In this California classroom, students teach each other their home languages — and learn acceptance

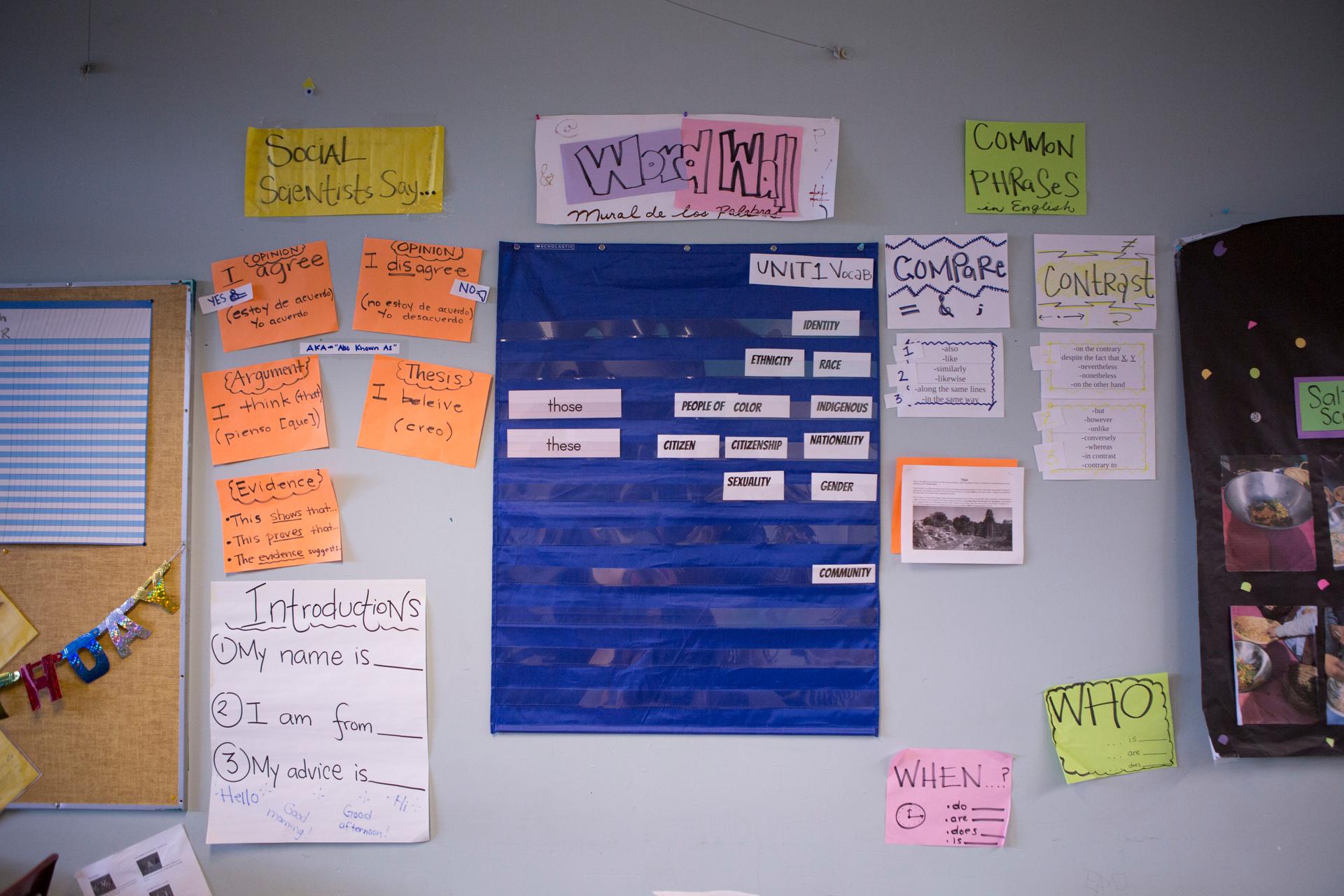

Acacia WoodsChan leads an introductory exercise in ethnic studies class for two new students at Castlemont High School in Oakland, California, on Feb. 4, 2019. Last year, WoodsChan had her students create a video dictionary to help them learn words in Mam, an Indigenous language from Guatemala, Arabic and Spanish.

In Acacia WoodsChan’s ethnic studies class at Castlemont High School in Oakland, California, students chat with each other in Spanish, Arabic and Mam, a Mayan language from Guatemala. The students have only been in the US for a few weeks or months. Some are from Yemen, and many are from countries in Central America — Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras.

