In new book, Lebanese Satirist Karl reMarks skewers Middle East pundits

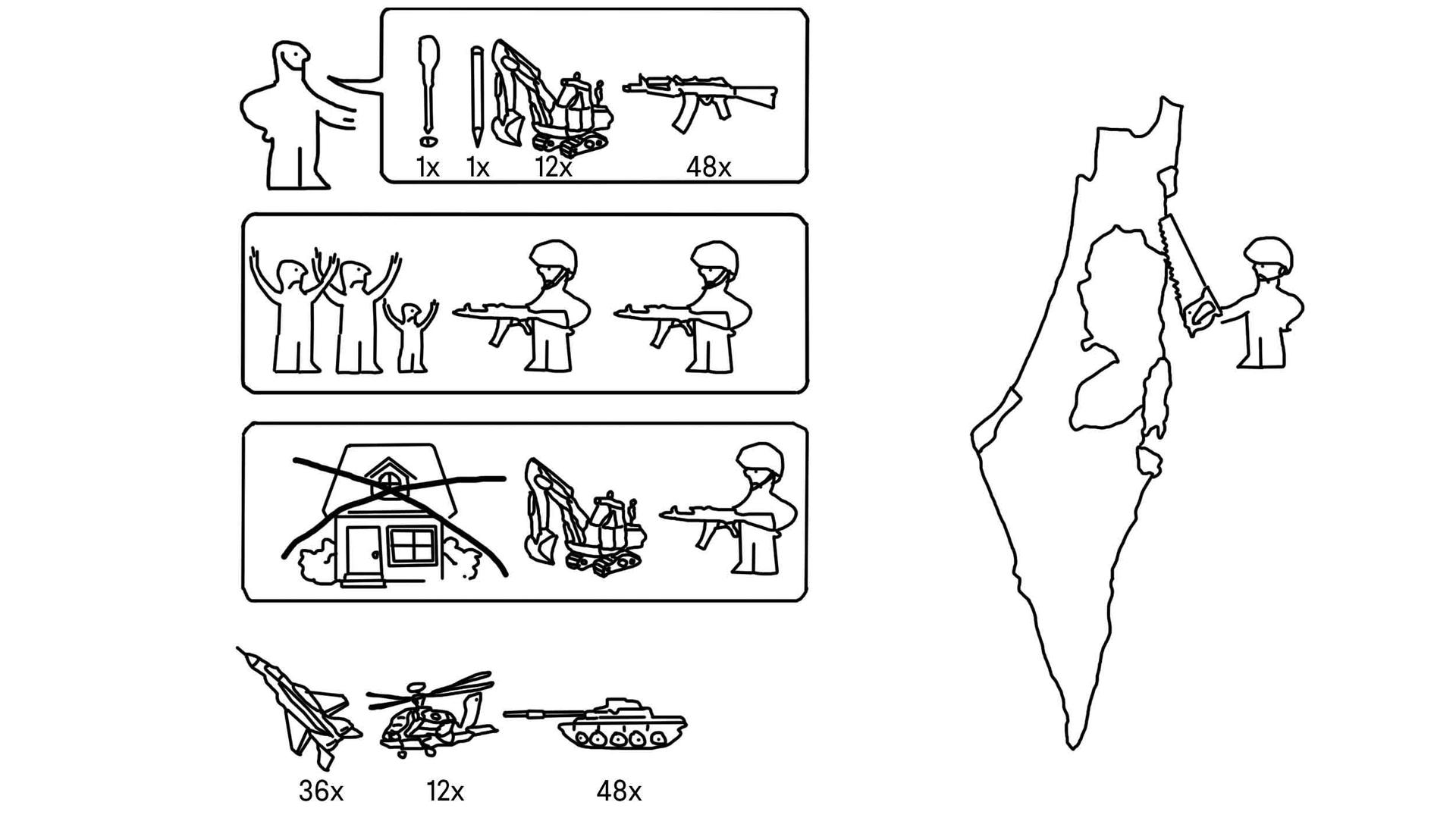

In this cartoon, Karl reMarks tells the story of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict stylized as IKEA how-to instructions.

By day, Karl Sharro is an architect in London. By night he is Karl reMarks, a Lebanese satirist whose distance from his homeland gives him a vantage point to employ humor to explain the Middle East to those not from the region. The World’s Carol Hills talked to Sharro about his new book, “And Then God Created the Middle East and said ‘Let There Be Breaking News.’”

