A raging TB epidemic in Papua New Guinea threatens to destabilize the entire Asia Pacific

A nurse and a tuberculosis patient take in some air at the TB ward at the Kerema District Hospital, Kerema, Papua New Guinea. TB is highly contagious and deadly if not treated.

In a stark, white hospital room in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, a man named Keith spends long days quarantined in an entire wing.

Keith, in his 50s and wears a grubby T-shirt and pants and sports a long scraggly beard, is highly contagious with a rare strain of extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis.

“I’m happy I’m here,” Keith says. “I have run away [from the hospital] many times, but now I know that it is a good thing that I am here. I need to take my medication so I can get better.”

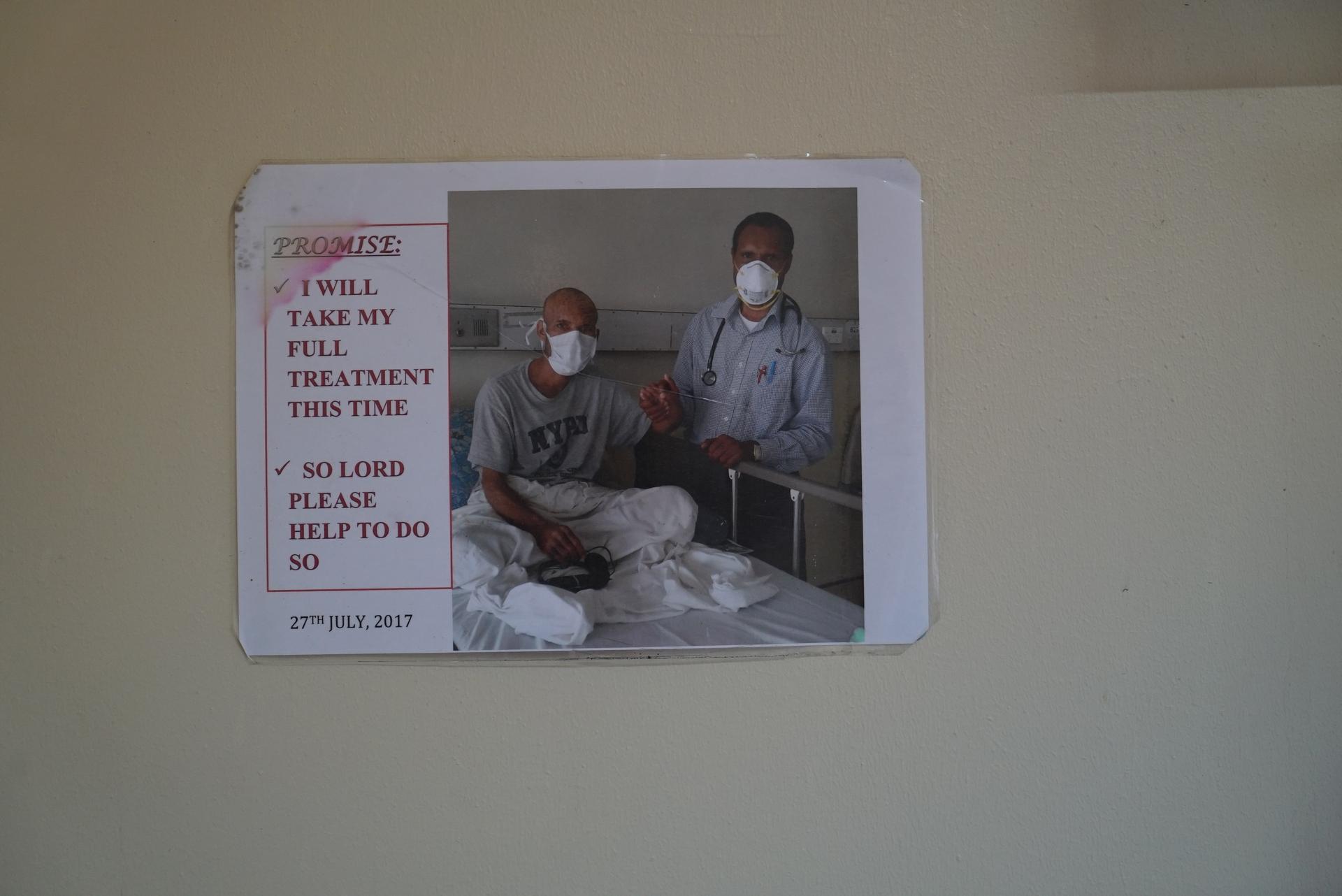

Homeless for many years, Keith doesn’t know his last name. His tattered sneakers sit neatly by the door. A poster on the wall above his sink shows a shaven Keith holding hands with Dr. Rendi Moke, the TB specialist at Port Moresby General Hospital — as if they are making a pact. It reads: “Promise: I will take my full treatment this time. So Lord, please help to do so.”

On the opposite wall, there is a simple wooden cross.

“We have to keep him isolated, we don’t have a choice. And that’s not a great solution when you desperately need hospital beds. I’m worried there will be more like him out there, who we don’t even know about.”

