Nukes? What nukes? US military’s ‘neither confirm nor deny’ policy complicates activists’ trial

The Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine USS Maryland Gold crew returns to homeport at Kings Bay Naval Base, Georgia, following a strategic deterrence patrol on Feb. 5, 2019. The boat is one of five ballistic missile submarines stationed at the base and is capable of carrying up to 20 submarine-launched ballistic missiles with multiple warheads.

On an April night in 2018, a group of seven Catholic activists arrived at Kings Bay, a nuclear weapons base on Georgia’s balmy southeastern coast.

The base is located near the seaside town of St. Marys, where school children often ride ferries on biodiversity field trips to a nearby island. It’s barely visible beyond its brick entry gates — a thick pine forest hides the submarines that are capable of traveling through international waters to launch nuclear-tipped missiles at adversaries thousands of miles away.

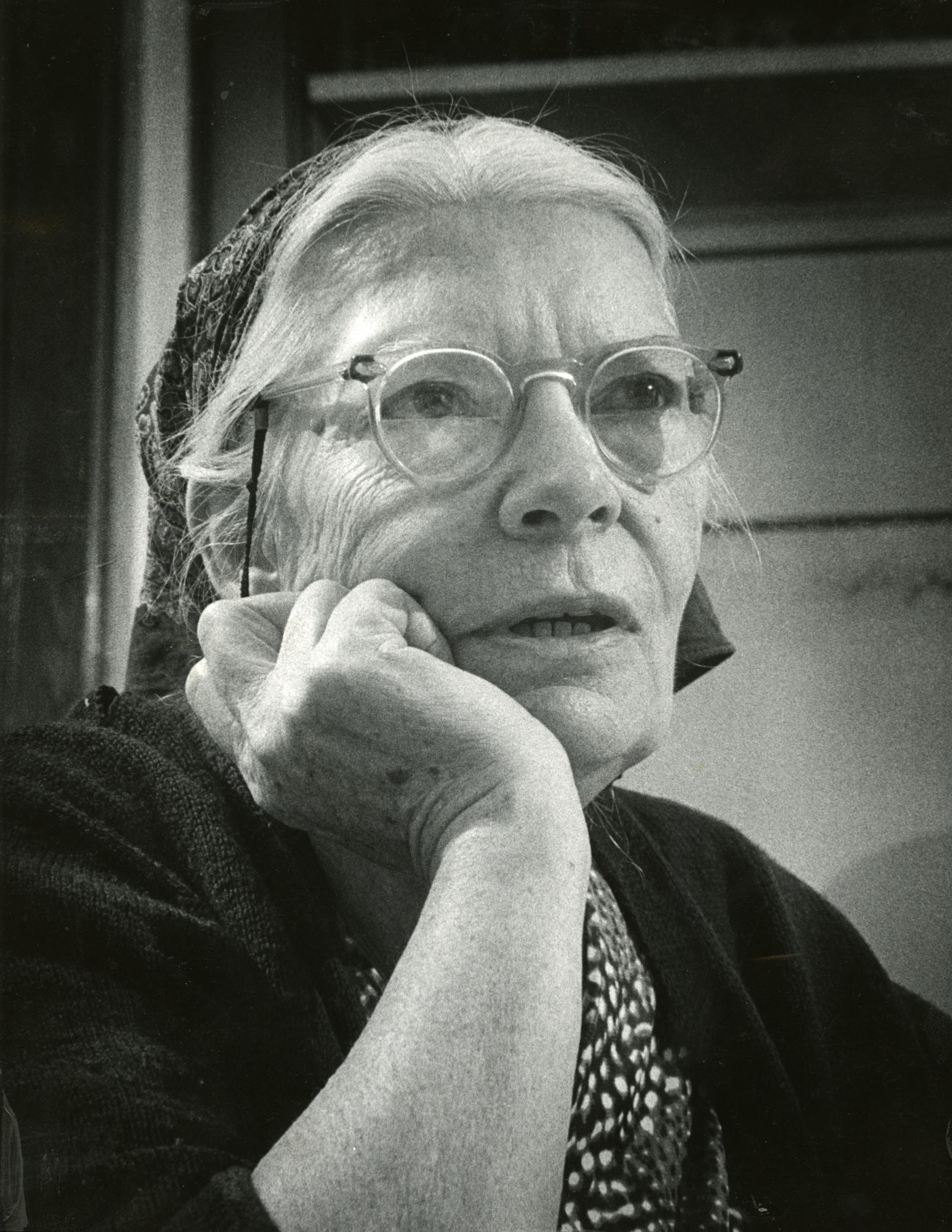

That April night, the group, including Martha Hennessey,the granddaughter of Catholic social justice icon Dorothy Day, arrived at the base armed with hammers, paint and baby bottles of their own blood. They cut through a padlock on a perimeter fence gate and used the blood and paint to write a message on the base’s sidewalk:

“May love disarm us all.”

