Prince Hisahito, accompanied by his parents Prince Akishino and Princess Kiko, poses for photos at Ochanomizu University junior high school before attending the entrance ceremony in Tokyo, Japan, on April 8, 2019.

When Japan’s youngest prince, Hisahito, visited Bhutan in August on his first overseas trip just months after his uncle Naruhito became emperor, his trip was regarded as the debut of a future monarch on the world stage.

Greeting his hosts in traditional hakama kimono and trying his hand at archery, the visit was rare public exposure for the boy on whose shoulders the future of the monarchy rests.

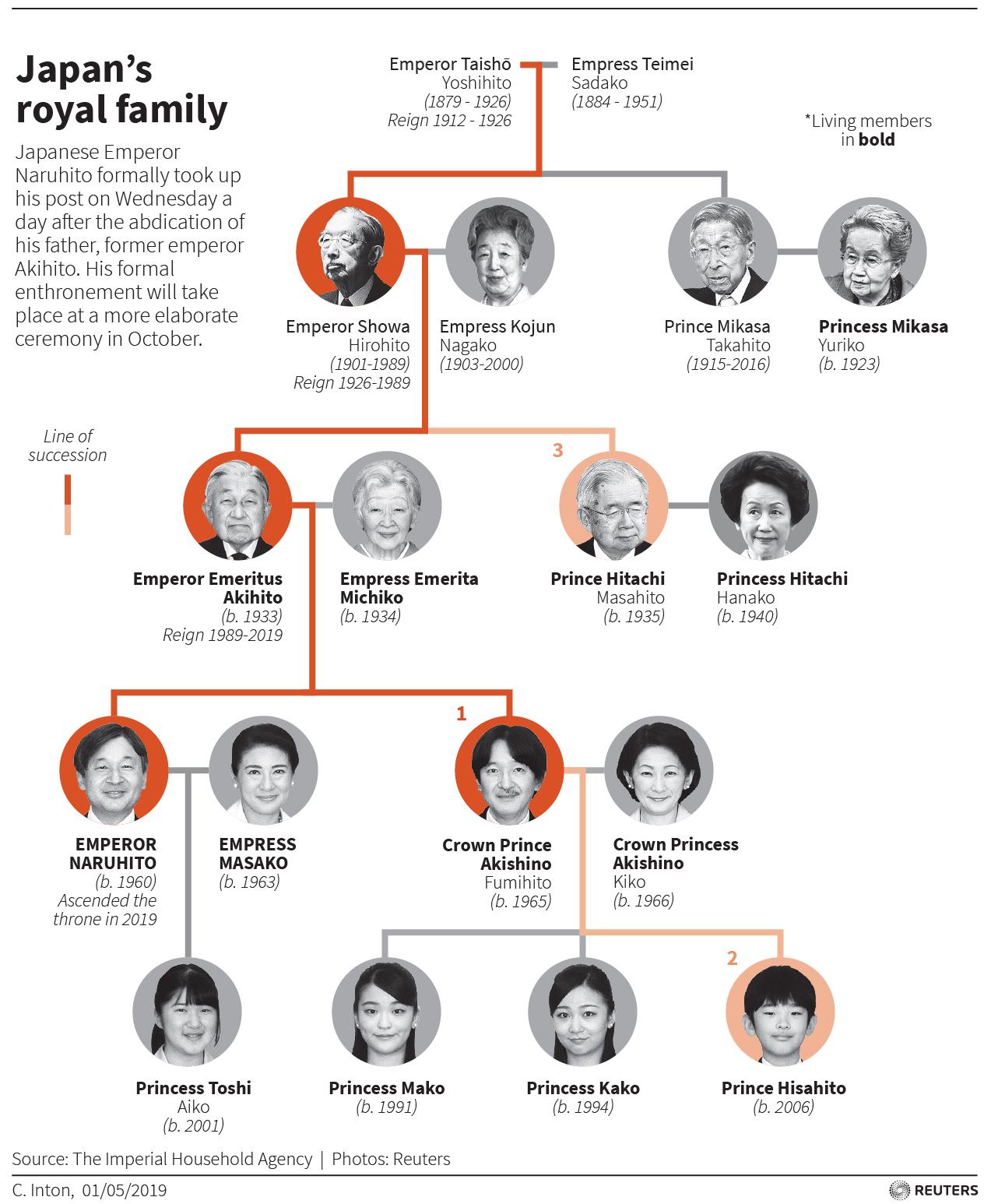

Emperor Naruhito, 59, who became monarch on May 1 following the abdication of his father, Akihito, has proclaimed his enthronement in an Oct. 22 ceremony before foreign and domestic dignitaries.