“We have to keep him isolated, we don’t have a choice,” Moke said. “And that’s not a great solution when you desperately need hospital beds. I’m worried there will be more like him out there, who we don’t even know about. We’re very keen to reduce our default rates [patients who don’t finish treatment] and increase our capacity to treat others and perform more outreach work. “But,” he adds, “to do that we need resources and manpower. And we have neither.”

In Papua New Guinea, a TB epidemic threatens to turn into a disaster that could destabilize the Asia Pacific region. Situated about 90 miles from Australia in the Pacific Ocean, the island nation sees more than 100 cases of TB every day.

Of these cases, five are drug-resistant strains, and 10 people will die, according to World Health Organization figures. Yet, in a nation where more than one-third of the population is illiterate, these figures grossly underestimate the actual number of TB cases due to underreporting. Additionally, 86% of the country’s 8 million citizens live in rural areas with little or no access to health care, further obscuring the numbers.

The government now faces a herculean task to battle the epidemic that has plagued the country. It shares the island with the separate nation of Papua, Indonesia’s easternmost province, which faces a similar struggle against TB. And Australia, a close neighbor, also has cause for concern: The bacterial disease that attacks the lungs is highly contagious, expensive to treat and is rapidly developing a resistance to drugs.

The country offers a grim textbook case of how education and infrastructure impact health care: The government has neither the finances nor the resources to tackle TB as an increasingly insurmountable health crisis.

Related: Hospitals on Venezuela border ‘turning into cemeteries for migrants’

“This is World War III. …We are working incredibly hard to fight this, but we need new drugs that we don’t have. We need resources that we don’t have. And whatever we don’t do now, will come back to haunt us in the future.”

“This is World War III,” said Paison Dakulala, deputy secretary of the National Health Services of Papua New Guinea. “We are working incredibly hard to fight this, but we need new drugs that we don’t have. We need resources that we don’t have. And whatever we don’t do now will come back to haunt us in the future.”

A report published in May by the Economist Intelligence Unit warned of the consequences of failing to act against drug-resistant TB (DR-TB), calling the current response a “global failure.”

In the same month, the United Nations issued an urgent warning about the growing peril of drug-resistant infections. The report stated at least 700,000 people die worldwide each year due to drug-resistant diseases; 230,000 of those die from multidrug-resistant TB.

According to the WHO, 10 million new TB cases appeared globally in 2017 alone (though TB rates have fallen worldwide). That same year, it killed 1.6 million people, making TB the world’s deadliest infectious disease. And places like Papua New Guinea are seeing an uptick in infection rates — particularly in multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and the even more feared drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB).

This grim trend is exportable to neighboring countries.

Related: Leprosy in India is back, but it never really went away

In Papua New Guinea, TB is the leading cause of hospitalization and death. It presents a unique challenge for charities — such as Doctors Without Borders — that have established services in the country to help manage the crisis.

Paul Aia, WHO’s TB program manager, explains the difficulty in diagnosing and treating patients in a country with poor infrastructure.

“One patient received his first bout of medication, but then it took two days to track [him] down to administer the next set of drugs,” he said.

Some patients get diagnosed, and then start — but don’t finish — their drug course. That’s exactly the type of behavior that increases the likelihood of drug-resistant TB.

Obstacles and roadblocks

Many patients can only reach their nearest makeshift hospital by boat — and children have reportedly died en route to treatment after canoes capsize in choppy seas, according to aid workers.

Port Moresby, the capital, is not connected to other major towns by road, and many of the villages in the highlands can only be reached by foot or small aircraft, which is astronomically expensive. Frequent mobile cell service outages render communication a daily struggle. Several mountainous tribes still have little or no contact with the outside world.

“It is so hard for me to do this journey so often. … But what choice do I have? I felt so ill before I started. I was dizzy, I had to stop working, and so I couldn’t earn money to feed my children. I still have so long to go before I finish my medication, and I constantly have to miss work to come and get it. But if I don’t take it, I will most likely die, and my children will have no mother.”

In the town of Kerema, a small hospital staffed mostly by Doctors Without Borders organizes medical checks in nearby villages. One morning, they head to the village of Meii on a small wooden boat. Kari Dusty, an MDR-TB patient, traveled back to Kerema with them to pick up her medication, which she has to do every few days because her drugs require refrigeration. The mother of five is six months into her two-year-long treatment.

“It is so hard for me to do this journey so often,” she told The World through a nurse, who acted as a translator. “But what choice do I have? I felt so ill before I started. I was dizzy, I had to stop working, and so I couldn’t earn money to feed my children. I still have so long to go before I finish my medication, and I constantly have to miss work to come and get it. But if I don’t take it, I will most likely die, and my children will have no mother.”

“It is not as simple as educating people about TB. … We are coming up against traditions, culture, illiteracy, no proper transport, and no money to fund the expensive DR-TB treatment.”

With approximately 850 languages spoken in Papua New Guinea, TB education and treatment relies on educators who can speak local languages and dialects like Tok Pisin, a Creole language, and Hiri Motu, a trading language.