Karl Sharro: The title came from an old tweet of mine, and actually the full title is “… And Then Said ‘Let there Be Breaking News Analysis.'” It was one of a series of observations that we were making about the international media’s obsession with reporting on the Middle East.

Carol Hills: Karl, I know you love to take on pundits, especially those who try to explain the Middle East.

One of my favorite things is when pundits say things like, “This aspect of the Middle East is complex, it’s thorny, and very difficult to understand. Here’s my 500-word article explaining it all.”

I really like your real or imagined comment by the Israeli foreign minister.

This was a while back. The Israeli foreign minister had gotten a bit of a beef with the Swedish government and then he said, “You know, the Swedish government needs to understand that relations in the Middle East are more complicated than IKEA furniture.” So, I produced this classic image of the IKEA, of how to put furniture together, but explaining the whole Israeli-Palestinian conflict. That’s one of my favorite drawings, and that has things like the different bits that you need: You need tanks, you need rifles. Then he goes on showing how you demolish houses and how to expel people. It’s kind of trying to explain that in the style of an IKEA guy.

Related: The Aleppo tragedy has left one Arab satirist with nothing to say

It’s interesting, you’re an architect and then you have this whole second life as a satirist. Why does the Middle East need satirizing?

Over the years, I started doing this in about 2011, I think, with the beginning of what was called, at the time, the Arab Spring. In the beginning, it was about just satirizing the dictators that we had, and the regimes. And then it morphed into this commentary on particularly international media, international punditry on the Middle East. I think those things are still operative. At some point, it also became the best response for me about the absurdity of the situation in countries like Libya or Syria where you have different sides, shifting alliances, and the whole thing kind of losing any sense of logic. You look at the complex web of alliances where — and when it comes to Syria and who’s on whose side and who’s shifting — satire became, I found, a more fulfilling way of responding to that.

You make a lot of observations about the West’s weird relationship with the Middle East, and you love to cheekily remind people of how much the Middle East has actually given the West, like when you visit museums.

You know, it’s like when I go to a European museum or a Western museum, it reminds me of when someone, a friend, borrows a book from you and then you visit them years later and you see the book proudly displayed on their bookshelves. So, for me as a Middle Easterner, when I visit the British Museum, I have a strong sense of that.

I also like it when you talk about traveling abroad how you don’t even bother to pack.

Yeah, I guess. You know, as a Middle Eastern person, travel is a big issue. Obviously, it’s been for a number of years for us, but I don’t particularly mind all of the scrutiny. I know if I’m going to show up with a Middle Eastern passport at the airport in a Western country or in America, they’re going to immediately refer me to the “VIP section,” as we call it. They’re going to search my clothes very thoroughly. I don’t even bother packing nicely because I know after they’re done, they’re going to fold the clothes very neatly.

I’m curious, do you get a lot of blowback from people who read your Twitter feed? Do you get a lot of reaction to what you write on social media, both from people from the Middle East and from people outside the Middle East?

I do get a lot of engagement. I don’t know about blowback. Predominantly, I would say, it’s not negative except when I’m particularly known for my awful puns. When I do a particularly cringe-worthy pun, then people are quick to put me back in my place.

But I haven’t shied away from controversial topics. I’ve done everything from dictators to satire about ISIS and all kind of complex issues. Occasionally, there’d be kind of critical responses but it generally tends to be from people who don’t actually get the joke. Just last week, I did this diagram where I compared — now that we’re hearing it’s the end of ISIS their caliphate is about to lose its very last territory — I did this comparative diagram where I showed how long ISIS lasted versus the other caliphates in Islamic history. ISIS had this tiny, tiny dot on the graph. I put on top of it an arrow saying, “This dot here.”

Now this was clearly mocking ISIS and mocking their pretense of being a caliphate. It was nothing, and it didn’t last at all. Obviously, it wasn’t in any conventional understanding a proper caliphate, but that’s what they claim. Now, clearly the joke was on ISIS and their pretense in the caliphate, but then I get a lot of responses saying, “How dare you call ISIS a caliphate? They’re not a caliphate! They’re not a proper caliphate!” And I’m like, “Yeah, but that is the joke.”

Try me on a pun. I can tolerate puns pretty well.

