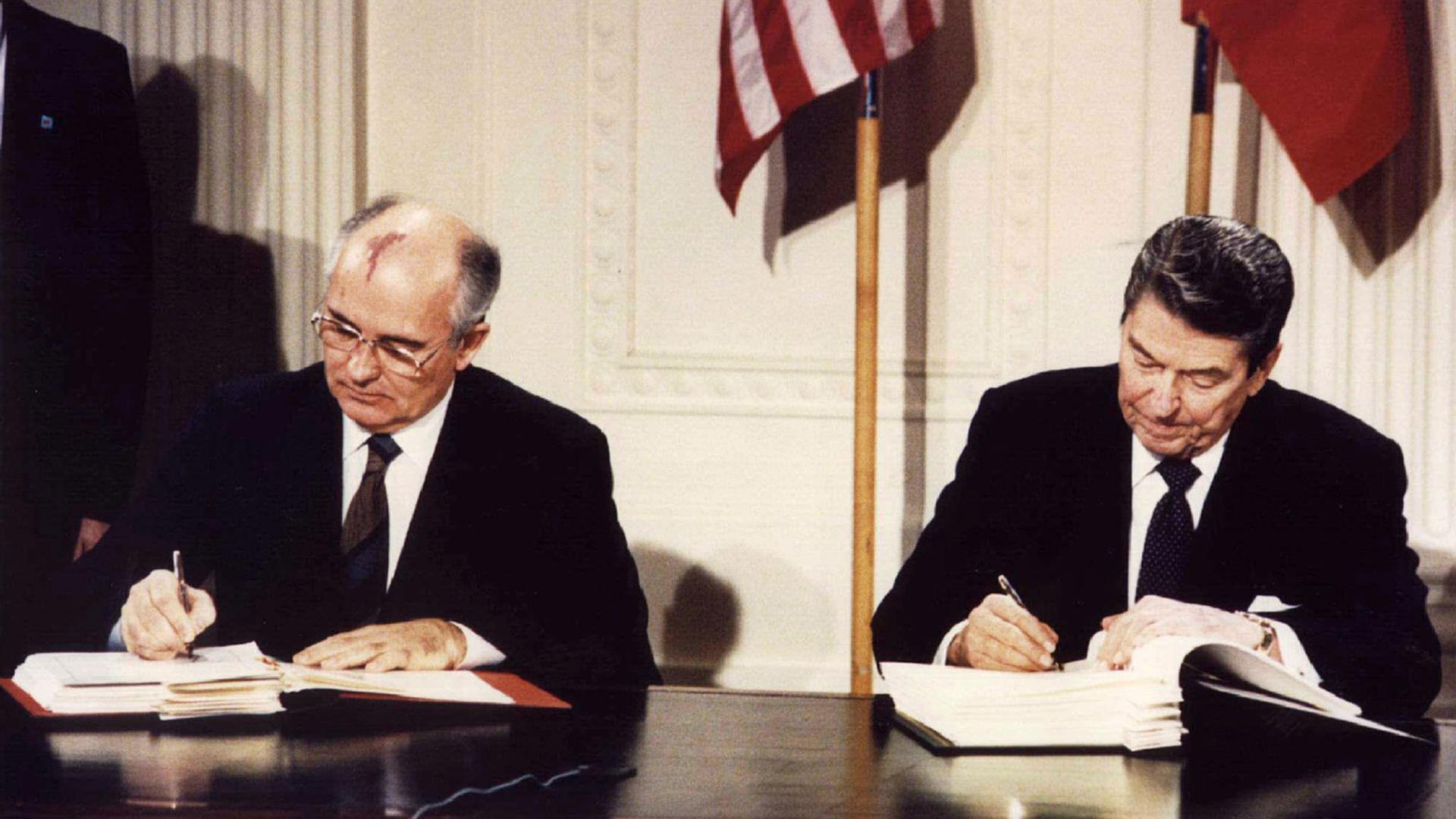

US President Ronald Reagan (right) and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev (left) sign the INF treaty at the White House, on Dec. 8, 1987.

In December 1987, United States President Ronald Reagan hosted Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the East Room of the White House for a ceremony that signaled the changing times.

