As United States’ ‘Remain in Mexico’ plan begins, Mexico plans to shut its ‘too successful’ humanitarian visa program

Migrants, part of a caravan travelling to the US, make a human chain to pull people from the river between Guatemala to Mexico in Ciudad Hidalgo and continuing to walk in Mexico, in October 2018. Many migrants headed for the border will likely find themselves waiting in Mexico as part of the US’s new “remain in Mexico” policy.

As the United States moves to implement a new plan to turn back legal asylum-seekers at the US-Mexico border, tens of thousands of Central American migrants could be stranded in Mexico while their cases are decided, which often takes a year or more.

The policy, officially called the Migrant Protection Protocols and widely known since last fall as “Remain in Mexico,” was first announced by Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen on Dec. 20. The plan goes into effect Friday, according to a Congressional aide. It’s the most drastic measure yet in President Donald Trump’s crackdown on unauthorized immigration and the most sweeping change to the US asylum system in decades. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration appeared split on the policy after it was officially announced last month: the foreign ministry reluctantly accepted it as the immigration authority publicly opposed it.

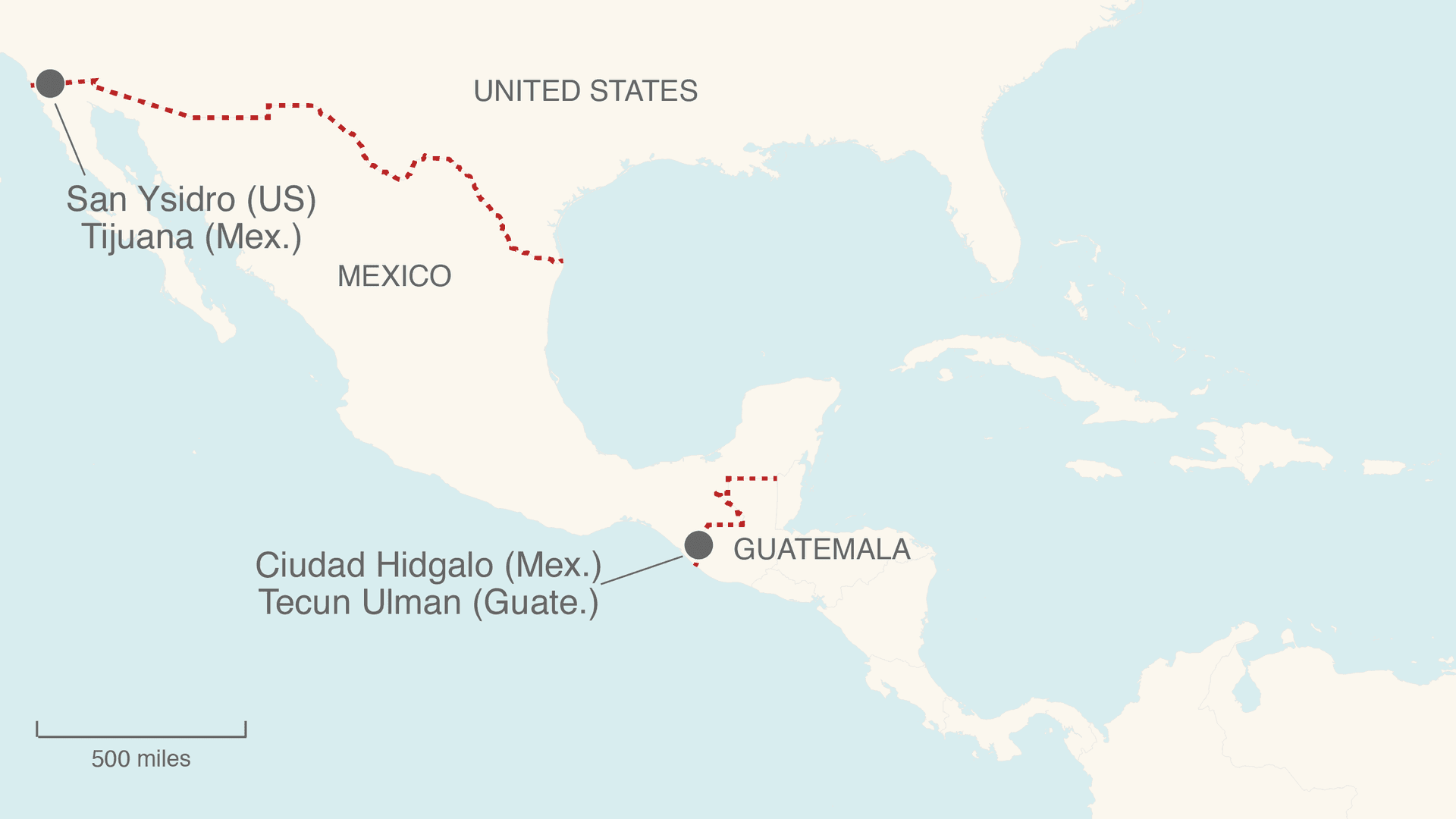

Many details are still unclear. But the policy sends people back to Mexico who are legally exercising their right to seek asylum after they’ve stepped on US soil — whether crossing at ports of entry or between them — and orders them to return to the US for a first court date within 45 days, Vox reported. It is set to be piloted Friday at the San Ysidro port of entry with an initial group of asylum-seekers being returned to Tijuana, according to news reports. A legal challenge by immigrant rights’ groups is virtually guaranteed.

Like several other Mexican officials, Tonatiuh Guillén, head of Mexico’s immigration authority, said he was not formally notified of the policy.

“This could create a crisis, especially in Tijuana, which is already overwhelmed. But it depends on the amount of people we are really talking about. … This is a US initiative, and I guess we will have to try and implement it in the most civilized way possible and in accordance with Mexican laws.”

“This could create a crisis, especially in Tijuana, which is already overwhelmed,” Guillén said. “But it depends on the amount of people we are really talking about. … This is a US initiative, and I guess we will have to try and implement it in the most civilized way possible and in accordance with Mexican laws.”

