Cuccinelli’s ‘bootstraps’ line reflects historical amnesia of ‘public charge’

Public Health Service physicians checking immigrants arriving to the United States for signs of illness. The immigration law of 1891 made it mandatory that all immigrants coming into the United States undergo health inspection by Public Health Service physicians. The largest inspection center was on Ellis Island in New York Harbor. In this 1910 photo, physicians are looking at the eyes for signs of trachoma.

On Monday, US Citizenship and Immigration Services announced changes to the application of the “likely to become a public charge,” or LPC, clause that would make it more difficult for legal immigrants who seek public assistance to qualify for permanent residence and citizenship.

Trying to justify the new rule, acting USCIS director Ken Cuccinelli said that the United States should only admit immigrants like his Irish and Italian ancestors who “came up from their bootstraps.”

This is a common refrain among Americans who support stringent immigration laws. Many argue that their ancestors came in legally and succeeded in the United States without any help or being a burden to society. The historical record shows otherwise.

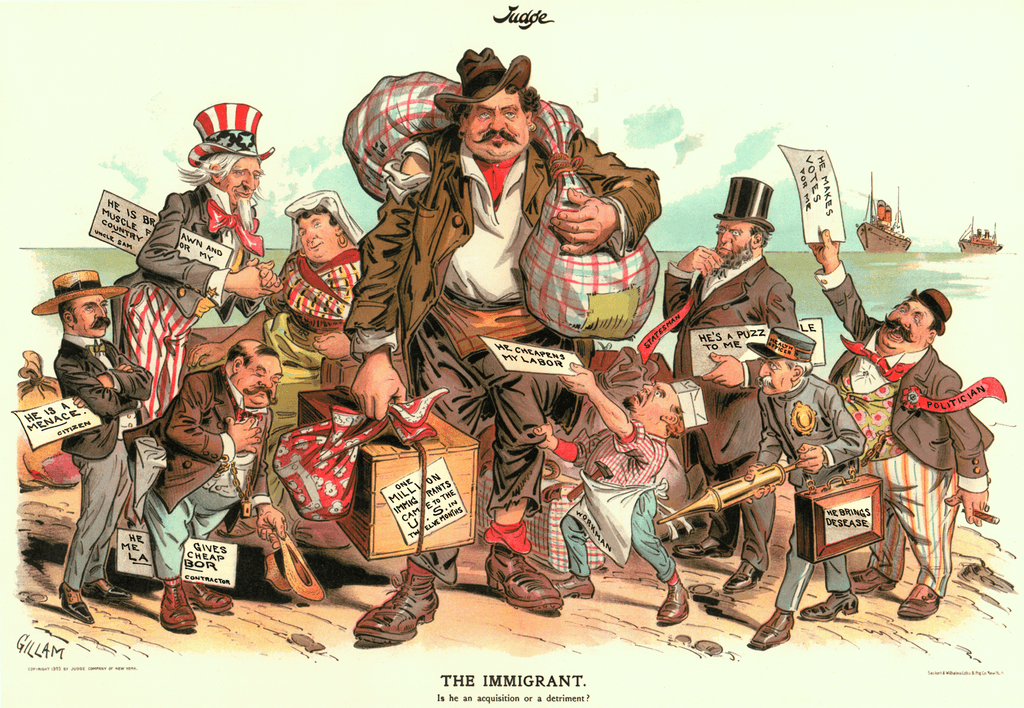

In fact, many Americans at the turn of the 19th century felt the same way about Cuccinelli’s ancestors as he appears to feel about today’s immigrants with limited means. The LPC clause originally targeted “undesirable” European immigrants, particularly those from eastern and southern Europe. It later emerged as a powerful tool to separate families of European immigrants trying to reunite in the United States.

Related: Public charge rule has history of ‘racial exclusion,’ says immigration historian

Between 1871 and the outbreak of World War I, 12.9 million immigrants arrived in the United States from Asia and Europe in search of economic opportunities, social mobility or safety. They joined millions of migrants around the globe who, at the end of the 19th century, left their countries to escape stagnant economies, political unrest or persecution to take advantage of the demand for unskilled labor in rapidly industrializing nations.

By 1920, the three largest groups of immigrants in the United States were Italians (4 million), eastern European Jews (2 million, mostly from the Russian Empire) and Poles (1 million). Many Americans of northern and western European ancestry regarded these new immigrants as nonwhite, biologically and culturally inferior, and unassimilable.

Related: Another time in history that the US created travel bans — against Italians

As an observer put it in 1888, “I have stood near Castle Garden and seen races of far greater peril to us than the Irish. I have seen the Hungarians, and the Italians and the Poles. I have seen poor wretches trooping out, wretches physically, wretches mentally, wretches morally, and stood almost trembling for my country, and said, what shall we do if this thing keeps on?”

Immigration laws emerged as the ideal tool of social engineering and nation-building. As a leader of the Immigration Restriction League said in 1919, “immigration restriction is a species of segregation on a large scale, by which inferior stocks can be prevented from both diluting and supplanting good stocks.”