This is awful. I can write material but I can’t come up with responses on demand. Just the other day, my 9-year-old daughter said “What’s a pun, daddy?” and I said, “A pun is a play on words when you make, like, for example ….” And I couldn’t come up with a single pun. It was really awkward for two or three minutes, I’m trying to come up with one. I’m was like “God, please just give me one pun so I can explain it to my daughter.” I couldn’t come up with anything, not even an awful pun. My favorite one — and I then Googled it subsequently, and it turned out I didn’t come up with it. I thought I did, but apparently a lot of people had done it before. It’s, “The pun is mightier than the sword.”

Related: Three dictators walk into a bar… and a Lebanese satirist becomes famous

That’s great. What’s great is that you don’t hesitate to make fun of your own homeland and the MiddleEast in general. I like your take on Lebanese action figures.

Where every other country in the Middle East has one dictator, we have about 20 different dictators and they’ve all been in power for 30 or 40 years, sometimes. They’ve been there forever. Instead of doing action figures, I did inaction figures. There were marks and little collector’s boxes, and basically, they do nothing.

You also have a twist on the Russian nesting doll to illustrate Arab dictators.

Yeah, this came out of the frustration of the Arab uprising two or three years in, when you saw the people that left, the dictators that were removed, they were being replaced by other ones. I said, “An Arab dictator is like one of those Russian Matryoshka dolls but in reverse because every time you remove one, you get a bigger and nastier one.”

This was a more recent observation you made but it was about how Americans should name hurricanes.

Yeah, I guess this was about a year ago when you had the big hurricane but simultaneously, there was the whole story of the Muslim travel ban and then I said, “Well, I suggest they call hurricanes names like Mohammad or Fatima because then it would be impossible for them to enter the US.”

You’re Lebanese but you live in London and so you’re both within and without, in terms of the Middle East and what goes on there. Do you think that influences your approach to satire?

Oh absolutely, I think so. For the first 30 years of my life, I lived mostly in Lebanon, between Lebanon and Iraq, but mostly in Lebanon. I think I was way too close to the daily rhythm of life and politics and everything to make any funny observations about it at all or to make any meaningful observations about it at all. By removing myself out of this context, I have a bit of a distance. I have a certain coldness, a critical distance where I’m almost afforded the luxury of being able to comment in the situation humorously, particularly where perhaps, if I was still living there, I don’t think I would have been able to.

But at the same time, I think it puts me in a position where I’m not really experiencing the accumulation of daily changes and I’ve been away for almost 15 years now. It’s a bit of a warning that I’m not the most up-to-date observer on the Middle East and that’s why I often escape to very faraway history and the bad things that happened a thousand years ago. It’s much more comfortable than things that are happening today.

You think about this stuff a lot and I’m sure you read a lot of news, observations and sources about the Middle East. What are the persistent things Western journalists get wrong about the Middle East in terms of how they go about talking about it or are analyzing it. Are there certain tropes that they just can’t resist?

I think to be fair, because I don’t want to be kind of lumping everyone together, there’s a young, new generation of Western journalists who are embedded in the region, who speak the language, who are doing fantastic work. This is why a lot of my criticism tends to be about a certain generation who were, let’s say, less professional in the way they represented the Middle East.

The repetitive tropes that bugged me in particular is the obsessive desire to represent everything in the Middle East as if it’s always a product of 1,500 years of history or things that happened two millennia ago, of ancient hatreds and those kind of tropes, without contextualizing it within the actual politics of the day. It’s also, again, things like not understanding the nature of sectarianism. This is not in the DNA, it’s a product of very contemporary ways of doing politics and if they were looking at the West and they see a similar thing, they wouldn’t call it sectarianism. That’s again, one of the things that bugged me.

And the third one is a really weird one that started to happen again in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings and when things started to turn to civil wars. And I tweeted about this once, where some Western observers followed the news in the Middle East as if they’re following sports. They would have favorite sects and ethnicities. It was a bit of a joke, but there’s a truth to it that a lot of the journalists covering the region, they tend to have very clear affiliation with a particular group. They say, “We feel much closer to the Kurds.” They wouldn’t actually come out and say it like that, but it’s kind of carried in the tone of their observations and their reporting. So, they’re closer to the Kurds or closer to the Sunni Arabs. I find that quite unprofessional. At the same time, it’s damaging to the integrity of journalism and that’s one of the things that really irks me.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and length.