Getting legal status opened the path to college for this Arizona immigrant family

Jorge Lopez, left, and his mother Ana Chavarin (right) chat during a study break at Pima Community College last December. After the family got legal status, Chavarin enrolled in college and Lopez followed.

As Ana Chavarin cleaned strangers’ homes, scrubbed dishes in restaurants and vacuumed offices at night as an undocumented immigrant in Tucson, she craved the chance to get an education. Her mother made her drop out of school when she was just 13 so she could work at a factory in their border town of Agua Prieta in Mexico.

“I always had that idea in the back of my head [that] one day I am going to go back to school,” said Chavarin, now a 37-year-old mother of four. But once she and her family moved to the United States for better opportunities, her quest for education would prove more daunting than she ever could have imagined.

Undocumented immigrants don’t qualify for any federal financial aid for school. In many states, including Arizona, they don’t qualify for in-state tuition, either. And an Arizona law approved by voters in 2006 restricts certain adult education and child care programs to only lawful immigrants.

Related: Brain Gain: More stories about immigrants who are striving — and finding ways around roadblocks in the US education system

Without financial aid or in-state tuition, undocumented students’ education goals are often derailed, according to Roberto Gonzales, a professor at Harvard Graduate School of Education. And without work permits, they cannot count on the high cost of college translating to a job after graduation.

“For many immigrants hoping to attain post-secondary education, their undocumented status makes that pursuit prohibitive,” Gonzales said.

For Chavarin and her children, a college degree only came within reach when she eventually got legal immigration status. Even so, as a foreign-born working parent, and the first in her family to attend college, the odds were stacked against her. Only one-fifth of part-time community college students manage to get a two-year associate’s degree within six years, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Despite the challenges, Chavarin now has associate’s degree and plans to pursue a doctorate’s degree. She said she has her children in mind.

“I just want to inspire them,” Chavarin said.

Finding her calling

Chavarin’s education journey began about ten years ago when she found her life’s calling. It was born out of a nightmarish episode that changed her life. One night, she was coming home from her cleaning job when a stranger attacked and sexually assaulted her.

Chavarin spiraled into post-traumatic stress disorder. Therapy saved her. She had picked up English by then, but in group counseling, she met other immigrant assault survivors who only spoke Spanish. Chavarin saw a need for more counselors who could offer them therapy in their language. She knew then she wanted to become a bilingual therapist to help others overcome trauma.

“I was like, ‘This is the moment,’” Chavarin remembered. She got her GED. And Chavarin also learned about a special visa called a U visa for immigrant crime victims who cooperate with police. She helped law enforcement prosecute her attacker, and her visa application was approved, giving her legal status in the United States.

For the first time in her life in this country, Chavarin had a work permit, Social Security number, and no longer had to fear deportation. Most importantly for her education, the visa meant she would be charged in-state tuition at Pima Community College — instead of three times that rate she would’ve owed as a non-resident. Chavarin’s husband and her three eldest kids, who were born in Mexico, were also able to get legal status thanks to her U visa. She said it was “life-changing” for the family — though she grapples with the fact that this benefit was born out of something horrific.

“I know that many immigrants dream to have their documents,” Chavarin said. “The way I got them is not the best way. That is not something that anybody wish [for]. But at least after surviving that traumatic experience something good came out of it.”

Chavarin enrolled part-time in Pima Community College to study psychology in 2013.

“To me, it was an addiction,” Chavarin remembered when she first started taking classes. “I wanted to be there in class every day. I wanted to learn more.”

Two generations in college together

A few semesters after Chavarin started her college courses, her eldest son, Jorge Lopez, who is now 21, followed her footsteps and enrolled at Pima Community College, too. Last month, mother and son chatted at a table outside the cafeteria between final exams.

“I got an 88 on my nutrition exam,” Lopez told his mother.

“That’s good,” Chavarin said. “Are you satisfied?”

“No,” Lopez replied. “But it’s alright.”

Lopez, who is studying to become a nurse, told his mom his next exam was on lactation and pregnancy.

Chavarin smiled and said, “Oh, I can help you with that one!”

Lopez wants to eventually get his bachelor’s degree and become a registered nurse. He said his new immigration status and his mom’s example made this path possible.

“Her being so motivated to first get her GED and then be the first one to go to college definitely gave me that motivation to [be] like, I got to do it as well,” Lopez said.

When Lopez arrived on campus, Chavarin offered him tips on everything from the best professors to how to solve certain statistics problems. Some semesters, they shared textbooks and carpooled.

“She definitely encourages me to do my homework,” Lopez said. “You know, I can’t really like lag around and just waste my time because she’ll be walking around and she’ll see me, and she’ll tell me to get on top of it.”

Education experts say when immigrant adults get the chance to go back to school, it benefits the next generation.

“It lifts the trajectory of their children and family,” said Margie McHugh, who studies immigrant education for the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, DC. “The example of a parent who is taking studying seriously, who is carving out time in the home in front of their children to study themselves – that example is priceless for young people.”

