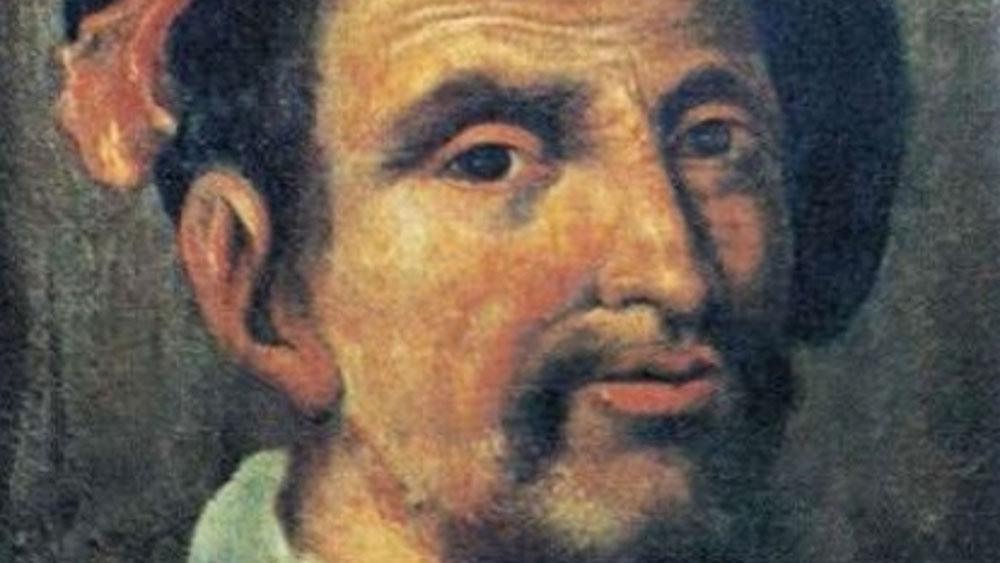

Christopher Columbus’ son, Hernando Colón.

Hernando Colón, the illegitimate son of Italian colonizer Christopher Columbus, had an obsession with books. Colón traveled the world to attempt an ambitious dream: to collect and store all of the world’s books in one library. Summaries of the volumes he gathered were distilled in the “Libro de los Epítomes,” or “The Book of Epitomes” — that repository had been lost to history for centuries.

But “Libro de los Epítomes” was rediscovered at the Arnamagnæan Institute in Denmark last week, sitting among a collection of books donated by Icelandic scholar Árni Magnússon to the University of Copenhagen upon his death in 1730.

Edward Wilson-Lee, a professor at Cambridge University whose recent book “The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books” details Colón’s life, spoke with The World about the significance of this Colón’s work and what this discovery means.

Edward Wilson-Lee: This is part of a wider, extraordinary story about Hernando Colón. He was the illegitimate son of Christopher Columbus and, because he was illegitimate, he felt like he needed to prove himself as his father’s worthy heir in spirit, if he wasn’t legally his father’s heir.

As a counterpart to his father’s project to circumnavigate the world, sail west and return from the east, Hernando decided to build a universal library, which would have every book in the world in it — with every book, in every language, on every subject.

This was right at the dawn of the era of print, so the number of books was rising exponentially. He realized that the idea of this library was a wonderful one, but of course, it might become unmanageable if he was just collecting the books and not finding a way to organize and distill them. So he paid an army of readers to read every book in the library and to distill it down to a short summary so that all of this knowledge could be put at the disposal of a single person.

It’s this book, the “Libro de los Epítomes,” that is described by his last librarian in a document at the end of Hernando’s life, but then disappears and isn’t really heard of for basically 500 years because it’s been sitting for at least 350 of those years in Scandinavia, where it was unrecognized. An academic from Canada thought it might have something to do with Hernando’s library. As I had been working on this biography of Hernando and I’m working on an account of the library with my colleague from Spain, José María Pérez Fernández, [I] was in the right position to be able to fly over to Copenhagen very excitedly and verify that this is indeed a key missing piece of Hernando’s great library project.

Marco Werman: So, you’ve laid out a lot of history there, but at the heart of what you’ve just said is a really wacky idea — a giant book of the world’s books. What can you tell us about Hernando Colón and his life? Because it’s wild for somebody to come up with this idea.