The policy also comes head-to-head with a recent effort by Mexico to grant renewable, one-year humanitarian visas to many of the roughly 13,000 Central American migrants who have accumulated at the country’s southern border.

The visas will allow them to live, work, access services, and travel freely around Mexico. Initially meant to diffuse potential chaos while the Mexican government figured out how to handle the newest wave of Central Americans, the program would be closed “shortly,” Guillén said — a decision unrelated to the United States’ move but rather because the program was “too successful” and could “overwhelm” Mexico’s immigration system. Instead, he said, the government was exploring potential employment options for people, especially in southern Mexico. On Wednesday, Interior Minister Olga Sánchez Cordero extended work permits, previously granted only to Belizeans and Guatemalans, to Salvadorans and Hondurans in seven southern states to incentivize migrants to stay.

But visas will still be given to the more than 12,000 people who have already applied since Jan. 17, Mexican immigration authorities said. Almost 80 percent of applicants are from Honduras, where small groups have continued to depart in recent days as news of the visas spread and seemed to incentivize some of them to migrate.

Most of the migrants intend to head for the US, a fact Mexican officials have acknowledged. The “remain” policy could force asylum-seekers to wait in dangerous, cartel-controlled Mexican border towns, notorious for high homicide rates, for up to a year. The US faces an immigration court backlog of more than 800,000 cases.

Just days before Nielsen announced the policy last month, two Honduran teenagers waiting to seek asylum in the United States were killed in Tijuana. Thousands of migrants from a caravan last fall have waited there as the US has slowed processing at the San Ysidro port of entry to just a few dozen per day, a practice known as “metering.”

Related: After two boys’ murders, migrants fear new ‘remain in Mexico’ policy

“The irony of this measure is that it is going to drive people who are trying to apply for asylum at ports of entry and do things the right way into the mountains and deserts. This is another way to try and limit access to US asylum system rather than try to fix it.”

“The irony of this measure is that it is going to drive people who are trying to apply for asylum at ports of entry and do things the right way into the mountains and deserts,” said Andrew Selee, president of the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, DC. “This is another way to try and limit access to US asylum system rather than try to fix it.”