The group spent several hours on the base, even as an automated loudspeaker blared: “This is a restricted area. Use of deadly force is authorized.”

Members of the group, who call themselves the Kings Bay Plowshares 7, in reference to a Biblical command to “beat swords into plowshares,” were well aware they could face up to 25 years behind bars for their trespass. Elizabeth McAlister, 79, the oldest member of the group, already had one prison stint under her belt for her activism.

Their actions and prosecution reveal a mix of alarm and approval that Americans today feel about the US’ mighty nuclear arsenal.

“May love disarm us all.”

Before Marines were tipped off to the overnight intruders and rushed to arrest them, the activists left behind a copy of “The Doomsday Machine” by Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg.

The group, charged with three felonies and a misdemeanor, would later tell a judge their activism was a desperate attempt to engage in “prophetic action to raise the consciousness of society” about the “immorality” of nuclear weapons.

There was just one problem: Kings Bay doesn’t hold nuclear weapons. Not officially, at least.

‘Cannot confirm or deny’

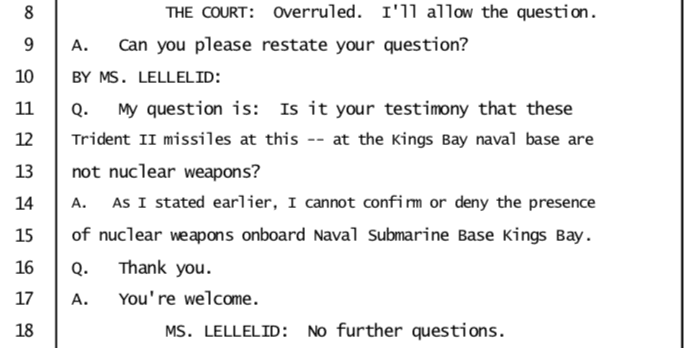

“I cannot confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons onboard Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay.”

“I cannot confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons onboard Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay,” former base Captain Brian Lepine told a defense attorney for the activists at a November 2018 hearing, which covered a defense motion to dismiss charges against the activists under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Lepine did say, however, that protesters tend to show up each year at the base to mark the anniversaries of the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, according to court documents reviewed by The World.

The captain’s ambiguity about the sole purpose of the 17,000-acre base was not some personal dodge of accountability — it’s official US military policy. The military says maintaining a public stance that its nuclear weapons are nowhere — or, possibly anywhere — denies adversaries “militarily useful information” while also enhancing the “effectiveness of nuclear deterrence.”

Critics say the secrecy is meant to dampen public awareness, not to evade sophisticated foreign militaries:

“I would argue that this idea that you cannot confirm or deny that location at a base has absolutely nothing to do with secrecy. That is entirely just trying to chill a public debate.”

“I would argue that this idea that you cannot confirm or deny that location at a base has absolutely nothing to do with secrecy. That is entirely just trying to chill a public debate,” says Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

The “neither confirm nor deny” policy dates back to the late 1950s when the presence of US nuclear weapons in allied nations became a “political irritant” among otherwise allied nations, whose citizens often called on politicians to refuse to host such weapons during peacetime, Kristensen said.

US commitment to the no-comment policy led to the suspension of alliance commitments to New Zealand in the 1980s after the latter declared itself a nuclear-free zone, meaning ships that couldn’t confirm they didn’t hold nuclear weapons should not dock there. The US would only normalize military relations with New Zealand in 2016.

Related: What you need to know about modern nuclear war

“There’s a sort of silliness about the extent of secrecy,” Kristensen said. For example, he said the US government has repeatedly stated that surface ships no longer have the capability to hold nuclear weapons, but, if asked, an aircraft carrier captain is still obliged to give the military-wide official “no comment” line.

“As a citizen of this country, you’re sort of raised to appreciate certain values and to understand that our system works in such a way that information is available to people and there is some sense of consent in how you’re being governed. … Secrecy is basically the lifeblood of the crimes that this nation is committing.”

Plowshares 7 member Mark Colville, a 57-year-old anti-nuclear activist and father of six who, before he was arrested, ran a Catholic Worker home in Connecticut, said he felt “disgust” when the base’s captain refused to answer whether Kings Bay held nuclear weapons.

“As a citizen of this country, you’re sort of raised to appreciate certain values and to understand that our system works in such a way that information is available to people and there is some sense of consent in how you’re being governed,” he said in a phone call from the Georgia county jail where he has spent nearly a year since his arrest.

“Secrecy is basically the lifeblood of the crimes that this nation is committing,” he added.

‘Stealth’ submarines

Kings Bay and its West Coast counterpart, Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, in Washington state, both house nuclear weapons and the stealthiest mechanism to deliver them.

The US possesses a “nuclear triad” — which means the ability to launch nuclear weapons from land, air and sea — and the fleet of 14 submarines housed between the two bases are its most enduring way to potentially strike adversaries should the US territory and land bases come under attack.