He had this obsessive–compulsive desire to list things. He not only compiled this most enormous library of his day — this universal library — he had the largest collection of printed images in the world. He had the largest collection of printed music in the world. He started a dictionary, which only got to the letter “B,” but it’s 1,432 pages by the time he gets to that point. So, it’s no mean effort. He started the geographical encyclopedia of Spain and he may well have begun the first botanical garden in the world. He had this extraordinary, compulsive need to compile things, to put [them] in order and to list them. Books were really his great love. Very few people, almost no one other than Hernando, really saw how print was going to change the world. Book collectors at the time collected largely manuscripts. They wanted the oldest manuscripts of Plato, Cicero and things like that.

Related: The Dead Sea Scrolls are a priceless link to the Bible’s past

That is a very Renaissance thing, to collect stuff like that.

Indeed. But Hernando recognized that print was different. How print was going to change the world was not by making this elite ancient material available, but by making cheap and very current material available. Early news sheets, weather forecasts and the earliest proto novels, Hernando collected this material, and this is really what’s so exciting and important about his library. It’s a very modern story: Anyone who’s lived through the last 20 years knows the extraordinary ability of information and the way it’s organized upon our lives and how it shapes our lives. I think you know Hernando’s story is very much like that. It’s about [how] the ways in which we organize information — especially during information revolutions — fundamentally reshapes the way we see the world.

What was Hernando’s relationship like with his dad, Christopher Columbus?

They had this extraordinary relationship built, in part, on the fact that Hernando went on Columbus’s fourth and last voyage to the New World and it was an utter disaster. At the end of it, the two of them spent a year living together on a shipwreck off northern Jamaica, and you really can never get to know someone quite as well as spending a year living on a shipwreck with him. He knew his father in this incredibly intimate way and he idolized his father. When he came to write the biography of his father — which was a defense of his father because in the decades after Columbus’ death his reputation was very much in the balance, not for the reasons it is nowadays, but for the reason that people didn’t think that this obscure Genoese person should really be given the credit for changing the world in the way he did — Columbus’ fame started to slip away and it’s really Hernando who writes his father’s story. He writes this story of a visionary who beat the odds and who turned against all the critics and saw his vision through. That’s the story of Columbus that the romantics idolized and became this great symbol of achievement for later history. The true story of Columbus is slightly buried in all that in part because of the love of his son.

You spoke of the obsessive need to make lists and compile things by Hernando, but was his undertaking also a deliberate contradiction of how his father saw the world, a place to conquer, and he kind of saw it more holistically?

No, I think it’s also true that Hernando’s desire to compile a universal library was as a tool of great power. He also wanted to put this library at the service of Spain’s universal empire. The idea was that a universal empire would require a central nervous system and that this library would be the central nervous system that, like with Google or Facebook nowadays, if you have all of the information in the world and ways of distilling it and sorting it and making it usable, that confers enormous power upon you. Hernando was not being entirely altruistic in the ways that he compiled this library, he viewed it very much as a counterpart to what his father was doing.

Related: Unsealed records of Pope Pius XII could shed light on Vatican’s turbulent postwar years

What happened to Colón’s library after he died?

As the story often goes, he left the library to a nephew who, unfortunately, was also a wastrel and who was notable largely for being imprisoned in North Africa for bigamy and who didn’t care about books. So, the books bounced around. They spent time in a monastery and then they ended up in the Seville Cathedral, where again, because people didn’t really recognize the worth of what Hernando had done, a lot of people saw these pamphlets that he had collected as just trash. It was locked away in an attic room where, for hundreds of years, its importance was unrecognized. During that time, theft and damage from weather and various other things reduced it to about a quarter of its original size, and there is still that quarter in Seville, but the rest of it we only know through these catalogs.

You authenticated this giant volume. Were you able to pick it up? What did it feel like?

It is a monster of a thing. It’s about a foot thick, it’s 2,000 pages long. They didn’t manage to summarize all the books in the library. The library at Hernando’s death was 15,000 to 20,000 volumes and they only summarized 3,500 of them. This manuscript is not complete, so there’s a little over 2,000 books summarized in this. But, very excitingly, many of these books will probably not survive anywhere else in the world in any other form, so this is a catalog of lost books in a really exciting way. It is a gorgeous thing. As a scholar of early modern books and a lover of old books, it is really one of the most exciting things I’ve ever come across.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.