Marco Werman: A Cold War baby visits Putin’s Russia

Marco Werman walks across Red Square in Moscow. Behind him are the iconic colored domes of St. Basil’s Cathedral.

The past resides in the present in Moscow in a way that feels carefully curated.

Look up as you walk through the hallways of Moscow’s gleaming Metro. The decorative ceiling roses feature small details: Soviet stars interspersed with tiny hammers and sickles. In the wide public spaces, many statues of Lenin have been removed, but just enough have been studiously preserved to remind people of the intellectual prowess of the revolution — not the lethal, nasty part.

The Gotham-like Stalin-scrapers that stand around Moscow are still there: It would be a shame to raze them despite their association. I saw no statues of Stalin, though there are several around the capital and across Russia. I did see several Stalin impersonators who, for a price, will pose for a selfie. I did see a reverent statue to Mikhail Kalashnikov, but he’s a global Soviet brand that dovetails nicely with post-Soviet capitalism.

Even if you’ve never visited before, you can tell there’s been a careful thinning of historical artifacts across Moscow, only to be replaced in less than three decades with the Dick Van Dyke-like face of “the Colonel,” pedestrian-cum-brand-label shopping streets, and farm-to-table restaurants.

Related: Generation Putin

If this observation sounds like a retread of so many Westerners’ first journeys to Russia, I plead guilty. I was born in 1961, so you could say I’m a Cold War baby. I even took part in America’s quintessential program of Cold War righteousness: the Peace Corps. At the age of 22, nearing the end of the Cold War, I was sent to Togo in West Africa. I taught junior high kids how to start their own tree nurseries. It served the US well to have people like me reminding even the tiniest villages on the planet of the might and right of American values as opposed to Soviet values.

Togo in West Africa happened to be in a unique position geographically in this respect: it was a Western proxy bordered by the Gulf of Guinea on its short southern coastline, and in the 1980s, it was surrounded by three Soviet proxies: Ghana, Burkina Faso and Benin. After the Peace Corps, as a journalist based in Burkina Faso’s capital Ouagadougou, I followed Mikhail Gorbachev’s effort to open up the Soviet economy — perestroika, glasnost — and then the eventual fall of the Soviet Union. My shortwave radio was the soundtrack, squawking the emotive strains of “The Internationale” that accompanied nearly every BBC report. The shelves of the Soviet-inspired Faso Yaar supermarket in Ouagadougou only grew more sparse as even shipments of Moskovskaya vodka slowed down from the crumbling USSR.

Like some of those statues though, “The Internationale” is still around. And to hear it played in Nishny Novgorod during a military parade rehearsal for the June Victory Day celebrations was stirring and took me back to 1989. In the same way Cold War-era Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev purged icons of Stalin after his death, so might have concluded “The Internationale.” Music, if glorious and victorious enough, apparently can evade association with the nastier parts of history.