“A due process disaster”

Migrant advocates in the US have warned for weeks that a “Remain in Mexico” policy would endanger asylum-seekers by forcing them to wait months or years as their cases are decided, Human Rights First on Thursday called it “illegal, immoral and inhumane.” The American Immigration Lawyers’ Association has called it “a due process disaster.”

“This plan will prevent most, if not all, returned asylum seekers from receiving a fair day in court,” AILA wrote in a policy brief last month. “Individuals forced to remain outside the US will encounter substantial barriers to accessing US attorneys — representation that can make the difference between life and death.”

Related: This busy LA immigration court is now a ‘ghost town’ in wake of government shutdown

Mexico, for its part, has said previously it would not accept the return of asylum-seekers who may face a “credible” threat back home, though there have been few details on how that might be determined. The policy will not be applied to vulnerable groups, such as unaccompanied minors or pregnant women, according to news reports.

In the meantime, Mexican authorities worried about the influx of new arrivals, many of whom say the visas drew them to migrate from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and other Central American countries in the first place.

“Especially after [Mexico] just gave all those humanitarian visas out, this new policy could create total disorder,” said Cesar Palencia, head of migrant services in Tijuana. “What are we going to do with all the people they just let in?”

During his campaign, López Obrador — who took office Dec. 1 and is known in Mexico by his initials, AMLO — pledged to institute a more humane migration strategy than that of his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, whose administration had come under fire for its treatment of migrants, which included lengthy detention times. Under Peña Nieto, Mexico began to deport more Central Americans than the United States did on a yearly basis. The country also received substantial US funding for border security and was criticized as doing the bidding of its northern neighbor.

The humanitarian visa program had been part of AMLO’s immigration policy shift, as is the rollout of his “Marshall Plan” for Central America, which is supposed to pump an extra $20 billion over five years to create jobs in southern Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. Poverty and unemployment remain top drivers of migration from the region along with high levels of corruption and gang and state violence. AMLO’s administration has yet to specify its logistics and sources of funding. But as seen with Mexico’s acceptance of “Remain in Mexico,” he has signaled willingness to work with the United States to reduce the flow of migrants.

What a “too successful” program looks like

Though Mexico’s humanitarian visa program is not new, authorities scaled it up dramatically to handle the caravan and subsequent influx. In the first three weeks of 2019, the number of visa applications has already surpassed the number granted last year. Of the 118,285 Central Americans apprehended last year, 8,865, or 7.5 percent, received humanitarian visas, according to the Mexican government, and only 0.4 percent, or 500 people, received one in 2014.

So far in 2019, just 1,210 visas have been granted over more than 12,000 applications, creating a bottleneck as throngs of migrants sleep in any space they can find on the Guatemalan side of the border and the no man’s land on the bridge between the two countries. The wait time to even register for a visa is more than 24 hours, advocates say. Officials have had to start limiting water and food handouts.

Jeisen Urbina is just one of an estimated 14,000 Central Americans migrants who arrived at Mexico’s southern border in the past week. The 22-year-old Honduran taxi driver was part of a caravan of about 2,000 that set off from the San Pedro Sula bus station in northern Honduras earlier this month.

It was his second time traveling with a caravan. In October, Urbina flung himself into the Suchiate River that divides Guatemala and Mexico as riot police in front of him launched tear gas at thousands of migrants who had pushed through the border fence behind him, determined to reach the United States. Just three months later, he stood calmly eating a bag of peanuts in the same spot on the bridge.

“Well, this is different,” he said, eyeing the water below. He waited for his brother to arrive before approaching Mexican immigration agents guiding Central Americans through the process of getting a humanitarian visa. There were no riot police, border agents, or closed gates — just an ever-growing mass of people waiting in the hot sun to get legal documents.

He had traveled more than 2,700 miles with the last caravan that arrived in Tijuana, Mexico, in November. But after speaking with immigration attorneys, he decided to return to Honduras to gather more documents that would strengthen his claim for US asylum. Urbina said he was facing threats after gang members killed his 16-year-old brother.

Now, with the US policy, Urbina’s chances to enter the US as a legal asylum-seeker may be even narrower.

Tania Karas contributed to this report.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?