This submarine’s historic tour under Thwaites Glacier will help scientists predict sea level rise

The Hugin autonomous submarine nicknamed Ran after the Norse goddess makes a dive into the ocean after being loading off of the Nathaniel B. Palmer research vessel.

Oceanographer Anna Wåhlin paced across the bridge of the Nathaniel B. Palmer icebreaker like a nervous parent waiting for a teenager out past curfew.

The fiery orange submarine, which she named Ran after the Norse goddess of the sea, hadn’t yet resurfaced from its first mission in the watery depths around the face of West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier.

“She’s a very temperamental lady,” Wåhlin said of the $3.6 million, unmanned submarine, while peering through her binoculars on an overcast March day.

Ran was late. Wåhlin wasn’t worried about the submarine disappearing, but this was Ran’s first season in polar waters, and there were a bunch of kinks to work out.

Wåhlin, an oceanographer at Sweden’s University of Gothenburg, was one of the roughly two dozen scientists on a pioneering scientific expedition to Thwaites Glacier this past winter. The two-month cruise aboard the Palmer was the beginning of a five-year, $50 million international collaboration to better understand the plight of Thwaites. Scientists believe the massive glacier is teetering on the brink of collapse, though just how fast that could happen remains an open question.

Florida-sized Thwaites Glacier holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by 2 feet. If the glacier collapses, it could destabilize a portion of West Antarctica that would, in turn, raise sea levels by about 11 feet.

That would spell disaster for coastal cities from Miami to Mumbai, which would be inundated by floods.