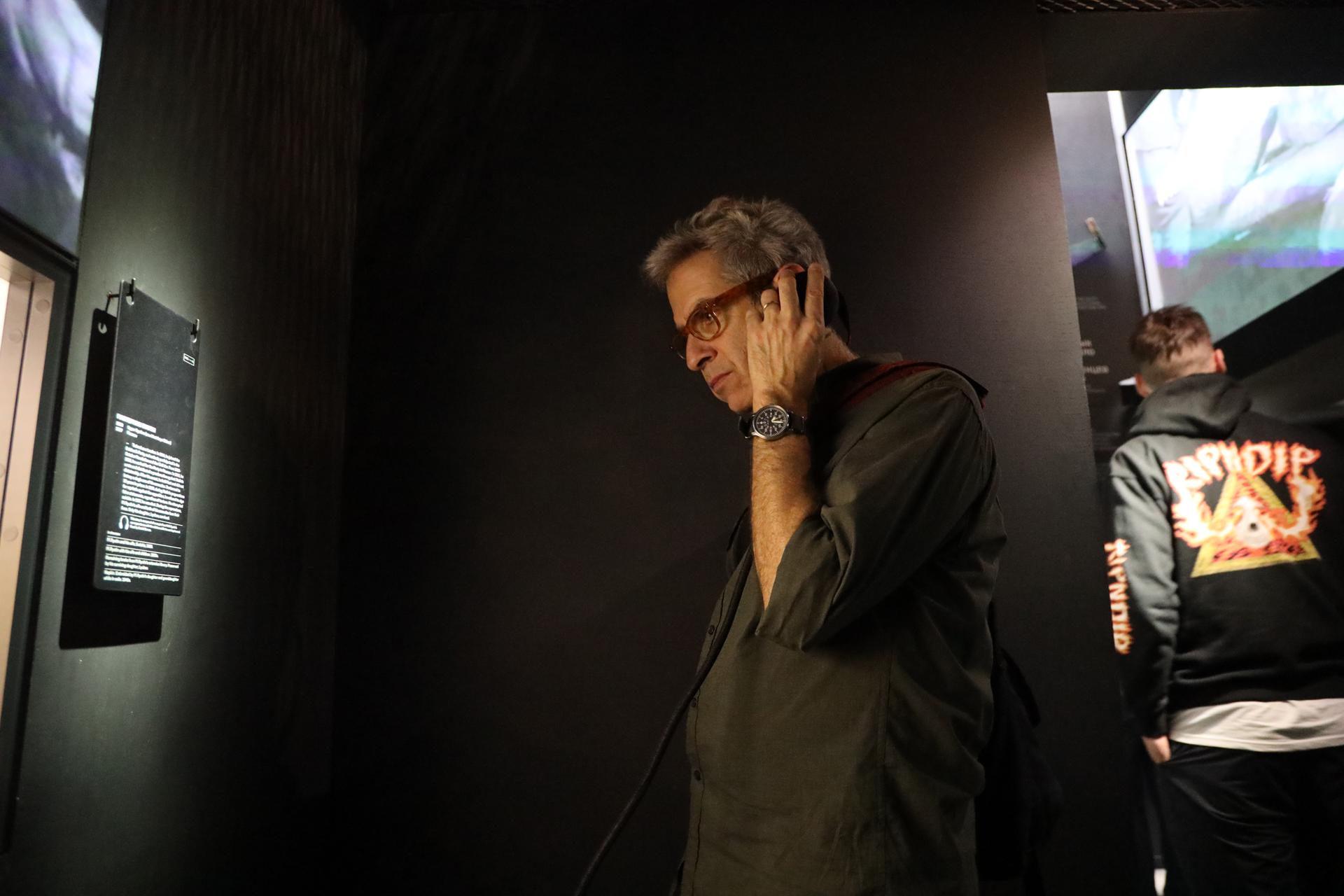

On a recent Sunday in May, I found myself on a slow-moving line of some two dozen people (mostly speaking Russian) purchasing tickets to the Gulag Museum in Moscow. Inside, guides led visitors through the dark galleries and the well-documented oral histories of a fraction of the victims of the genocidal Soviet work camps.

I was told that there used to be a video at the end of your visit to the Gulag Museum, featuring Russians who confessed knowing little about Stalin or what he did. Many of these young Russians have been taught a different story in their public schools about Stalin, one that whitewashes his savagery against the Soviet people and omits his appeasement to Hitler. Just recently, as the solemn 75th anniversary of the Normandy landing was being observed, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov burnished their narrative, throwing shade on the Allies by noting, “It was the peoples of the Soviet Union who broke the backbone of the Third Reich. That is a fact.”

The history young Russians are living through today will also be momentous, for it will either shake the status quo or it will continue to cement Putin’s narrative of near-total control of political and social life in Russia. Putin can’t technically run for president again in 2024. But that hasn’t stopped him from staying parked in the Russian executive.