Last year, WoodsChan became concerned when she started hearing the Spanish-speaking students laugh when their classmates spoke Mam or Arabic or make fun of how those languages sounded.

“You could literally look at the faces of the students who spoke those languages — Mam or Arabic — and just see the level of disappointment,” she said.

WoodsChan came up with an idea. She asked her students to take turns teaching a little bit of their home language each day. Students taught their peers how to count from one to 10, how to introduce themselves and how to say basic phrases or words like, “Cool.” Then, they recorded themselves saying those phrases in short video clips.

Listen to them each saying the word “cool”:

And explaining how to introduce themselves:

WoodsChan says it made a huge difference.

“You could see a huge shift in the way that not only the Mam-speaking students regarded the importance of learning Mam and having it visible, but also in the way that the other students received it,” WoodsChan said.

WoodsChan’s classroom is just one of many across the country with an increasing number of immigrant students. In the last five years, Oakland Unified School District experienced a spike in the number of immigrant students from Central America. More than 200,000 children and youth under 18 were detained after crossing the border alone since 2014.

When a minor without a guardian turns themselves in at the border or is stopped by immigration authorities, they are turned over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. They are later released to live with relatives or friends, while they wait for immigration hearings to see if they can stay in this country. These students face formidable obstacles to get through high school. But they also bring powerful assets with them, one of which is their fluency in their home languages.

Research has shown that immigrants who retain their home language while learning English are likelier to graduate from high school, go on to college and enter higher-paying careers than those who learn English but lose their home language.

WoodsChan saw the difference in her students. She said they grew more confident after seeing their own languages on the whiteboard and hearing it in the video clips. They started making friends with each other — across cultural lines. Other students who were not in that class would come in and see something written in Mam on the board and exclaim, “Hey, that’s Mam! I speak Mam!”

Researchers at the Graduate Center of City University of New York say when students see their home languages displayed in the classroom or around the school, they feel more comfortable at school, and it helps students feel like experts if they are asked to share their knowledge of their home language with their peers.

Expertise in other languages can help WoodsChan’s students beyond the classroom, too. Indigenous languages like Mam are becoming more and more common in the United States. Several thousand Mam speakers are estimated to now live in Oakland, adding to a larger Mayan community in the Bay Area. Some Oakland graduates have gone on to become Mam-English interpreters to help fill a lack of Indigenous-language interpreters in all kinds of settings, from school to hospitals to courts.

Fifteen-year-old Wilfido, from Guatemala, says WoodsChan’s video project made him happy because “everyone wanted to learn Mam.” He was also happy to learn some Arabic, though he only remembers how to say hala hala, which is a greeting like “hi.”

He says now he’s inspired to learn more languages, and he wants to be an interpreter.

The project also helped students who didn’t speak Mam or Arabic understand their peers better. Orlando, a 17-year-old student from El Salvador, said he never knew Arabic or Mam even existed before he came to the US and heard his classmates talk. Now, he thinks it would be good for all students in his school to learn a little of their peers’ home languages.

“When students first get here,” he said in Spanish, “they think, ‘No one talks like me. I’m the only one,’ and they feel alone. This way, they won’t feel so bad.”

The students’ last names are not being disclosed because they are minors, and their immigration cases are still pending.

For WoodsChan, cultivating pride in her students for their own and others’ identities is personal — she’s African American and Chinese American. Her mother, who was born in the US, but spoke Cantonese at home as a child, told her that when she was in kindergarten and still learning English, she had a stomach ache, but she didn’t know how to say that word.

“So, she raised her hand and said, ‘Teacher, I have a stomach!’ and she’s like, doubled over in pain, her face is wrinkled and wrenched and just looking wretched,” said WoodsChan. “And the teacher was like, ‘Yes, of course you have a stomach.’”

That interaction was scarring for her mom, and WoodsChan keeps it close to her heart. She wants to be the opposite kind of teacher as the one who couldn’t or wouldn’t understand her mother.

“When I see my students, I think of my grandma, and I think of my mom,” WoodsChan said. “They’re fighting when they’re here every day. They’re fighting for their education.”

WoodsChan hopes her school will use her class videos as part of an orientation at the beginning of the year, to help build a sense of respect and mutual understanding among all students, both newcomers and those born in the US.

“I think a lot of the pitfall that we see here on our campus and in our society, especially at this time, is when you don’t have an in, when you don’t have a connection, you go to the default messaging, which unfortunately, is very negative, particularly right now towards immigrants and towards the ‘other,’” she said.

Editor’s note: To hear the Spanish-language version, go to Radio Bilingüe.

This story was produced with the support of the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship, and in collaboration with EdSource.