Colombia’s peace process under stress: 6 essential reads

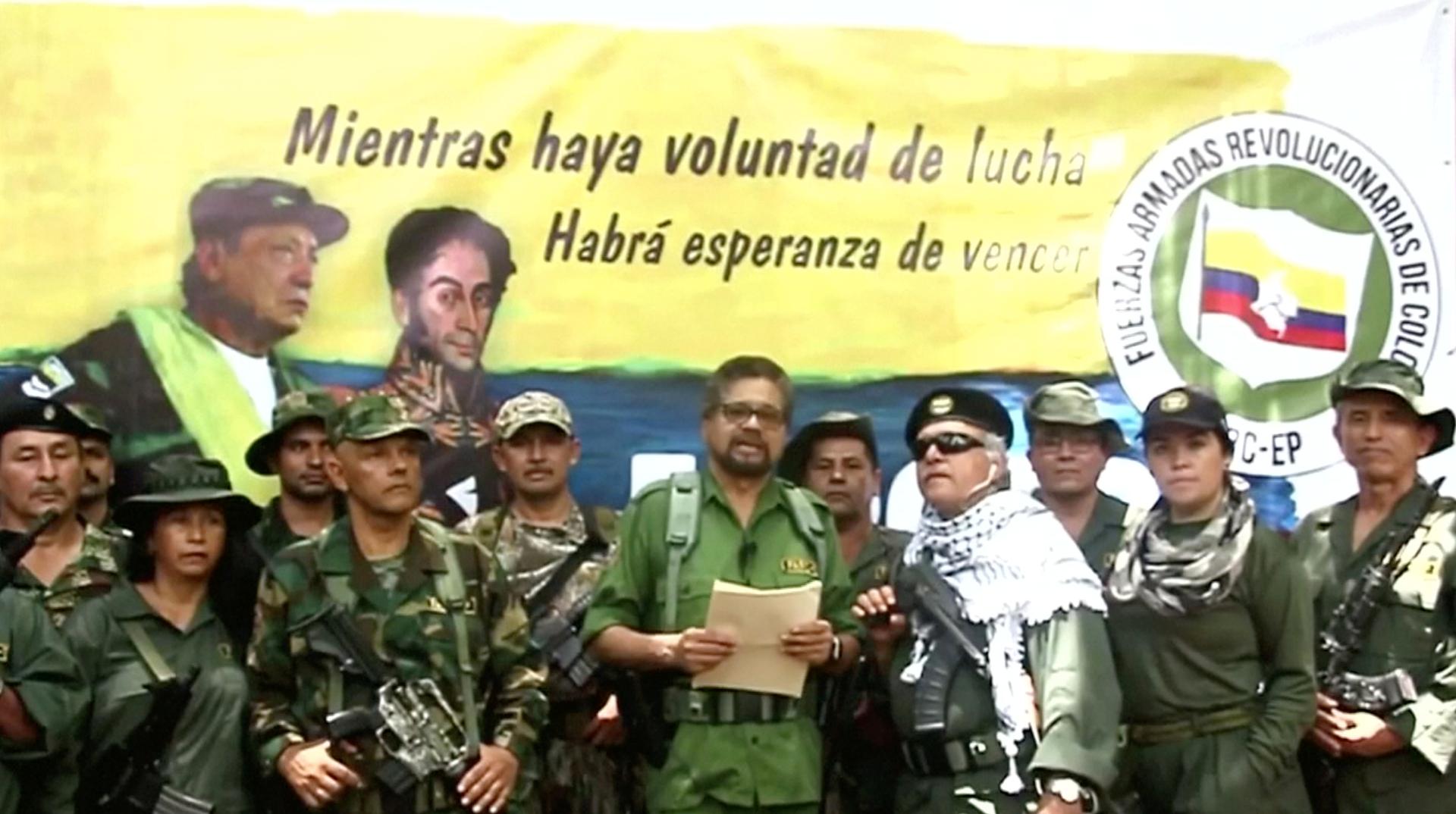

FARC commander Iván Márquez issued a return to armed struggle in a video posted Aug. 29, 2019.

Three years after negotiating a landmark peace agreement with the Colombian government, a top commander of the now-defunct FARC guerrilla group has called for “a new stage in the armed struggle.”

In a 32-minute online video posted Aug. 29, FARC second-in-command Iván Márquez appeared with other rebels in fatigues to announce that their dissident FARC faction would renew its insurgency.

“The state has not fulfilled its most important obligations,” Márquez said, saying the group aims to install a new government in Colombia that will support peace.

He does not represent all former FARC guerrillas. The FARC’s top commander, Rodrigo Londoño, who briefly ran for president last year, tweeted that “more than 90% of ex-guerrillas remain committed to the peace process.”

“War cannot be the destiny of this country,” he wrote.

How did Colombia’s fragile peace unravel? These six stories will bring you up to date on the complicated peace process that ended the Western Hemisphere’s longest-running conflict.