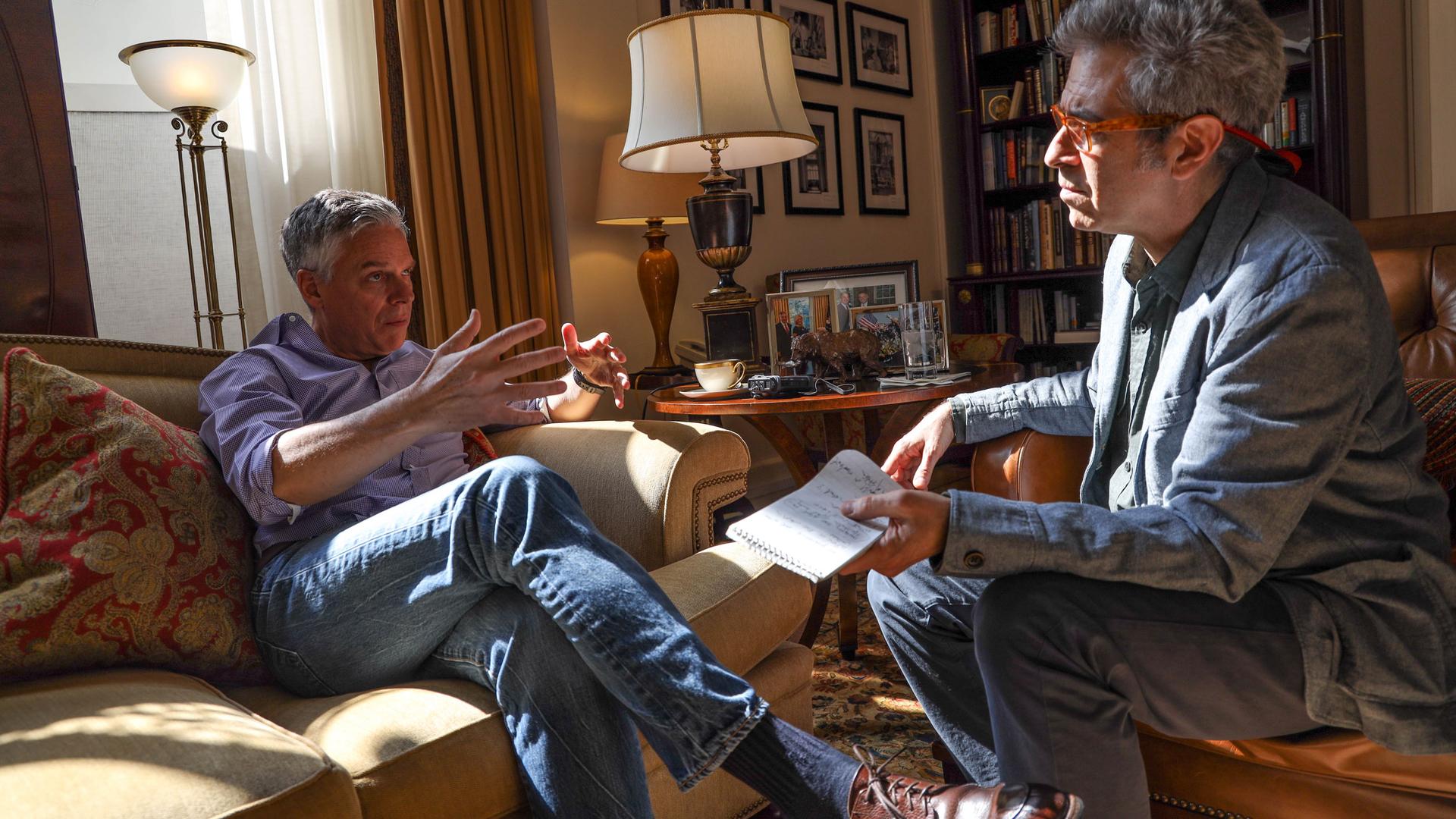

As Ambassador Jon Huntsman reminded me, Russian history is filled with seismic events that came out of the blue: 1917 and the Bolshevik revolution. The end of the USSR in 1991. The rise of Putin.

As something of a caretaker ambassador who can’t do much more than tread water through the current US-Russian frozen weirdness, Huntsman has been spending some of his extra time reading the memoirs of his predecessors. He observed that the last time things were somewhat predictable in Russia was when John Quincy Adams was president.

So what does any of this history mean to young Russians today?

I met young political activists, both pro-Putin and ones in the opposition. I met young volunteers working on behalf of victims of torture as well as volunteers finding homes for stray cats and dogs. I met feminists who are trying to get more Russians to understand the meaning of what they’re fighting for. I met young rappers who are testing the waters of what they want to say and what they think is unwise to say.

And it was odd to find myself, a non-Russian, more wired into their place on the historical timeline than some of them who are operating in the here and now. I think of those rappers who stared wide-eyed when I asked them whether they addressed any politics in their music. It was as if the thought hadn’t crossed their minds. Or the Molodiya Gvardia pro-Putin youth wing in St. Petersburg who has known only Putin their whole lives. Putin’s omnipresence meant that two of their members happily recalled wanting to be president when they were boys. This embrace of Putinism means that they can enjoy the benefits of that loyalty now and not gaze too much in the rearview.

But the ones for whom Putinism stands existentially between their beings and values — the Navalnyites, the independent press, feminists, LGBTQ activists, rappers who talk about authoritarianism and democracy, human rights activists — they understand perfectly well the past 100 years and how they figure in to a complex and history that continues to be painful for many of them.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!