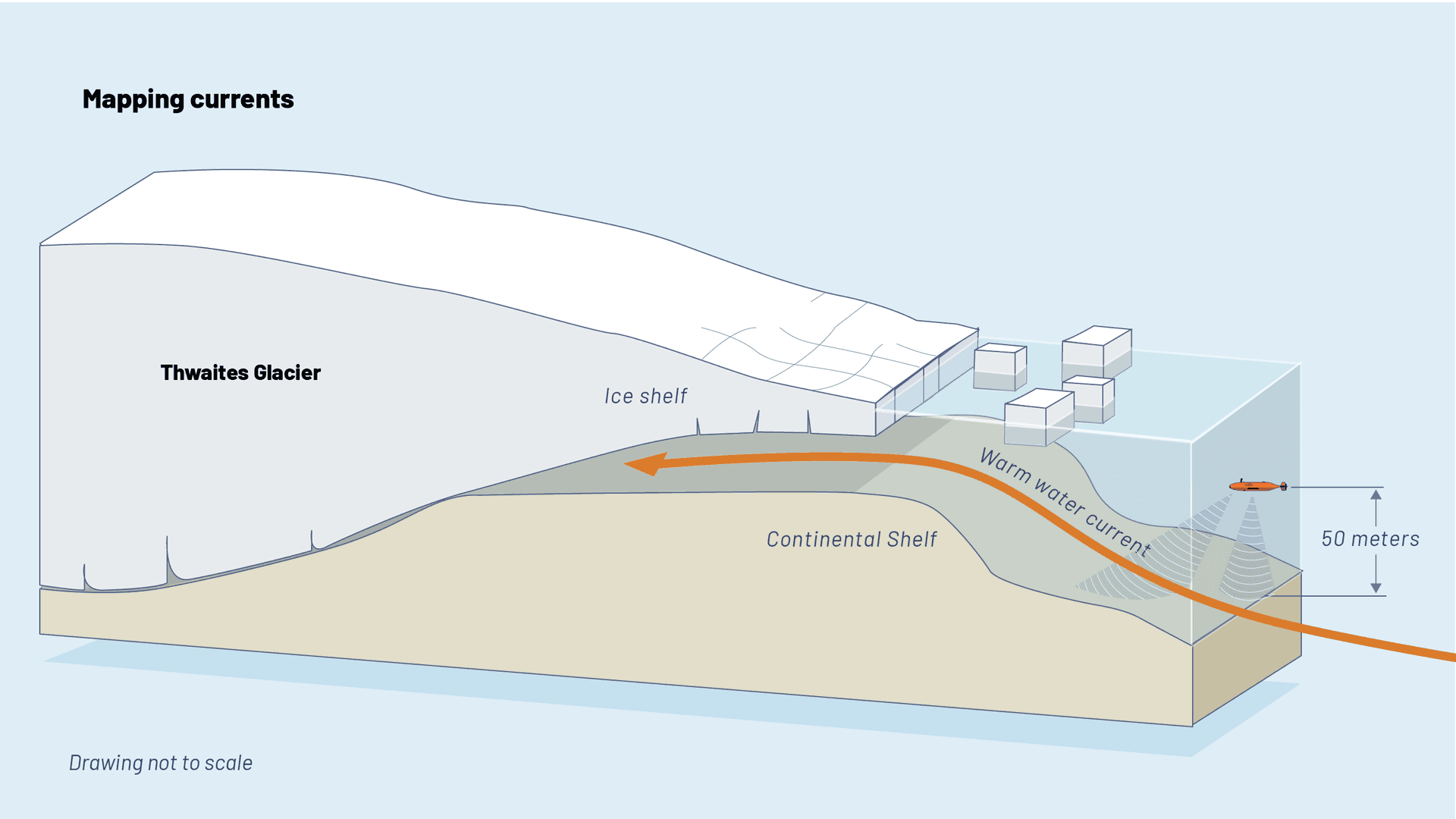

Ground zero for this slow-moving catastrophe is the glacier’s edge, where land-based ice juts out into the Amundsen Sea. Warm water is thought to be melting the underside of this roughly 75-mile ice shelf, but the area is as mysterious as it is consequential.

“We know more about the moon than this particular part of Earth,” Wåhlin said.

Scientists think changing wind patterns are pushing a mass of middepth warm water, called circumpolar deepwater, up from the deep ocean and onto the continental shelf in front of Antarctica and toward Thwaites. But no scientific instrument has ever been underneath the ice shelf to study it.

That’s why Wåhlin worked for seven years to get a Hugin submarine, a 25-foot, torpedo-shaped autonomous underwater vehicle packed with oceanographic sensors.

“This was the dream, Thwaites and the West Antarctic Ice Shelf,” Wåhlin said. “We made this case when we applied for the money; we said that it’s the only way to explore under floating ice shelves.”

Advances in satellite imagery over the past few decades mean scientists can estimate how much ice Thwaites is losing — nearly 80 gigatons a year, a six-fold increase from 25 years ago.

But projecting future melt rates, and predicting whether Thwaites will trigger a runaway collapse, is nearly impossible without on-the-ground data.

“We’re not sure yet what is the ‘black swan,’ the absolute worst thing that could happen at Thwaites,” said Richard Alley, a Penn State University glaciologist.

Two often-cited modeling studies published in recent years (here and here) suggest a full collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could come within 250 years. But Alley cautions that shouldn’t be considered a “worst-case” scenario.

“We’re really hopeful that this five-year research collaboration will give us a lot of insight,” Alley said.

Before now, no ship had ever sailed to the fast-flowing central part of Thwaites. Scientists had never measured the warm layer of water directly in front of it the glacier, so they didn’t know how fast it was flowing, how far it reached under the ice shelf, or even how thick the ice was.

The little orange autonomous submarine, paired with sonar equipment and oceanographic instruments based on the larger 300-foot research vessel, will start to answer those questions.

Wåhlin’s ‘wayward child’

The factory name for the Kongsberg-built submarine is Hugin, but Wåhlin, just the third woman in Sweden to earn a PhD in oceanography, christened it Ran after the Norse goddess as “a little bit of a poke to the gender imbalance that we have in physical oceanography.”

Wåhlin said as recently as last summer, she was the only woman at an AUV conference. She’s fought to build the networks in her field that she felt were ready-made for men, and now says she never turns down a request for mentorship from a female student.

“I don’t do it because I favor women or anything; it’s because I think it’s good for science. Historically, we have only used maximum 50% of the pool of good scientists, and I want to make sure that we use 100% in the future; that is good for science,” Wåhlin said.

Wåhlin, who went on her first research cruise to the West Antarctic Ice Sheet more than a decade ago, says she’s driven by a long-standing desire to know how the world around her works.

“I wonder, I really wonder, what is going on?” Wåhlin said. “It’s curiosity, not fear or anything else.”

Even as a little girl, she was enraptured by the crabs she saw underwater when her parents took her and her two sisters sailing off the west coast of Sweden.

“If you sit near the beach and suddenly focus your eyes on what’s underneath the water surface, then that is very, very fascinating,” Wåhlin said. “And I never let go of that fascination.”

In some ways, Ran is an extension of that. Throughout the Antarctic voyage, the running joke aboard the Palmer was that Ran was Wåhlin’s wayward child — always running late, hard to communicate with, doing the unexpected.

The AUV is packed with 19 sensors that will measure ocean temperature, salinity and velocity to reveal how much warm water is reaching Thwaites and how much meltwater is seeping out.

