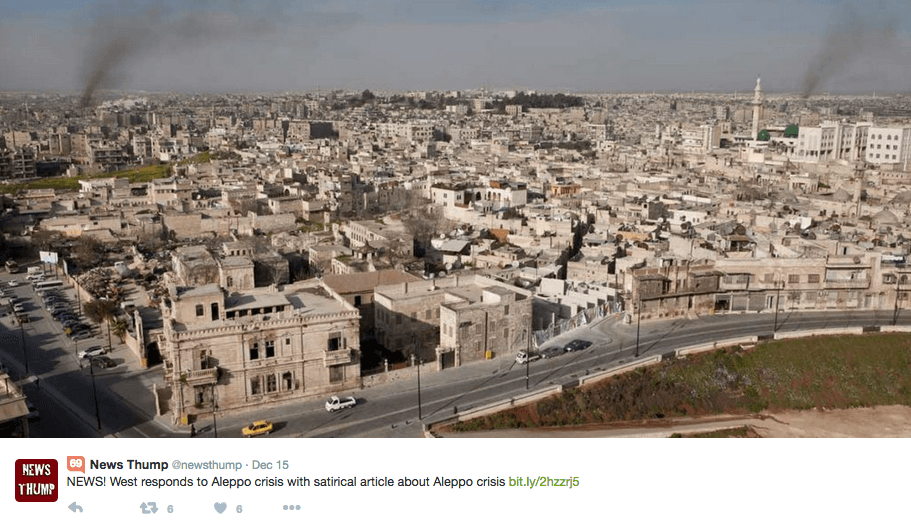

A spoof article by the British satirical news site, News Thump (think the Onion), is shown here, mocking the inaction of the international community toward the tragedy in Aleppo.

Satire is not always funny ha-ha. It's often funny as in, devastating, dark — a comment or image that makes you wince or even squirm because its message is so on point.

The tragedy in Aleppo is what many satirists are trying to grapple with at the moment. The default message in many political cartoons is a plaintive cry: "Take notice. This is happening right now. Help us. I dare you to look away."

But Aleppo is a topic that has vexed Karl Sharro, a popular Lebanese satirist who goes by the name Karl reMarks. "For the first time, I'm kind of starting to see that satire has almost exhausted itself in terms of what it's able to say," he says.

The war in Syria is about to enter its sixth year, and there's no resolution in sight.

"There's almost a sense of the futility about satire. I'm not talking about whether it's appropriate or not. I just think in terms of its usefulness at the moment," he says.

Sharro thinks the dark tale of Aleppo requires nuance and complexity that's not usually a strength of satire. "We satirists and cartoonists tend to be blunt. We're more successful at things that appeal to a deeper emotional level."

International attention to Syria comes in waves. Ceasefires are called and just as quickly lifted or broken. There's moral outrage on all fronts. "That tends to draw more media attention," says Sharro, "but then people start to demand easy answers, and I think a lot of satirists and cartoonists in those situations are kind of tending to want to provide those easy answers."

Aleppo is having its moment now, but the eastern part of the city has been under siege literally for years. The protracted and violent resolution to the battle there — a barrage by Syrian troops with help from Russian air power — has reached the world through videos of trapped residents making direct appeals for help.

Sharro says one popular, easy line many satirists offer these days is that the world has lost interest and doesn't care about Syria. "It's like one of those abstract slogans that we can all talk about without actually saying what it is that we want people to do. It comes with a lot of moral posturing," he says.

Sharro the satirist has decided that retreating from writing or drawing about Aleppo is better than having a knee-jerk response.

He fears that the "we care about you" approach to raising awareness about Syria is based not on a universal sense of solidarity but on a dynamic between the victimized and those with the voice to express their concerns. "It's quite an unequal situation and that's why it creates, I think, a lot of bitterness," he says.

Conflict involving Syria is also personal for Sharro. He grew up during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). When he was 10 years old and already a budding satirist, his hometown was besieged by the Syrian army for three months. "We were constantly pounded and shelled. I remember us making jokes about the situation all the time and kind of coping." That experience makes him even more reluctant to apply satire to Aleppo. "It's kind of too close to home. I'm not there. It's a city I'm familiar with. It's almost like you can't give yourself the right to joke about the situation if you're not in it."

One satirist who is there is Jiim Siin, a Syrian mostly living in exile who produces a satirical audio blog. The Arabic title translates to "Chronicles of the Pressure Cooker." Sharro says Siin's monologues, audio plays and absurdist skits try to make sense of the Syrian civil war.

"It's quite bleak, quite dark. It's not afraid to take sides politically and morally. I think there's a sense of when you're playing to an audience of fellow Syrians, even if you're doing satire at a very bleak moment in the history of your country, there's more immediacy to it than playing to an abstract international audience."

For Sharro, Aleppo and the war in Syria are about something larger: the sense of paralysis, stagnation, autocracy and the near-civil war in some countries affected by the Arab Spring uprisings. "Maybe it's a critical moment in terms of reflecting about the role of satire. I'm not saying abandon it, but is there a more clever way of doing it that's more specific instead of making them flattened out victims in an ongoing tragedy."