Reagan, a Cold War hardliner who had labeled the USSR “the Evil Empire” just four years earlier, was all smiles with Gorbachev, the Soviet reformer. Reagan even dusted off a Russian proverb that would come to define the new era in US-Soviet relations:

“Though my pronunciation may give you difficulty,” said Reagan. “The maxim is — doverai no proverai — trust but verify.”

“You repeat that at every meeting,” Gorbachev responded as the crowd erupted in laughter.

With that, the leaders sat down to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty — the latest symbol of growing detente between the Cold War adversaries.

“It was a momentous occasion,” remembers George Shultz, Reagan’s secretary of state from 1982-1988 and a key figure in crafting what would become known as the INF treaty. “Gorbachev was a rockstar kind of guy.”

Shultz, now 98 years old and still active as a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, says the INF deal came about in large part because of a shift in Reagan’s thinking — not toward the Soviet Union, but toward nuclear weapons themselves.

“Reagan thought they were immoral. Where is it written that a man can push a button and kill a million people? That’s God.”

“Reagan thought they were immoral. Where is it written that a man can push a button and kill a million people? That’s God,” Shultz says.

In Gorbachev, Reagan found a Russian partner who also viewed nuclear weapons as essentially unusable, says the Soviet leader’s longtime English translator, Pavel Palazhchenko.

“Gorbachev and Reagan had the goal of arms reduction and they did not allow themselves to be pushed off track,” Palazhchenko says. “They did not allow themselves to be distracted from their goal.”

Palazhchenko had reason to be skeptical. As a Soviet diplomat, Palazchenko had overseen years of failed arms control negotiations with previous Soviet leaders.

“I was a happy man that day,” says Palazhchenko in recalling the INF signing ceremony.

“[It was] definitely a huge step forward. Two great nations, two nuclear superpowers have finally been able to stop the arms race in at least two categories of nuclear weapons.”

“[It was] definitely a huge step forward. Two great nations, two nuclear superpowers have finally been able to stop the arms race in at least two categories of nuclear weapons.”

With the agreement, the US and USSR formally renounced the development and deployment of ground-launched missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.

Of course, the US and USSR were still armed to the teeth. Both still possessed enough nuclear weapons to destroy one another and the rest of the planet.

But Shultz says the INF’s elimination of short- and medium-range arsenals made the world infinitely safer in one critical regard — time.

“Between when they’re fired and when they hit is only about 10 or 11 minutes. So, if you’re trying to do something about it, you don’t have much time,” Shultz says.

“People have somehow now forgotten what happens when a nuclear weapon hits.”

Nuke for nuke

The crisis around shortened impact times started in the mid-1970s. The Soviet Union had developed a new class of medium-range nuclear missiles — the so-called SS20s — that were both mobile and capable of striking targets in Western Europe with little warning.

“To be more specific, they were targeted againsttargets in my country,” recalled Helmut Schmidt, the former chancellor of West Germany in an interview with WGBH radio in 1987.

Faced with the SS20 threat, Schmidt pushed the US to match the Soviets by deploying its own short-range nukes in Europe.

“Under the compelling threat of seeing medium-range weapons coming up over the horizon, threatening a number of Russian cities, they would negotiate,” said Schmidt at the time.

The only problem? The American weapons didn’t exist.

It took a few years but by the early 1980s, the US was producing its own intermediate-range weapon, the Pershing II, which the US and its NATO allies threatened to deploy in West Germany — as close as possible to the communist bloc borders — in 1984.

“Pershing II’s extended range allows NATO to counter the unilateral threat of the SS20 missile by holding at risk targets in the Soviet Union,” declared a US Army promotional video touting “this latest addition to the Pershing family” of missiles.

Palazhchenko, Gorbachev’s aide, says the threat proved convincing to Soviet hardliners who — up until that point — saw little point in negotiating with the US.

Now they understood time was working against the Soviets, too.

“When the Americans completed their program of deployment, then the situation became at least on the face of it quite different,” Palazhchenko says. “Americans have ballistic missiles that have a flight time to Moscow of less than 10 minutes.”

Beware of ‘Euroshima’

The shortened impact from both sides magnified the risks of what some called a potential “Euroshima.”

What if something went wrong? Or one side misread the other’s intentions?

Previously, the Cold War threat consisted of missiles lobbed across oceans. Deadly, for sure. But they also provided a window — an estimated 20-30 minutes — to negotiate, verify an attack, or even declare a false alarm.