Sonars pointing both upward and downward will give scientists and geophysicists on the ship a highly detailed view of the underside of the ice shelf and the top of the seafloor.

This winter’s expedition was a first Antarctic test mission for Wåhlin and her submarine, and the goal was simply to master deploying and recovering the AUV in ever-changing Antarctic conditions.

“It is a high-tech instrument, but it has to be handled by low-tech things on the ship,” Wåhlin said.

The hurdles Wåhlin and her five-person team encountered underscore how difficult it is to do anything in Antarctica.

Big waves made it a challenge to wrangle the two-ton submarine with small, inflatable Zodiac boats to lead it back to Palmer. Likewise, lifting the sub back up onto deck — with a winch wire and metal A-frame — was tough with wind and waves rocking the ship.

In early missions the submarine wouldn’t dive, so Wåhlin had to adjust its buoyancy.

And because sea ice can form inches thick overnight in the Amundsen Sea, Wåhlin programmed the sub to stay away from newly formed ice and wait for new instructions on where to resurface to avoid damage. About three weeks into the trip, Ran had to skip a key test mission so it looked like the goal of sending the sub under the ice would be postponed until the next expedition, in two years. Instead, Wåhlin would focus on studying the warm water circulating in front of the glacier.

A ‘little tour underneath Thwaites’

After a month at sea and several test deployments, Wåhlin got her chance to send Ran on a mission in front of the gently sloping face of the Thwaites ice shelf.

She programmed the sub to follow two deep troughs, trenches at just the right depth to funnel the midcolumn layer of warm water thought to be melting the ice shelf toward the glacier’s face.

“The troughs, they are the places where warm water accesses the ice shelf, so we think there will be a current here with warm water that runs underneath Thwaites,” Wåhlin said. “She’s measuring it as we speak.”

After 13 hours in the water, Wåhlin spotted a flash of orange in the distance. Ran was back.

“We actually took a little tour underneath Thwaites,” Wåhlin revealed with a mischievous grin from her perch by the windows at the front of the ship’s bridge. “We didn’t want to tell anyone beforehand, but we have done it now.”

“Historic,” she said, smiling broadly. “I just wish that everyone gets to feel this feeling once in a lifetime.”

Wåhlin rushed to the back deck where the rest of her team was hosing the saltwater off of Ran and downloading the historic data she’d just collected. The words “good luck,” which someone had scrawled on the sub’s surface in mud, were still intact.

Wåhlin high-fived Aleksandra Mazur, who was thrilled that her mentor just added another first to her name.

“She was the first woman to send [an AUV] under an ice shelf!” Mazur said later.

Mazur, a University of Gothenburg colleague and former student of Wåhlin’s, had worked on Ran’s earliest test runs in Swedish fjords last summer. The day Ran finally went under Thwaites, Mazur said she felt like a polar explorer.

“It’s not often to be in a place that no one has ever been before, and do things that no one has ever done before. After all these years, you sacrifice for studying and doing research, and it’s like a huge accomplishment. I’m just so happy.”

