Preparing for hurricanes: 3 essential reads

Shoppers find empty bread shelves at a store ahead of the arrival of Hurricane Dorian

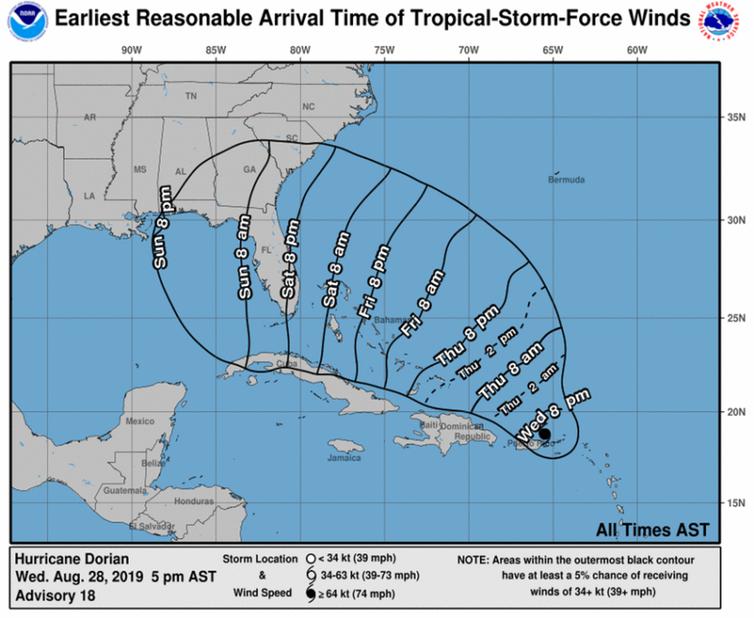

The National Hurricane Center forecast on Aug. 29 that Hurricane Dorian could make landfall this weekend and bring large amounts of rain, strong winds and potential flooding from storm surge.

Florida has declared a state of emergency and residents are preparing for what could be a Category 4 hurricane on the state’s Atlantic coast. Here are three articles from The Conversation’s archive that provide context on how people can prepare for hurricanes.

1. Predicting the path and power

Hurricane Dorian has already moved past Puerto Rico and is expected to gain strength as it travels over the warm Atlantic waters off the coast of Florida. Yet forecasters say there’s a great deal of uncertainty regarding this storm.

Meteorologists Mark Bourassa and Vasu Misra from Florida State University explain how hurricane forecasts are done — using a number of software-based models that generate predictions of where hurricanes will go, and how strong they’ll be from starting conditions, such as wind speeds and ocean temperatures.

Related: Hurricane evacuation of nursing home residents still an unsolved challenge

Aided by observational data from buoys and aircraft flown into developing storms, forecasts for the paths of hurricanes — which are tropical cyclone storm systems that originate in the Atlantic — have improved significantly over the past decade, they write. But that’s not true for hurricane intensity.

“It’s extremely difficult for a model to estimate the maximum wind speed of a tropical cyclone at any given future time,” write Bourassa and Misra. “Small-scale features of tropical cyclones — like sharp gradients in rainfall, surface winds and wave heights within and outside of the tropical cyclones — are not as reliably captured in the forecast models.”

2. When to stay and when to go

Experts recommend heeding evacuation warnings. But how do state officials know when to call for a mandatory evacuation?

Hazard expert Susan Cutter from the University of South Carolina says that there are two measurable factors that can go into the calculation: when sustained tropical force winds are expected to arrive and clearance time, or the amount of time needed for vehicles in an area to reach points of safety.

But in the end, the practice of calling for an evacuation is as much science as it is a skill based on experience — and luck.

“It is hard to predict the path of hurricanes, and even more so the behavior of people in response to them. There is a lot of uncertainty in the projections of both, which is why you often hear emergency managers say better to be safe than sorry,” she writes.

3. The role of social networks

Social sciences researcher Daniel Aldrich wanted to get more insight into when people choose to evacuate and when they don’t.

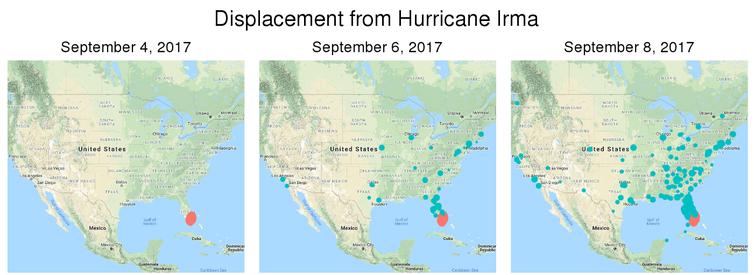

Analyzing social media following disasters, Aldrich found that people with far-reaching social networks — that is, connections beyond their immediate families and close friends — were more likely to evacuate in the days leading up to a hurricane.

By contrast, his research found that social networks more narrowly focused on family and friends were less likely to evacuate before a hurricane.

“This is a critical insight,” Aldrich writes. “People whose immediate, close networks are strong may feel supported and better-prepared to weather the storm.”

Understanding how people use their social networks is important because choosing to stay can create more risk of harm and damage when storms do finally come.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Martin LaMonica is a Deputy Editor atThe Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.