In 1882, Congress took action and barred most Chinese immigrants and the poor along with “convicts, lunatics and idiots.” Before then, individual states, drawing from colonial British poor laws, had long sought to exclude the poor from arriving in the United States. In 1882, the LPC clause became the law of the land.

Related: The US has come a long way since its first, highly restrictive naturalization law

As more eastern and southern Europeans kept coming, Congress passed additional laws in 1885 and 1891 targeting immigrants with disabilities or contagious diseases, political radicals and criminals in a continuing effort to control the “quality” of the immigrants coming into the country. But political leaders of northern and western European descent remained frustrated that these acts failed to stem the arrival of an additional 8.9 million European immigrants by 1900.

Immigration from Europe didn’t slow until Congress passed the 1924 Immigration Act, which imposed a near ban on immigration from Asia and introduced national origins quotas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere. But the LPC clause remained central to the US government’s efforts to reject or deport immigrants.

Related: Long before anxiety about Muslims, Americans feared the ‘yellow peril’ of Chinese immigration

In the 1920s, the clause became a tool to make family reunion more difficult. In one of many archival examples, Rabbi Jacob S. Duner arrived in the United States in 1923 from Poland and sent for his family to join him in 1924. When the family arrived, immigration authorities declared the youngest of his five children, 4-year-old Channa, feebleminded and ordered her deported. Duner arranged for an adult to accompany the child back to Europe. Immigration authorities admitted the rest of the family as non-quota immigrants, but a Board of Special Inquiry excluded the entire family as likely to become public charges when it found that a son, Michel, had a heart problem. The board excluded the wife as the accompanying adult responsible for taking him back to Europe and the remaining children because they would become public charges without two parents taking care of them. After much pressure from Jewish advocates, the Court of Appeals confirmed Michel’s deportation but admitted the rest of the family.

The LPC clause took on new power with the onset of the Great Depression. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover, following a suggestion from the State Department, issued an executive order mandating stricter application of the LPC clause for all visa applicants. After 1930, the State Department and consular authorities stretched the meaning of the LPC clause to require immigrants to possess substantial assets or provide proof that they had a sponsor in the United States who could provide for them.

Related: Trump administration’s ‘public charge’ provision has roots in colonial US

The executive order particularly penalized women trying to send for their families. In 1931, Maria Mazzone, a naturalized immigrant from Campania, Italy, began the paperwork to reunite with her husband and their child, confident that her US citizenship would hasten the process. Several prominent Italian Americans and Pennsylvania Rep. Clyde Kelly, a Republican, intervened on her behalf, but the US consul in Naples denied Mazzone the visas because she had failed to prove that the entire family would not become a public charge once they reunited in the United States.

Authorities also used the LPC clause to penalize Mexican immigrants in the United States, who often had American-born children, for simply requesting public assistance. During the Great Depression, local relief officials worked with the immigration service to coordinate forced removals of dependent Mexicans and Mexican Americans. While many European immigrants faced scrutiny for applying to social services in the 1930s, they were not as stigmatized or penalized by it as Mexicans and Mexican Americans were.

The mass repatriation of Mexican and Mexican Americans went virtually unchallenged, but Hoover’s executive order faced mounting criticism from European American advocates. Many welcomed the LPC executive order to alleviate the impact of the Great Depression but recommended slight adjustments to help family members and “some exceptional persons.”

Related: US visa denials skyrocket under ‘back door’ public charge rule change

Under pressure, the State Department issued a memorandum instructing its consuls abroad to review all cases in which they had refused visas to relatives of citizens and resident aliens on LPC grounds and reverse their decision where appropriate. By 1934, they rejected less than 2% of relatives applying to reunite with their family members in the United States, and family reunion accounted for 60% of admissions that year alone. This decision contributed to the formalization of family reunion as a cornerstone of US immigration policy later in the century.

Though ostensibly aimed at ensuring immigrants to this country could support themselves, the LPC clause has long been used to keep out the unwanted immigrants du jour. The primary goal of restrictionist legislators at the turn of the 19th century was to preserve white, Anglo-Saxon, protestant dominance. Contrary to what USCIS acting director Cuccinelli said this week, eastern and southern Europeans were not always “desirable” immigrants.

A provision originally a response to the arrival of “new” European immigrants evolved into a tool that not only overwhelmingly penalized immigrants of color, but also received support from descendants of the original target of the LPC clause. Many chose to endorse it because they believed it would help them shed the label of undesirability. Cuccinelli’s proposed rule — and historical amnesia about his own ancestors — comes out of this tradition.

Maddalena Marinari teaches history at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota. She has published extensively on immigration restriction and immigrant mobilization. She is the author of Unwanted: Italian And Jewish Mobilization Against Restrictive Immigration Laws, 1882-1965 and a co-editor with Maria Cristina Garcia and Madeline Hsu of A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered: US Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965.