Eliminating uncertainty is the goal

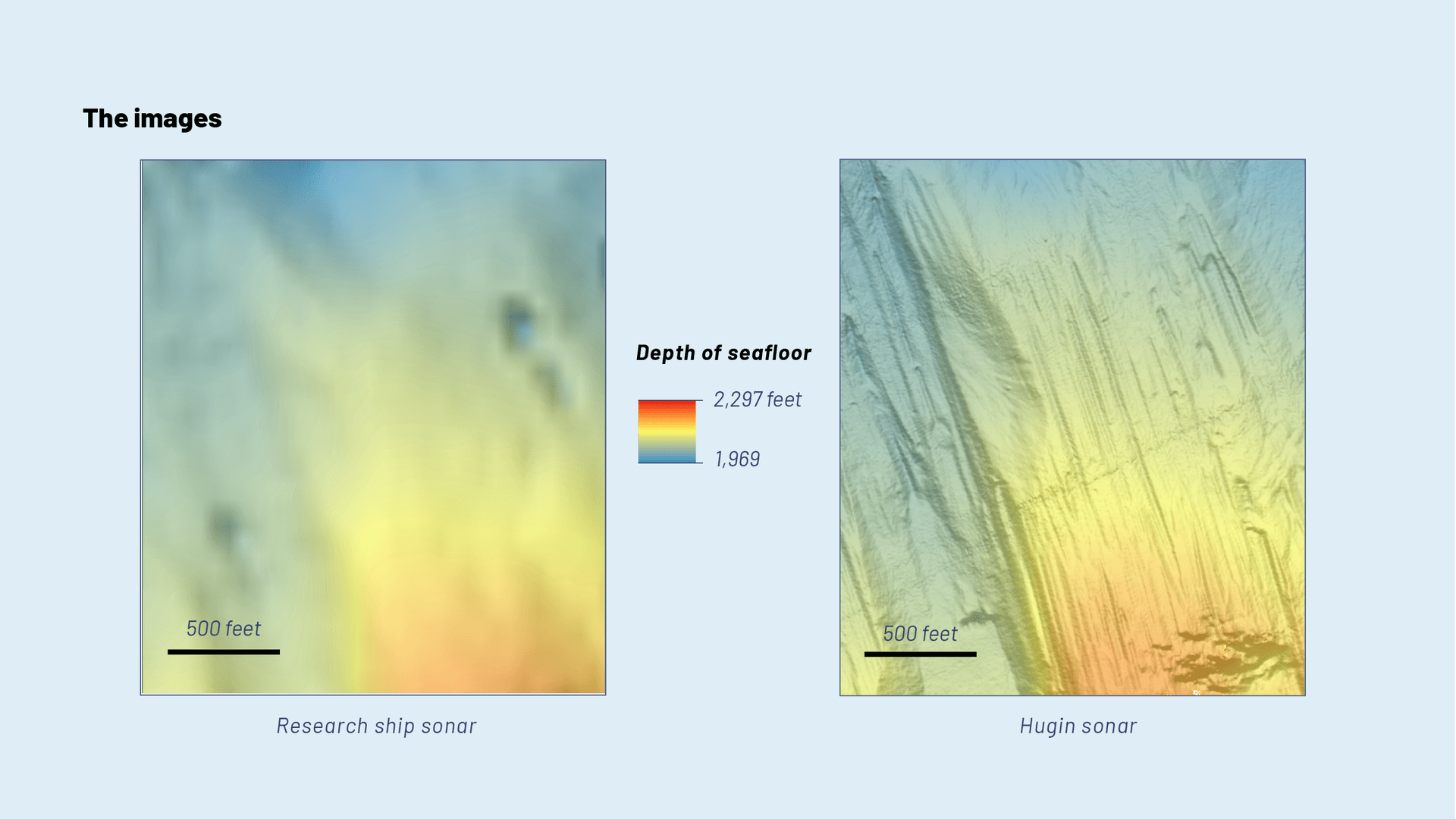

The next day, half the scientists on this ship crowded in front of a computer to marvel at the superhigh-resolution images of the seafloor Ran recorded — they could hold hints about the glacier’s past and future.

“It’s like I’ve been blind all my life, and now, I’ve put on glasses and I can see every individual leaf on the tree,” University of Alabama sedimentologist Becky Minzoni said of the black-and-white images showing marks like tank tracks on the seafloor.

They revealed much finer detail than the ship-based sonar that Minzoni and the geophysicists on the ship had been using to map the seafloor and identify the best places to collect sediment samples. “It’s beautiful,” Minzoni said.

Wåhlin was happy with the readings on temperature, salinity, oxygen and water velocity that Ran recorded, as well as the water samples she collected under the ice shelf.

“No one has ever seen that kind of data before,” Wåhlin said.

For the first time, scientists on the Palmer found and measured the warm water they’d suspected was melting the fast-flowing, central portion of Thwaites.

Using data from Ran’s two-mile trip under the ice shelf, Wåhlin will be able to estimate how much of that warm water reached the ice and trace exactly where it came from.

This data will eventually help improve sea level rise models, the ultimate goal of the five-year international Thwaites research collaboration.

“I think the big takeaway here is not new alarm, or that we all must panic; it’s that we have more data so we can have more reliable estimates for the future,” Wåhlin said.

Right now, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates sea levels could increase anywhere between 8 inches and 2.7 feet by 2100. That’s a huge range, and the entire gap of uncertainty could be filled in just by Thwaites.

For Wåhlin, eliminating that uncertainty is the ultimate goal.

“We have only this one planet that we are living on,” Wåhlin said. “I think it’s fair to say that we should understand what happens, and what goes on, and what we can expect in the future.”

This is the second in a series of deep dives into the science and people of the Nathaniel B. Palmer’s 2019 voyage to Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica. Listen Mondays on The World and check back online through May and June to learn what scientists found as they studied the sea that’s melting this Florida-sized piece of ice. Follow us on Instagram for videos, quizzes and more photos from Thwaites.

Produced by Steven Davy, David Evans, Alex Newman, Anna Pratt and Peter Thomson.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?