Ignored and deported, Cree ‘refugees’ echo the crises of today

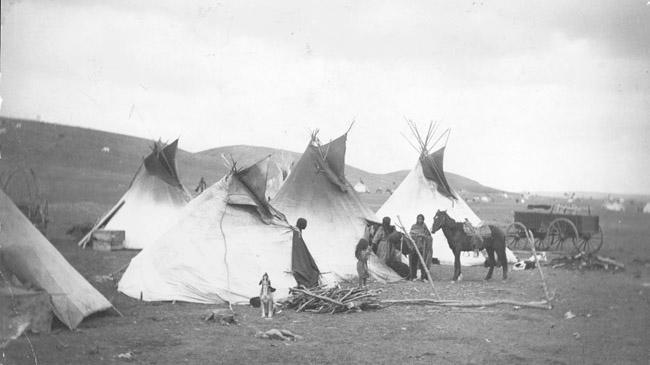

Crees had been present in Montana for decades and viewed their homeland as the northern Plains on both sides of the border. But because they were considered foreign, Little Bear’s Crees were not granted reservation settlement as American Indians for decades. Pictured: Chippewa Cree in Havre, Montana, March 8, 1909.

Indigenous Crees were native to Montana and the northern Plains long before the US-Canada border divided the region. But bisected by the line, Crees became asylum-seekers on their own lands 150 years ago. Though some were granted political refugee status, Crees were still denied basic rights. Instead, many were killed, ignored and deported on both sides of the border.

“This history is still in the minds of Chippewa Cree tribal members,” said Edward Stamper, a tribal member, and retired foundations and research director at Stone Child College. The Chippewa Cree story is little-known outside the tribe, but it echoes the uncertainty in the immigration crises the US faces today.

Just in recent days, the US House of Representatives proposed granting Venezuelan refugees Temporary Protected Status amid a growing humanitarian and political crisis in the South American country. TPS would protect Venezuelans already in the United States from deportation temporarily, but it is no guarantee of long-term residency. In December, the Trump administration revoked protected status of Southeast Asians who have lived in the United States for decades. For growing numbers of asylum-seekers petitioning the US, the idea of receiving — then losing — protected status is alarming. But deporting vulnerable populations has a sordid place in US foreign policy history — and its impact is lasting.

Native but ‘foreign’

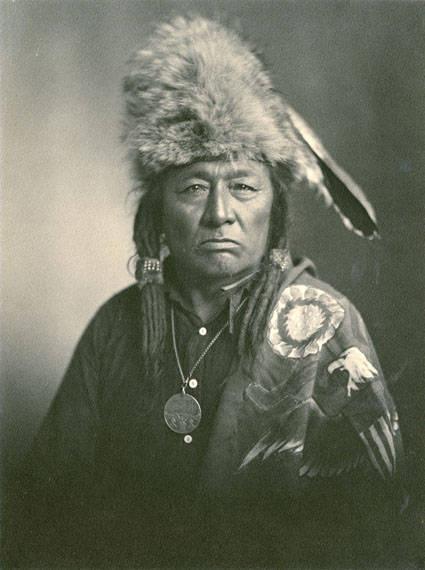

In the fall of 1885, Cree Chief Little Bear approached US Col. C. S. Otis in his office at Fort Assiniboine in Montana Territory and offered his hand. The officer refused. “Your hands are still bloody. I can’t shake with you,” Otis said.

Little Bear and his small band of 100-200 Indigenous Crees had just fought against the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the failed and bloody Northwest Rebellion — a First Nations and Métis uprising against Canadian rule and policies that led to disease and starvation across the northern Plains. The Cree band fled Canada and was seeking asylum in the US, looking for protection from Mounties who were trying to prevent them from crossing the border.

Little Bear’s band of Cree families traveled between Ft. Assiniboine and nearby Indian reservations looking for help. Otis and other government officials wanted to force them back to Canada. But without extradition requests, US federal authorities granted amnesty instead. Crees could stay in the country as political refugees.

Still, the cold reception Little Bear received at Fort Assiniboine was a precursor to future struggles. Labeled “foreign” Indians in the US, Crees were denied basic necessities, work — and eventually, even the right to stay in the country.

How could they be refugees when they were indigenous to the land? Borders transformed Native landscapes — regardless of whether or not they recognized those borders as valid. Little Bear’s Crees, and other groups, both flouted the border and co-opted its power. They crossed at will, showing that they did not recognize the power of the border to divide their lands. But they also used the border to escape — knowing that it meant something to US and Canadian officials, and they couldn’t be followed across the line.

Crees had been present in Montana for decades and viewed their homeland as the northern Plains on both sides of the border. But because they were considered foreign, Little Bear’s Crees were not granted reservation settlement as American Indians.

When Little Bear’s Crees arrived in Montana, the government was actively trying to decrease Native land holdings and open them to white settlement. “We have in Montana all the Indians we need … with a few thousand to spare,” wrote The River Press in 1887.

Montana, eager to progress from a territory to a state, needed to increase white settlement to strengthen their statehood petition. Landless Indians not only threatened to deter settlement, but their unregulated presence could dissuade Congress from granting statehood. Unsurprisingly, Montana public sentiment was vocally prejudiced against the Crees wandering the state.

Little Bear appealed to Montana Gov. John E. Rickards on behalf of his Cree band in 1893. Rickards, in turn, advised federal authorities that Crees should either be provided citizenship, granted a reservation or be deported back to Canada. Aware of popular opinion, Rickards favored the latter.