1. A model agreement

Peace talks with the FARC guerrillas began in 2012. In September 2015, then-President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño announced that they had developed a plan to end a 52-year conflict that had killed 220,000 Colombians and displaced 7 million.

The deal was “precedent-setting in several ways,” wrote professors Jennifer Lynn McCoy and Jelena Subotic.

The two sides agreed to use “new forms of restorative justice” to reach peace while “also holding perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable.” Colombia was the first conflict zone in the world to bring victims to the negotiating table.

Related: Despite the peace deal, former FARC fighters face a new war in rural Colombia

In exchange for laying down their weapons, FARC leaders determined not to have committed human rights violations during their armed struggle would be given amnesty and the right to run for office.

But guerrillas accused of “grave human rights crimes … like sexual crimes, kidnapping, torture, forced displacement and extrajudicial killing” would be tried by a special new wartime justice system, wrote McCoy and Subotic.

2. Colombia votes no

The final FARC accords, signed on Sept. 26, 2016, had to be approved by the Colombian people. That referendum — the “peace plebiscite” — would divide the nation.

The allure of reconciliation in a war-torn nation was clear. But some people simply could not conceive of making a deal with the rebels who had killed their friends and family.

A well-organized “no” campaign, run by a powerful and hardline former president, formed to turn other Colombians against the deal.

Michael Weintraub, an associate professor at Bogotá’s University of the Andes, summarized the “no” camp’s argument like this: The deal “provides too many concessions to the FARC, essentially rewarding terrorism and human rights violations.”

Still, as Colombians prepared to vote on Oct. 2, 2016, polling suggested that they would cast their ballots for peace.

3. The ‘no’ vote wins

The pollsters were wrong.

Just over half of Colombian voters — 50.24% — opposed the government’s agreement with the FARC guerrillas.

“A cloud of uncertainty descended on Colombia,” wrote Oscar Palma, a professor at the University of Rosario, in Bogotá, shortly after the vote. “There was no Plan B for a rejection of the agreement.”

Then, five days later, President Santos won a surprise Nobel Peace Prize for his failed peace accord.

Analysts wondered if the Nobel could revive Santos’ failed efforts to end Colombia’s civil conflict.

“It is up to the president to take advantage of this moment,” Palma wrote.

Ultimately, Santos took his rejected peace accord to the Colombian Senate, which approved it in a marathon 13-hour session on Nov. 29, 2016.

4. Peace makes progress

The accord showed immediate results.

Nearly 7,000 FARC fighters laid down their weapons and joined government retraining camps. The FARC rebranded as a political party. Violence dropped markedly in 2017, Colombia’s safest year since 1975.

But half of the country still opposed the agreement. And the Santos government struggled to hold up its end of the ambitious deal, according to Fabio Andres Diaz, writing 10 months after the accord was signed.

“From underfunded mental health care for ex-combatants to setbacks in passing the laws necessary to activate components of the peace deal, the process has been fraught,” Diaz said.

The government’s lack of follow-through raised concerns early that the FARC guerrillas would lose faith.

“There are already reports that demobilized fighters are being recruited by other armed groups,” Diaz warned.

5. Duque’s election

The powerful political forces that derailed the peace referendum hadn’t disappeared with the signing of the accord. They continued to criticize the deal, agitating for a “corrected” agreement that would more harshly punish FARC militants.

In July 2018, one of the peace accord’s biggest opponents, Iván Duque, was elected president of Colombia.

Related: 9 Colombian rebel dissidents killed in bombing raid, president says

Duque, a conservative, felt the 2016 FARC accord was “too lenient and should be renegotiated,” Diaz wrote following the Colombian election. He was the only candidate in the 2018 presidential election who did not support the FARC accords.

“Reneging on the deal risks restarting the longest-running conflict in the Western Hemisphere,” warned Diaz.

6. Unraveling a fragile peace

Duque has fulfilled his campaign promise to dismantle Colombia’s peace agreement since taking office in August 2018.

Though the courts have largely blocked his efforts to send FARC guerrillas to jail, the president has found many other ways to weaken the deal, says Diaz.

Duque has appointed “no” campaign loyalists to lead the agencies tasked with implementing the Colombia peace deal, underfunded their budgets and broken promises to boost economic investment in rural areas. His administration also sought to imprison some high-level FARC commanders on drug trafficking charges.

“Under Duque’s leadership, the government’s progress in fulfilling its commitments to peace has slowed to nearly a standstill,” Diaz says.

One-third of the peace deal’s 578 provisions have not even begun to be implemented, according to Notre Dame University’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

As a result, trust between the FARC and the government has deteriorated, Diaz says. A May 2019 Gallup poll found that 55% of Colombians doubted that the government would fulfill its commitments.

By June, an estimated 1,700 former FARC guerrillas had joined one of Colombia’s many other active militant groups.

Political violence in Colombia rose sharply in 2018, with hundreds of activists and several former FARC fighters assassinated. Saying he feared for his life, FARC commander Iván Márquez went into hiding last August.

He has now returned to public view — and, it appears, to armed rebellion.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Catesby Holmes is a global affairs editor at The Conversation. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!