The submarines, with about 140 crew members, periodically set off from the US’ eastern and western coasts for about three months at a time. They avoid docking abroad and evade foreign detection, giving the US a retaliatory capability across the globe should its territory ever come under attack.

“If the country is overwhelmed by a surprise attack from someone that knocks everything out, there is always a fleet of submarines out there that they cannot destroy … we call it … a secure retaliatory capability …”

“If the country is overwhelmed by a surprise attack from someone that knocks everything out, there is always a fleet of submarines out there that they cannot destroy … we call it sort of a secure retaliatory capability — that there is no country that has the capability to hunt down these submarines and prevent us from launching a retaliatory strike if necessary,” Kristensen said.

Of the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons, even fewer possess the ability offered by such submarines to launch a nuclear attack virtually anywhere in the world.

Scott Bassett, the public affairs officer for Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, was upfront in an email to The World about ballistic missile submarine presence at the base. He wrote that the 9,000 military personnel, civilians and contractors who come daily to the base for work keep its ballistic missile and guided missile submarines in “stellar” condition so that those “vital assets” can “execute the Department of Defense’s number one mission of strategic deterrence.”

Related: How Trump’s exit from a Cold War-era treaty could trigger a 3-way arms race

Bassett declined to comment on the blood-painting Catholic activists since their case is still under litigation in federal court. He did acknowledge, however, that diplomacy has led to gradual weapons reductions: Four of the 24 ballistic missile-carrying tubes on each of the six Ohio-class submarines at Kings Bay have been deactivated due to the 2011 New Strategic Arms Reduction, or New START, treaty with Russia.

The new Columbia-class submarines expected to replace the Ohio-class by 2028 will carry a maximum of 16 missiles. The types of missiles held on their submarines are also no secret, Basset said: The Navy films and broadcasts its capability in order to keep potential adversaries wary, thus accomplishing their deterrence mission.

Rising nuclear anxiety

The steps toward disarmament at Kings Bay still come amid a backdrop of rising nuclear anxiety and a spending spree on such weapons. After a call from global civil society, much of the world has rallied behind a nuclear arms ban treaty, which 70 countries have already signed.

Related: Can the Ban Treaty eliminate the threat of nuclear war? The clock is ticking down

Advocacy for the treaty won the Geneva-based International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN, the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize. Going in the other direction, though, the Trump administration has abandoned arms control treaties, including a landmark Cold War-era missiles agreement with Russia and the Iran nuclear deal.

Related: Iran may sail around US sanctions with ‘cloaked’ tankers

It has also sowed doubt over whether it will extend the New START treaty in 2021.

In the meantime, the US government continues to spend billions in public money on nuclear weapons. The administration’s plans to maintain and upgrade its nuclear arsenal is expected to cost taxpayers about $50 billion a year over the coming decade, according to the Congressional budget office.

At Kings Bay, operated through an annual payroll and procurement budget of $874 million, according to Bassett, that upgrade means those incoming Columbia-class submarines are estimated to cost $100 billion over their lifetime.

Even a top naval official promoting the submarines said the price “will make your eyes water.”

Maintaining nuclear arsenals make the possibility of weapon usage not a question of if, but when, say anti-nuclear campaigners, such as Nobel Peace Prize winner Beatrice Fihn from ICAN.

Still, on the ground in Kings Bay and the surrounding county, where nearly half of residents either work at the base or are related to someone who does, that alarmism is hard to come by.

Lisa James, a local who works in finance, says she, like most locals, is aware that the base holds nuclear weapons. Her husband was a sailor deployed on the submarines for years; when he retired from the military, they chose to continue living in the area, a pleasant county where it’s hard to find a restaurant open after 6 p.m.

Only once — after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — did she feel fearful that she and her hometown of choice could be a target for an enemy seeking to take out critical weapons infrastructure in the US.

“All of the sudden it occurred to me: We live at ground zero,” James said.

She appreciates that the activists who trespassed on the base did so in the name of promoting peace, but said that she believes in US nuclear deterrence as a “very responsible way” to prevent war.

On April 26, a federal magistrate denied the Plowshares 7’s motion under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The seven defendants, all Catholic, had testified with expert witnesses during their November 2018 hearings and waited 14 weeks for the final decision.

There is still no trial date set.

“We know there are some things working silently and secretly on our behalf. … I don’t think there’s anyone who’s waking up concerned about what’s happening on the base.”

“We know there are some things working silently and secretly on our behalf,” she said of the submarines’ mission.

As far as she and her neighbors go, she added: “I don’t think there’s anyone who’s waking up concerned about what’s happening on the base.”

Editor’s note: We’ve partnered with a video game company to let our readers put themselves in the shoes of someone who deals with nuclear weapons. Try the game for yourself at nucleardecisions.org.