Related: The Man Who Saved the World

By contrast, these new short- and medium-range missiles just had to clear the Iron Curtain and … boom.

Fear of stumbling into nuclear Armageddon gripped the European public — including a young West German singer named Gabriele Kerner. Performing under her stage name Nena, her band would go on to record an anti-Cold War anthem called “99 Luftballons.”

The song imagines balloons drifting accidentally into enemy airspace — triggering an accidental world war with “no place for winners”in a “the world left in ruins.”

It wasn’t hard for the European public to make the connection between the lyrics and the INF standoff unfolding before their eyes.

This was at the height of the antinuclear movement in Europe. Thousands marched against their governments in opposition to the US missiles — a factor that increasingly influenced Washington’s own decision-making.

“We were negotiating not only with the Soviets but the European public,” recalled Shultz.

Indeed, public opposition — and a desire to claim the moral high ground — drove President Reagan to embrace a concept called the “zero option.”

The idea? That when it came to negotiating over the intermediate- and short-range nukes, Reagan wouldn’t just push for the US and USSR to limit their arsenals. They’d demand both sides give up everything.

Critical to selling the idea was Reagan’s favorite Russian maxim — trust but verify.

“The INF treaty contains in it the most clear verification provisions. Onsite inspections!”Shultz says.“People said we could never get that but we did.”

Over the next three years, inspectors observed as both sides destroyed their arsenals — over 800 missiles by the US and nearly double that from the Soviet side.

Viktor Litovkin, a military journalist who covered the events for the daily Izvestia newspaper, remembers watching as Soviet engineers and military officers carried out the treaty’s agreements — destroying missile after missile as they wept.

“I understood why,” Litovkin says. “It was their life’s work and they were experiencing every parent’s worst nightmare.”

They were outliving their children.

INF 1987-2019 (RIP)

Today, the Trump administration argues the INF treaty has outlived its use.

Last October, President Donald Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, traveled to Moscow to deliver the news: The US intended to leave the INF agreement amid long-standing US accusations that Russia was violating the treaty.

Related: Gorbechev criticizes US withdrawal from INF Treaty

The reality, said Bolton, was that the INF was “outmoded” while other countries that have immediate range weapons — like China — weren’t part of the agreement.

“Under that view, exactly one country was constrained by the INF treaty — the United States,” Bolton said.

Russian President Vladimir Putin soon followed suit — announcing that Russia, too, was pulling out of the deal.

Barring a last-minute reprieve, the INF treaty expires Aug. 2. Both sides already vow to develop a new generation of short- and intermediate-range weapons.

A new arms race?

All of this has left Europe, once again, in the middle of a potential new arms race, even as tomorrow’s weapons mean shorter warning times.

“We will miss the INF when it’s gone. … We are going back to the Cold War.”

“We will miss the INF when it’s gone,” says Ulrich Kuhn, an arms control expert at the Institute of Peace Research and Security at the University of Hamburg. “We are going back to the Cold War.”

Related: How Trump’s exit from a Cold War-era treaty could trigger a 3-way arms race

Kuhn points to new divisions in Europe over how to best respond to Russian nuclear deployments.

“We might see a situation where Central and Eastern European states say we really need to push back against the Russians and other Europeans saying we don’t want that,” Kuhn says.

“That could put NATO in serious trouble.”

Meanwhile, nearly 30 years after the initial INF treaty signing, the diplomats who crafted the agreement worry today’s politicians are too cavalier about the threat posed by nuclear weapons.

“When something like the INF goes down the drain almost like nothing, it shows you the degree to which people have forgotten the power of these weapons.”

“When something like the INF goes down the drain almost like nothing, it shows you the degree to which people have forgotten the power of these weapons,” Shultz says.

“We are unfortunately moving toward a situation where we might — maybe within a few years — have no arms control, no mutual verification and no mutual restraint,” warns Gorbachev’s aide, Palazhchenko.

“The INF was a success story,” he adds. “And there aren’t many success stories in US-Soviet and US-Russia relations.”

Editor’s note: This story was produced with funding from N-Square Collaborative.

We’ve partnered with a video game company to let our readers put themselves in the shoes of someone who deals with nuclear weapons. Try the game for yourself at nucleardecisions.org.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?