Related: Japan’s next emperor is a modern, multilingual environmentalist

Japan only allows males to ascend the ancient Chrysanthemum Throne and changes to the succession law are an anathema to conservatives backing Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Hisahito, 13, the lone royal male in his generation, is second in line to the throne after his father, Crown Prince Akishino, 53, the emperor’s younger brother.

“Under the current rules of succession, Prince Hisahito … will eventually bear the entire burden of perpetuating the imperial family. … The pressure this prince would eventually come under is too formidable to contemplate.”

“Under the current rules of succession, Prince Hisahito … will eventually bear the entire burden of perpetuating the imperial family,” the Asahi newspaper said in an editorial this year.

“The pressure this prince would eventually come under is too formidable to contemplate.”

Hisahito’s birth in 2006 was seen as a miracle by conservatives eager to preserve the males-only succession.

No imperial males had been born since 1965 and after eight years of marriage, the emperor’s wife, Masako, gave birth to a girl, Princess Aiko, spurring moves to revise the succession law and let women inherit and pass on the throne.

“Conservatives felt that the will of heaven had been revealed.”

But Hisahito’s birth put those moves on hold. “Conservatives felt that the will of heaven had been revealed,” said Hidehiko Kasahara, a professor of political science at Keio University.

Related: In stunning move, Thai king’s sister running for prime minister

Royal role, imperial succession

Now, some experts and media are wondering whether Hisahito is being properly groomed for the future.

“It is important to have him realize that he is in a position to inherit the throne when interacting with people and to keep them in mind, from an early age,” Kasahara said.

Japan’s post-World War II constitution gives the emperor no political authority and designates him as the “symbol of the state and of the unity of the people.”

Hisahito is attending a junior high school affiliated with Ochanomizu University, making him the first imperial family member since the war to study outside the Gakushuin Junior High private school.

Unlike his grandfather, Akihito, who carved out an active role as a symbol of peace, democracy and reconciliation with victims of Japan’s wartime aggression, Hisahito has no special mentor to help him prepare for his future kingship.

Akihito was mentored by Shinzo Koizumi, a former president of Keio University, among others, and then became the role model for his son, Naruhito, scholars say.

“It is necessary to have someone who can determine with him what is appropriate for a 21st-century monarch.”

“It is necessary to have someone who can determine with him what is appropriate for a 21st-century monarch,” said Naotaka Kimizuka, an expert in European monarchies at Kanto Gakuin University in Japan.

“But it is not clear to what extent Crown Prince Akishino or the Imperial Household Agency is seriously considering that.”

Whether Hisahito bears the full responsibility for continuing the imperial line is as yet unclear.

When parliament passed a special law allowing Akihito to abdicate in 2017, it adopted a non-binding resolution asking the government to consider how to ensure a stable succession.

Related: For the first time in 200 years, a Japanese emperor will give up his throne

One option is to allow females, including Aiko and Hisahito’s two elder sisters, to retain their imperial family status after marriage and inherit, or pass the throne to their children, which surveys show most ordinary Japanese favor.

Conservatives want to revive junior royal branches stripped of imperial status after the war.

Abe, though, is unlikely to want any thorny discussions. “They want to put off debate as much as possible,” Kasahara said.

Is Japan’s imperial future … female?

Japanese Emperor Naruhito formally proclaimed his ascendancy to the throne on Tuesday, Oct. 22, in a centuries-old ceremony attended by dignitaries from more than 180 countries, pledging to fulfill his duty as a symbol of the state.

“I sincerely hope that Japan will develop further and contribute to the friendship and peace of the international community and to the welfare and prosperity of human beings through the people’s wisdom and ceaseless efforts,” Naruhito said.

Naruhito is the first Japanese emperor born after World War II. He acceded to the throne when his father, Akihito, became the first Japanese monarch to abdicate in two centuries, worried that advancing age might make it hard to perform official duties.

Naruhito was revealed standing in front of a simple throne, dressed in burnt-orange robes and a black headdress, with an ancient sword and a boxed jewel, two of the so-called Three Sacred Treasures, placed beside him.

Naruhito is unusual among recent Japanese emperors since his only child, 17-year-old Aiko, is female and cannot inherit the throne under the current law. Unless the law is revised, the future of the imperial family for coming generations rests on the shoulders of his nephew, 13-year-old Hisahito, second in line for the throne after his father, Crown Prince Akishino.

Naruhito’s grandfather, Hirohito, in whose name Japanese troops fought World War II, was treated as a god but renounced his divine status after Japan’s defeat in 1945.

Some Japanese citizens rejected the elaborate displays of imperialism.

Related: There are 28 other monarchies in the world

“The emperor is necessary now as a symbol of the people, but at some point, the emperor will no longer be necessary. Things will be just fine without an emperor, said Yoshikazu Arai, 74, a retired surgeon.