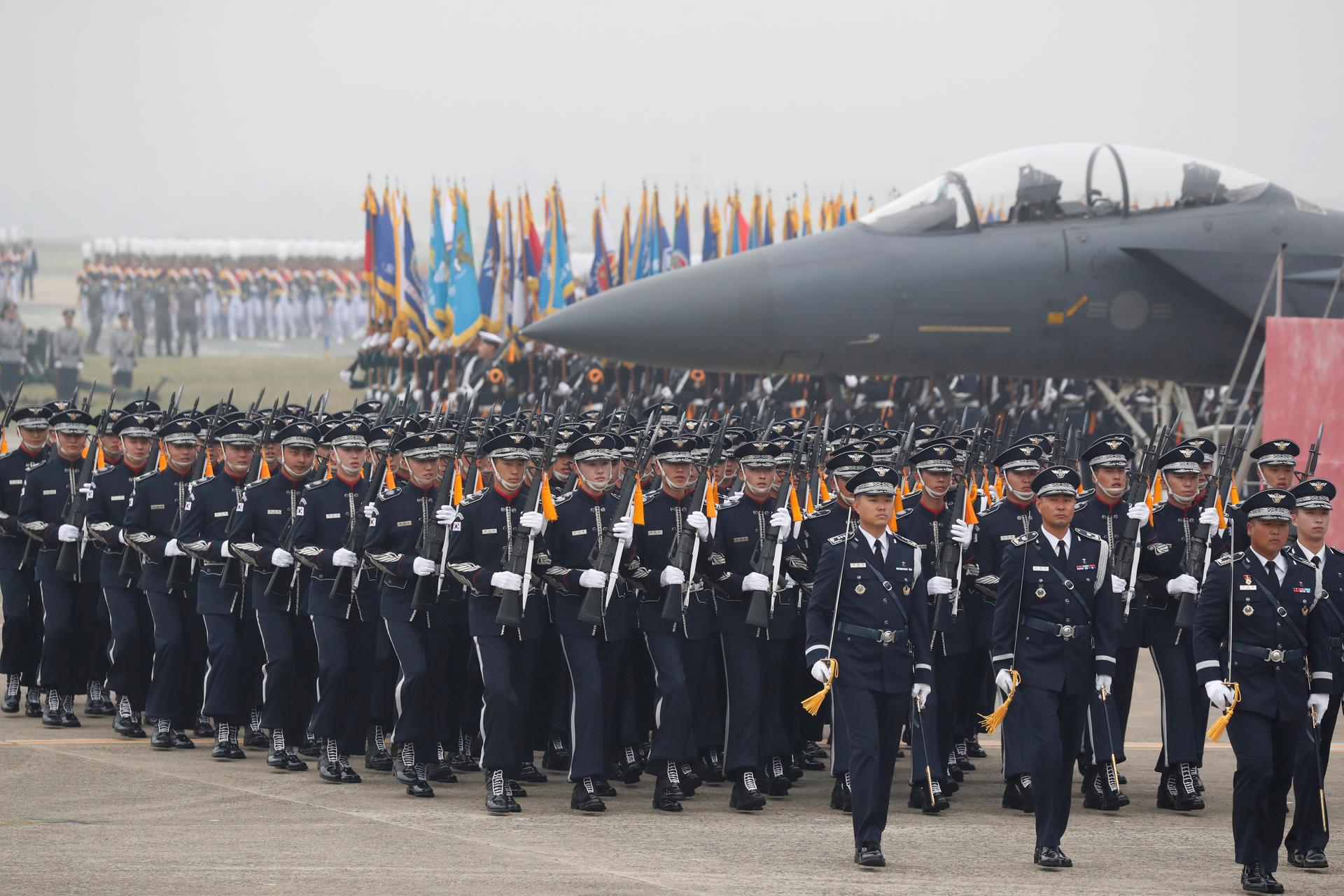

South Korean Army soldiers participate in a ceremony to mark the 71st anniversary of Armed Forces Day at the Air Force Base in Daegu, South Korea, Oct. 1, 2019.

Young Chun — an American citizen born and raised in Illinois — doesn’t look back at his military service in South Korea fondly. Now 41, he remembers how soldiers mocked his broken Korean. Higher-ranking officers screamed at him for looking at his pocket dictionary while walking. He had to wipe down golf balls for his superiors.

“The military wasn’t as bad as I imagined it would be … it was far worse.”

“The military wasn’t as bad as I imagined it would be … it was far worse,” said Chun, who was forced to serve from 2004-2006.

In South Korea, able-bodied male citizens between the ages of 18 and 40 are required to serve in the military for nearly two years. Refusing the draft means prison time, while dual citizens must decide to serve or give up their South Korean citizenship within the year they turn 18.

Related: Charging South Korea more for US troops would ‘turn us into mercenaries,’ expert says

With a growing population crisis and technically an ongoing war with North Korea, South Korea may start to forcibly conscript more overseas Koreans and foreigners. The government-run Korea Institute for Defense Analyses is currently wrapping up research around the idea of drafting naturalizedcitizens — those who gain South Korean citizenship, but aren’t born with it — to cope with the country’s dwindling number of troops.

Related: Will North Korea accept food aid from South Korea?

Chun was a special case: Born and raised in the United States, he identifies as an American. He had no idea at 18 that he was also a South Korean citizen who had to serve or give up his citizenship — it wasn’t until he got his draft notice while working as an English teacher in Seoul. The letter included a notice from the Ministry of Justice that banned him from leaving the country.