“It is not as simple as educating people about TB,” says Lungten Wangchuk, a Papua New Guinea-based TB medical officer with WHO. “We are coming up against traditions, culture, illiteracy, no proper transport, and no money to fund the expensive DR-TB treatment.”

Ancestral traditions, including witchcraft, continue to thrive in the predominantly Christian nation, and citizens hold strong superstitions about TB as a curse. Some patients will see a village shaman for treatment rather than accept the prescribed medicine. The government pledged $2.9 million in education programs to dispel witchcraft beliefs, but the UN estimates around 200 witch killings in the country every year.

“We have heard many cases of TB patients being stoned to death,” Aia added.

As one of the world’s poorest countries — 37% live below the poverty line — those afflicted by TB must use limited resources, including money and time, to seek help. And TB can’t wait for its patients. Treatment can take up to nine months, and that’s only one-third of the time it takes to address multiple-drug-resistant TB, which can run 24 months.

Related: Trudeau apologizes for mistreatment of Inuit during tuberculosis epidemic

According to WHO estimates, the median cost for treating drug-susceptible TB is $1,253 per person, per course; the cost for treating MDR-TB rises to $9,529 per person, per course. Papua New Guinea provides patients with medication free of charge with support from Australia and the World Bank — but this still doesn’t ensure patients complete their course.

As of 2017, doctors saw about 2,000 new cases of drug-resistant TB in Papua New Guinea and they predict it will become the dominant strain of TB within a decade.

“The situation will escalate,” Dakulala cautions. “And we will see more and more cases of multiple and extensively drug-resistant TB.”

Papua New Guinea, along with Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and China all face challenges as countries classified with a “high burden” of TB, with Somalia, Peru and Central Asian countries particularly struggling against MDR-TB.

The disease costs Papua New Guinea approximately $23.5 million annually in loss of workforce and productivity. Investing in TB control yields around a $40 return for every $1 spent.

“We’ve seen a huge rise in MDR-TB cases, especially in children,” he continues, as he walks down the small corridor of the newly opened TB building, funded by the Malaysian Association of Papua New Guinea.

In the pediatric wing, rows of beds line the room, each occupied by a small child.

Moke points to one child who is alone, unlike the other children who are accompanied by their mothers. The 11-year-old boy is completely emaciated, staring blankly at the ceiling above him, a tangle of skin and bones. The boy comes from a settlement just outside of Port Moresby, two bus rides away.

“This child has TB in his brain. His mother cannot come to keep him company as she has five other children. He will be here until he dies.”

“This child has TB in his brain,” Moke explained. “His mother cannot come to keep him company as she has five other children. He will be here until he dies.”

Globally, pediatric TB makes up 10-11% of all TB cases. In Papua New Guinea, the figure is 27%.

Those living with HIV, which weakens the immune system, also run a greater risk of TB infection. Latent TB is more likely to advance to TB disease in people with HIV than in those without — and TB can also cause HIV symptoms to worsen.

In 2017, 32% of AIDS deaths globally related to TB, and nearly one million people living with HIV fell ill with TB that same year. Papua New Guinea has one of the most serious HIV/AIDS epidemics in the Pacific — 95% of cases in the region are reported in just this one country. Infection rates increased by 4% between 2014 and 2016.

Related: World Health Organization warns global ‘tuberculosis epidemic’ is larger than previously thought

Small victories

Papua New Guinea has won some battles, though.

Dakulala proudly refers to success stories on the island of Daru, which was considered a TB “hotspot” in 2016. In 2017, WHO declared a drug-resistant-TB outbreak under control, largely due to resources, medicines and vaccine tents provided by Australia, the World Bank, and the Global Fund.

However, Papua New Guinea officials fear funding will dry up in 2020 when Global Fund monies are finished. There is no guarantee of renewal.

A worried Australian health official, who wished to remain anonymous, confided the reason Australia invests so much in tackling TB in Papua New Guinea (more than $500 million AUD in 2018-19) is because of youth migration to Australia.

“Multidrug-resistant TB clearly poses a very significant risk to us,” the official said. “The cost of addressing that strain is 200 times the cost of treating TB, so it makes sense for us to invest in treatments. There is a clear human need to address this epidemic. There is just [3.1 miles] separating Australia and Papua New Guinea [referring to Boigu Island, part of Queensland] and so the regional health security issue is imperative.”

The Australian government expressed commitment to addressing health security challenges in the Indo-Pacific region by preparing for infectious disease outbreaks, according to a spokesperson for the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, speaking to The World.

“In Papua New Guinea’s Western Province, Australia’s support has led to 99% of people completing their TB treatment (up from 65% in 2014), helping to reduce the emergence of drug-resistant strains,” he said.

Late last year, a $15 million grant was secured by the Papua New Guinea government from the World Bank for a new emergency TB project and Australia has committed $15 million as well.

For Dakulala, it’s a vital financial lifeline for his country.

“We need help,” he said. “We cannot fight this alone.”