Finding resistance in fashion, Kashmiri creator turns to the pheran

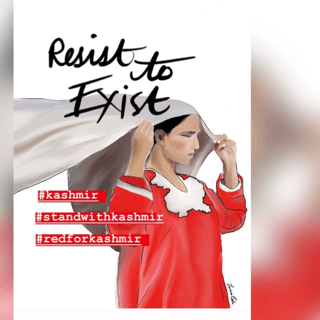

Sumaya Teli stands in Boston, Massachusetts, holding an image of a woman in a red pheran, a traditional piece of Kashmiri clothing that has become a symbol of resistance.

On Aug. 5, New Delhi revoked special rights for Indian-administered Kashmir. Since then, the internet and phone connections have been limited, and thousands have been arrested. Altercations between security forces and local Kashmiris have been frequent.

But it is not only Kashmiris in Kashmir who are resisting India’s ongoing lockdown in the region. For Sumaya Teli, a British Kashmiri writer living in Boston, Massachusetts, resistance takes on the form of fashion. Teli is using the pheran, a traditional piece of Kashmiri clothing, to bring awareness to the situation in Kashmir.

It’s not the first time the pheran has been in the spotlight as a point of resistance. In 2018, officials in Indian-administered Kashmir issued restrictions on the pheran for employees in the education department. Seen by some as an attack on Kashmiri identity, the ban provoked a social media response and was soon reversed. In 2014, the Indian army sparked outcry by telling journalists to refrain from wearing the traditional piece of clothing while visiting a corps headquarters in Srinagar, the summer capital of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. That directive, too, was revised.

The World’s Marco Werman spoke with Teli about the pheran and the image that has inspired resistance across the world.

Related: One month after crackdown, protests continue in Kashmir

Marco Werman: You’ve been writing and photographing the pheran, a traditional piece of Kashmiri clothing, and one of your images has become the face of the Kashmiri resistance movement. What is the pheran? How would you describe it?

Sumaya Teli: A pheran is the most traditional form of Kashmiri clothing. It’s worn by both men, women and children alike. It’s a warm, enveloping tunic-type clothing, but with pockets. The pockets are the best part. I have memories of my grandmother and she would always have something great that would come out of a pocket at just the right time. You know, like a piece of candy, a little coin for me or my favorite was the dried coconut. I have loved always wearing it. I’m not just wearing it today because we’re doing this talk on Kashmir. I wear it all the time.

Sumaya, you created this image of a woman in a red pheran and holding an unraveled scarf. Aug. 5, of course, is the day that India decided to take away the limited autonomy of Kashmir. Where did you first get the idea to create this image? Why was that important at this moment?

I felt like I had to do something. I had to do something other than just cry because that’s what we all felt like doing. My sister was actually visiting me from the UK [United Kingdom]. She’s a dentist, but she’s an amazing artist. We had no idea this was going to happen. When this all blew up, what I could do in my limited capacity was just go to art. I woke my sister up actually. It was very late. She was just about to go to sleep. We’d put all the kids to bed and I just woke her up. I said Zarina [Teli], you have to do this, you have to do this. And so this is a piece of digital art she did on her iPad.

The image actually is inspired by a photograph that I took of a Kashmiri woman wearing a pheran that was designed by Kashmiri women, and I, as a Kashmiri woman, felt important that I documented and photographed it. The image is a woman in a red pheran and instead of the traditional embroidery, she has a map of Kashmir embroidered on that neckline. I created the image to be used for the Kashmiri freedom struggle. It wasn’t something I just did for myself. Then I started seeing images of it being used in protests around the world, which started cropping up in waves after Aug. 5. I’ve seen it being used in banners, placards, infographics. Especially moving for me was when I saw it in banners. All across the world — I saw it in Pakistan, in Australia, in Europe, places in the UK, Denmark everywhere. I’ve seen this in North America, Canada.

Related: Kashmir conflict ‘stakes are high for the whole world’ says former ambassador

So it’s really caught on, but I gather not everybody’s embraced it. What happened when Hindu nationalists got ahold of this image?

The right-wing Hindu nationalist group took this image and really violated it, in a way. They colored her shawl into the Indian flag and Hindu-ized her by putting the red bindi on her forehead. Sorry, this is quite emotional for me, because it was quite triggering for a lot of us to see that because it was a direct, visual sort of representation of what India does to us — does to Kashmiris. The way that India tries to appropriate and erase our identities. This was just a direct visual representation of what that is.

Related: Kashmir conflict is not just a border dispute between India and Pakistan

Do you think you feel more comfortable than other Kashmiris to speak out? You’re based here in Boston. You’re not in Kashmir.

Yes, absolutely. I have a very good friend who has just returned from Kashmir and she’s quite vocal in her activism of Kashmir. And she was about to do a radio interview just like this for a UK-based radio station. Twenty-four hours before she had to start, she got to know that her father had been forcefully taken away from home and aggressively questioned about his daughter’s whereabouts and about her work. She called me in tears saying, “Sumaya, I can’t do the interview because this is about a matter of survival for me.” And she said, “Please use your privilege, you know you can raise your voice.”

And that is true. My family is in Kashmir, but my parents, my sisters, they live in the UK and I have that degree of comfort for that. But all my husband’s family are there, his parents his brothers, everyone. But we were told, even before talking, we were made very aware that we could not say anything political or ask about anything politically. Otherwise, we would put them in jeopardy. These phone calls are definitely being monitored.

Related: The story behind the iconic image of the Sudanese woman

For you, for Kashmiris in general, is independence and freedom the end game?

The irony is that people inside this open-air prison of Kashmir cannot see this image, you know, that we’ve just been talking about. It’s so representative of them. I don’t want people to get under the impression that we’ll be celebrating once this blackout is over. What I really want to say is, ask the Kashmiris — and you need to listen to them — because that has not happened in the past seven decades.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Editor’s note: In the on-air version of this story, The World reported that some communications were coming back online. There are only sporadic landline and mobile phone connections in some parts of Kashmir. For people who are trying to connect with friends and family, it’s still extremely challenging.