Even with in-state tuition during those early days at the community college, Chavarin and Lopez struggled to pay for school, since the U visa still did not allow access to federal financial aid. Their part-time tuition has cost around $750 to $990 each semester, depending on the number of credits.

One semester, Lopez could not afford tuition and worked at a gas station full-time to save up. Chavarin relied on small scholarships and donations to get by.

Today, Chavarin and Jorge are legal permanent residents and can finally get federal financial aid for school. Even so, Lopez still works 30 hours a week at the gas station. Chavarin works more than 65 hours as a community organizer with Pima County Interfaith Council and cleans office buildings at night.

On top of it all, Chavarin has three younger children ages 13, 15 and 17 to care for at home. After the attack, her marriage ended, and she considers herself a single mom.

A new family tradition

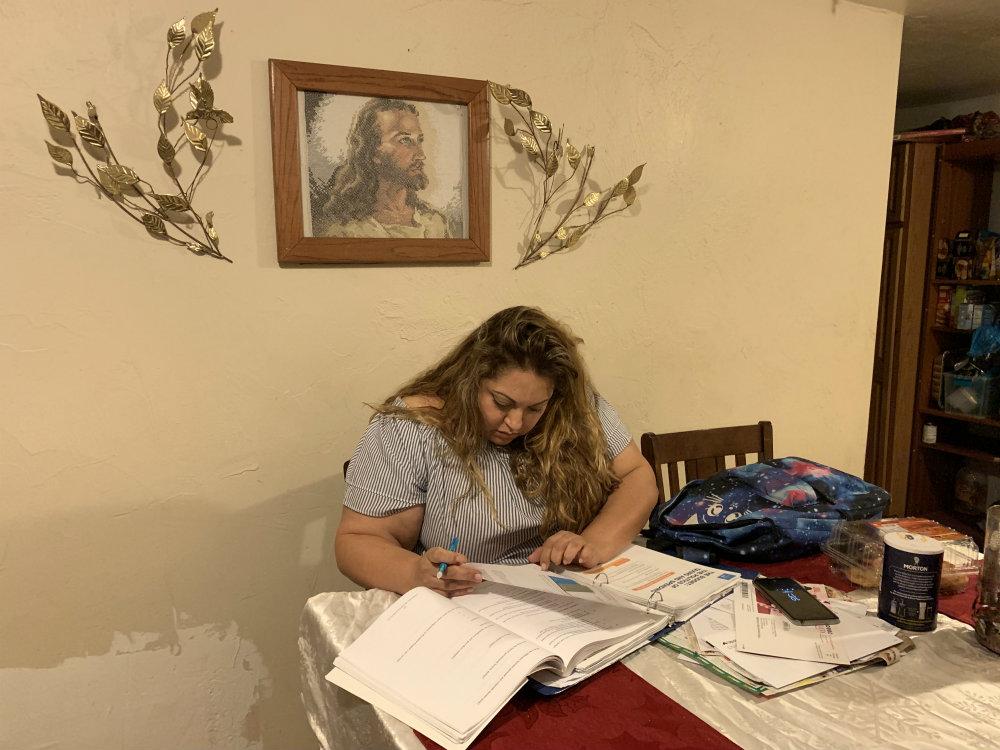

One evening during exam season last month, Chavarin sat at the family dining room table with her textbooks spread out in front of her.

Lopez came home from his gas station job, still wearing his red polo shirt uniform. It was almost 11 p.m. This slice of the evening is the only time Chavarin and Lopez have to get their homework done after days packed with classes, work and family duties. Chavarin confessed she was having trouble stringing sentences together after a long day.

“I tell you, my brain is tired,” Chavarin said. “I forget Spanish and I forget English.”

Despite how hard it is to juggle work, family and school, Chavarin is determined to keep going. In December, she earned her associate’s degree in psychology after less than six years.

“What she has done is a major feat,” said Marcella Bombardieri, a senior policy analyst at the Center for American Progress who studies the low graduation rate of part-time college students. “She’s already beaten the odds.”

According to Bombardieri, the typical college student today encounters many of the same obstacles Chavarin faces, such as being a first-generation college student, low-income and supporting a family.

“It’s obvious why all these factors would make it hard to succeed in college, but these are the realities of today’s students,” Bombardieri said. “So the higher education system needs to figure out how to adapt to better support students like Ana.”

This semester she is beginning classes at the University of Arizona to get her bachelor’s degree. Her ultimate goal is a doctorate in clinical psychology — even though that could easily take another decade or more.

“I try not to think about how many years because it is discouraging,” Chavarin said.

Instead, she thinks about the day she’ll have a diploma on the wall for her kids to see. Her mother may have pushed her to quit school all those years ago, but Chavarin wants her children to keep going.

It seems to be working. Her younger kids are already talking about studying law, graphic design and psychology. Chavarin said by the time she finally gets her PhD, her children might be parents themselves.

“And probably they can tell their kids, ‘Look, Nana did it. You can do it, too.’”