Little Bear then wrote directly to President Grover Cleveland, “The Great Spirit only knows how we shall subsist in case we do not receive assistance from the United States Government.” His appeal seems to have gone unanswered.

Instead, just 11 years after Little Bear’s Crees were granted asylum, federal authorities opened communication with Canada and arranged for Crees to be physically removed from the US.

Deported and deserted

In 1896, John J. Pershing and his 10th Cavalry Regiment captured and deported Crees and any other “Canadian” Indians they found. Many American-born Indians and Métis were deported in the process.

The deportation was brutal. Forced to walk north or loaded into cattle cars, families were separated, meager possessions were lost and some Crees died. Despite Canada’s cooperation in receiving them at the border — and much to the chagrin of US officials — many escaped and returned to the US. Some “circled around the troops and reached Fort Assiniboine ahead of the soldiers who had taken them across the border,” complained The Anaconda Standard.

Canada had promised amnesty for participants of the Northwest Rebellion, but unbeknownst to them, Little Bear and others were excluded from that protection. They were arrested at the border. Somehow, Canadian courts failed to convict all of them, and Little Bear returned to the US in 1897.

With funds spent, the US immediately gave up on more deportations and ignored the returning Crees, who were caught in legal limbo. For the next 20 years, federal government officials hoped that if ignored, the Crees would return to Canada on their own.

Instead, families struggled. They separated to find temporary wage labor, shelter or charity. Bands cycled between cities, frequenting slaughterhouse yards to collect discarded offal, and scavenging wherever possible. Each winter brought exposure, disease and starvation.

“My children are not lazy; they are eager and ready to go to work … The white man lets foreigners come here and gives them work, but they will not do that for the Indians and we will starve … there is nothing left but starvation.”

“They literally had to live off of rummaging through city dumps, eating their dead horses and dogs in order to survive the starvation that threatened them,” said Stamper.

When they asked for help, they were often denied. In a blurb headlined, “Indians cry for bread,” The Anaconda Standard reported: “Several Cree Indians called on the county of commissioners yesterday with a story of starvation threatening their band … The commissioners tried to explain to the Indians that they had no claims on this community and had no business to be here, and therefore the county could not assist them.”

When cities, counties or Indian agents did provide, it was often with protest. After giving critical food aid to Cree children in the winter of 1912-1913, Hill County complained that “the burden does not properly belong to its taxpayers and [it is] getting tired of being saddled with it.”

But Little Bear was determined to secure a permanent Montana home for Crees, despite settler opposition.

In a 1913 newspaper interview, Little Bear said: “My children are not lazy; they are eager and ready to go to work … we cannot secure employment because of the antipathy of the white man for us. When winter comes we will be without food and wood and clothing and blankets. … The white man lets foreigners come here and gives them work, but they will not do that for the Indians and we will starve … there is nothing left but starvation.”

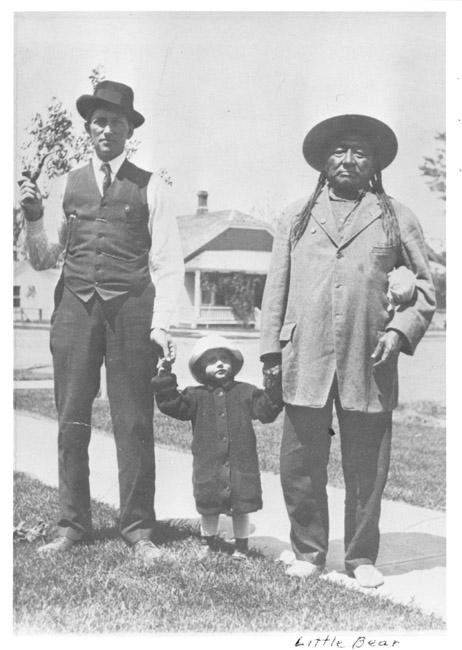

He began to build a coalition of businessmen and politicians who could use their personal influence to fight local prejudice and spur federal action. Many of these allies had already been working to settle a band of landless Chippewas led by Chief Rocky Boy in Montana, and eventually included Little Bear’s Crees and others in those efforts. In 1916, they successfully secured joint settlement as the Chippewa Cree Tribe of the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation in 1916. They were finally granted territory, ironically close to where Col. Otis had refused Little Bear’s hand and Pershing’s deportation campaigns had begun decades earlier.

Little Bear’s Crees struggled for three decades as Indigenous refugees in the United States, despite their direct ties to the land and legal protection within US borders. Federal inconsistency, indifference and inaction made resettling in the US even more difficult.

Today, the Chippewa Cree Tribe persists in Montana, providing for a growing population on the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation and elsewhere. Now officially recognized as “American” Indians for barely a century, experiences of crossing borders are still part of the tribe’s collective memory.

Some families regularly talk about their histories and appreciate what their ancestors went through, says Stamper. Moreover, Stamper says many maintain ties across the border to visit relatives, join in family reunions and attend Sun Dances and powwows in Canada. For some, however, it is a past too painful to revisit. Stamper and others at the tribe’s Stone Child College have worked to help the rising generation “retain this history.” “The History of the Chippewa Cree of Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation: 2008,” co-authored by Stamper, is one of the few books that touches on this story.

Descendents of Little Bear, Rocky Boy and others view the northern Plains on both sides of the border as their rightful home.

“For the Chippewa Cree,” Stamper said, “there should not even be a border.”

Editor’s note: Brenden Rensink is the author of “Native but Foreign: Indigenous Immigrants and Refugees in the North American Borderlands,” a book comparing the experiences of Indigenous migrants and refugees from Canada and Mexico in the United States.