“I was really shocked. I talked to lawyers, I talked to newspaper reporters — I tried joining the US military instead,” said Chun, who wrote a memoir about his experiences called “The Accidental Citizen-Soldier.” “Everyone told me basically, ‘You could try to fight it, but it would take a long time, you probably won’t win and it would be very expensive.’”

Now, more overseas Koreans and foreigners may soon find themselves forcibly conscripted like Chun. As early as next year, the South Korean government could begin revising its Military Service Act.

“We are facing a population crisis, and we’re trying to figure out how we can increase the number of soldiers in our country.”

“We are facing a population crisis, and we’re trying to figure out how we can increase the number of soldiers in our country,” said Andrew Eungi Kim, a professor of international studies at Korea University. “It’s a serious problem. If we continue to just conscript South Korean men in their 20s, then the number of soldiers will drop to almost half of what it is now within the next two decades.”

Related: South Korea’s Moon calls for peace with North Korea

Last year, South Korea had roughly 599,000 troops in its armed forces, but the supply of able-bodied males are expected to halve within the next decade. Under the current laws, the number of South Korean citizens eligible for draft is expected to fall to just 225,000 by 2025 — and then 161,000 by 2038.

Part of the problem is that South Korea currently has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, while the nation’s poor job prospects are pushing many young South Koreans abroad. Meanwhile, thousands of male dual citizens give up their South Korean nationality every year to avoid being conscripted into the military, which is notorious for harsh conditions, including hazing and rising suicide rates.

“In the past, there were many reports of extensive verbal and physical abuse … We have suicides happening every year, still,” Andrew Eungi Kim said. “Things are getting better, but it was normal to hear of men who were perfectly normal before entering the military and came out not normal … different than they were before.”

Among soldiers, it’s no secret that serving in the South Korean military can be brutal.

“Say if someone just started, but only a month before you — they’re above you and they have the right to discipline you however they want, whenever they want,” Chun said. “It’s tough. But I also think the biggest reason young people don’t want to go is that it’s such a long time in the prime of your youth to just throw away.”

Military as identity

South Korea’s dwindling army fuels support for conscription of naturalized citizens. But there’s also the principle of fairness — or the idea that forcing naturalized citizens to serve might help them find acceptance as true Koreans.

“Being a South Korean citizen comes with this demand to take on a military identity if you’re a man. … Men in their prime years enter the military, and then they come out with this notion of order and hierarchy and loyalty — and of course, a world without women.”

“Being a South Korean citizen comes with this demand to take on a military identity if you’re a man,” said C. Harrison Kim, a professor of Korean Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. “Men in their prime years enter the military, and then they come out with this notion of order and hierarchy and loyalty — and of course, a world without women.”

Military service is often seen as an integral part of the South Korean male identity. Companies are known to overlook male hires who didn’t serve, including mixed-race South Korean citizens who were only legally included in the draft starting in 2010. Others are publicly shamed for dodging their service.

Yoo Seung-jun, a famous Korean American singer, was unlawfully banned from South Korea for 17 years when he chose not to serve after he obtained US citizenship. Yoo had full legal rights to renounce his Korean citizenship and avoid serving, but by the time the South Korean Supreme Court overturned his entry ban, the damage to his career had already been done.

Related: K-Pop stars are not exempt from military service, says South Korea

More than a decade ago, these kinds of hostilities led Yoon Joo-hee, now 37, to serve in the South Korean military for nearly two years.

Like Yoo Seung-jun, Yoon became a naturalized citizen of another country (Canada) before receiving his draft call from the South Korean military. But he decided to serve out of paranoia. Yoon wanted to work in South Korea, and he was worried that its visa office or future Korean employers might accuse him of gaining Canadian nationality just to avoid military service.

“I thought that it might be an obstacle for me down the road to even get a job or a visa if I didn’t serve. … I decided to just get it over with. It was really tough.”

“I did want to live [in South Korea] and I didn’t want to jeopardize my chances of living here by not answering my draft call. I thought that it might be an obstacle for me down the road to even get a job or a visa if I didn’t serve,” said Yoon, who now works in the South Korean broadcast industry and lives with his parents in Seoul. “I decided to just get it over with. It was really tough.”

At the end of his service, Yoon was forced to choose between his South Korean and Canadian citizenship (after 2011, the law arbitrarily changed so that some dual citizens who served in the South Korean military were allowed to keep both citizenships on a case-by-case basis). He now lives in Seoul under an F4 visa — a special status given to foreigners of Korean descent that allows them to live and work in the country for several years.

It’s unclear what would have happened to Yoon — whose family also currently lives with him in South Korea — if he didn’t answer his draft call.

In 2018, the government decided to bar any former South Korean male citizens under the age of 40 from getting an F4 visa if they did not serve in the military before giving up their South Korean citizenship. That means people like Yoon would have no F4 visa if they didn’t agree to serve when they were still of drafting age.

To some, the proposed system doesn’t make much sense. The problem is twofold: Fewer people might pursue naturalization if they are forced to serve, all while dual citizens will continue to legally leave the country to avoid a draft.

“I think it’s a question of fairness, right? If people want to be a Korean citizen and enjoy all of the benefits that come with it, then military service is a burden they should also have to share,” Yoon said. “But there have to be some incentives. I can’t imagine many people will [pursue naturalization] because, as that plan looks right now, it’s not a good deal at all.”

“I think this plan would definitely discourage people from trying to get citizenship,” Chun agreed. “But clearly, the government might not care.”