Why it’s harder to win asylum, even in New York

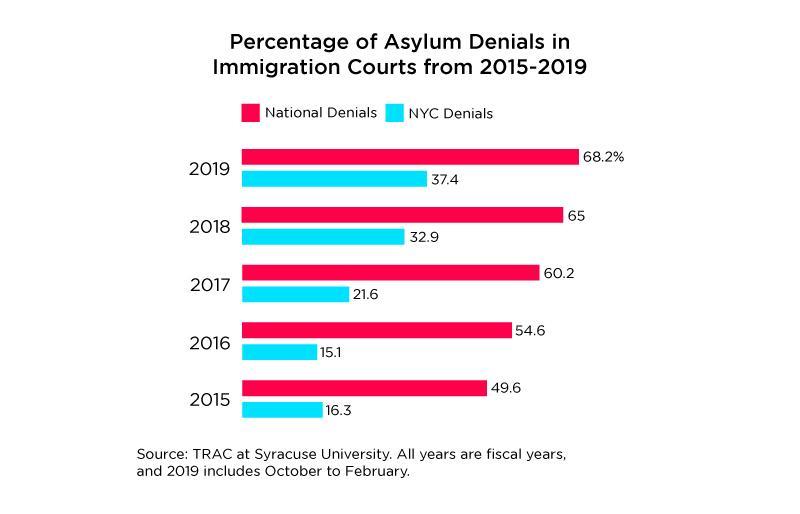

More than two thirds of immigrants, nationally, have been denied asylum so far this year compared to half who were denied four years ago. The same trend is occurring in New York City, where four years ago, just 16% of immigrants were denied asylum. Now, that figure has more than doubled, to 37% in the current fiscal year.

US President Donald Trump often claims it’s too easy for undeserving migrants to stay in the country by seeking asylum, which is why he’s reportedly been pushing for changes to the credible fear interview they undergo at the border. But fewer immigrants are receiving asylum since he took office.

According to TRAC at Syracuse University, more than two-thirds of immigrants, nationally, have been denied asylum so far this year, compared to half who were denied four years ago. The same trend is occurring in New York City, where four years ago, just 16% of immigrants were denied asylum. Now, that figure has more than doubled, to 37% in the current fiscal year.

Related: After Trump says America is ‘full,’ Vermont says ‘not us’

These local figures are based on data from the main immigration court at Federal Plaza and do not include detained immigrants who are locked up while their cases are pending.

New York has long had one of the most favorable immigration courts in the nation for asylum-seekers. In San Francisco, also known for its liberal court, the numbers haven’t changed as dramatically. Just about 25% of asylum-seekers lost their cases four years ago, compared to 31.5% today.

Immigration lawyers believe one big driver behind the trend is a decision by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions that made it harder for immigrants to win asylum based on being victimized by gang violence or domestic abuse. Sessions said these cases involve private criminals, not the government.

Related: US immigrant visa denials skyrocket under ‘back door’ public charge rule change

Immigration judges are Justice Department employees who work for the Attorney General. Sessions’ decision reversed a policy in which the judges could consider someone worthy of asylum if their government did nothing to protect them, which immigration lawyers say is common in Central American countries — especially when women want to report abusive partners.

But judges aren’t the only ones affected by this change. Immigration lawyer Sofia Dee said government lawyers, who work for the Department of Homeland Security, now ask much tougher questions of asylum seekers during their trials.

“They’re trying to attack their credibility, they’re trying to win. … As opposed to determining, like, if this person really deserves asylum or not.”

“They’re trying to attack their credibility, they’re trying to win,” she explained. “As opposed to determining, like, if this person really deserves asylum or not.”

DHS did not respond to a request for comment about whether government lawyers have shifted strategy.

Watching an asylum trial

Last month, Dee was representing a 40-year-old Guatemalan woman seeking asylum. She and her client allowed WNYC to observe the trial, which would normally not be open to the public. The trial was held inside Federal Plaza. The client asked that we withhold her name.

The woman sat with her attorney and a translator at one table, while the government’s attorney sat at another table to her left. They were all facing immigration Judge Cynthia Gordon.

Related: As judge halts US ‘remain in Mexico’ policy, returned migrants wonder what’s next

Under Dee’s questioning, the client testified that her partner started beating her when she got pregnant with their daughter 10 years ago. “He would say I was a real son of a bitch and slap me in the face and threw me down,” she testified, with the help of her translator.

“We cannot take your testimony if you are crying and upset.”

When the client started to cry, Gordon interrupted. “We cannot take your testimony if you are crying and upset,” she said, explaining that the court needed to record every word with microphones placed at each table. “The recording will only pick up the emotions, not words.”

The judge gave everyone a five-minute break for the client to compose herself. When they resumed, the woman proceeded to describe the domestic abuse she endured, and how she reported her partner to the police. At one point she sought an order of protection but later reconciled with her partner. She said she and her daughter left Guatemala three years ago after her partner was robbed by a gang.

The government attorney then picked apart the woman’s story. She asked if the man who allegedly abused her ever tried to stop her from going to the US with their daughter. The client said he did not. The attorney then grilled the woman about why she told a border agent that she feared a gang, but didn’t mention her violent partner. “I didn’t want to damage him or prejudice him so much because he’s still the father of my child,” the client replied. There were also many questions about the order of protection and missing documents.

Related: Why are so many migrant families arriving at the southern US border?

The judge asked several follow-up questions. But instead of issuing a ruling, she told both parties to submit closing arguments for her to consider over the spring.

The hearing lasted about 90 minutes and afterward the client was clearly shaken. “I was confused,” she said, adding “so many questions.”

Dee said this type of questioning was typical of the government’s approach under the Trump administration. She’s been practicing immigration law for 10 years and said she’s had a much harder time winning cases involving gang violence and domestic abuse since last year.

“You’re not excited to go to court because it’s not going to be that happy day that you’re used to having when you just changed someone’s life.”

Other immigration lawyers said they’re also having a tougher time winning these cases. “The judges will ultimately say, ‘well it’s domestic violence,'” said attorney Jake LaRaus.

Trends in asylum

It’s impossible to know how much the former attorney general’s decision on domestic violence and gangs has affected the latest numbers. The asylum rate was already dropping before last year.

Demographics have changed among those seeking asylum. Five years ago, most asylum seekers in the US were from China. Today, they’re from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras according to TRAC. In New York City, where most are still from China, there have been growing numbers from El Salvador, India and Honduras.

Related: Some Salvadoran migrants look to other nations for refuge as US tightens border

Still, Ashley Tabbador, president of the union for immigration judges, said it’s hard to ignore the obvious trends.

“Admittedly, the big surge of cases that we have seen in the recent past are coming from Central America,” she said. “And many of those cases focus on gang-related violence or domestic violence-related claims.”

But experts note that asylum rates could also be dropping if more immigrants have inherently weak cases. Many migrants are escaping poverty — which is not grounds for asylum. And some do make false claims.

Another kind of win

Recently, Dee appeared at immigration court with a Guatemalan mother who claimed she was threatened by a gang member when she tried to stop him from taking her teenage daughter. The mother and daughter made it to the US border last summer and asked for asylum.

Though they did not win their case, the judge agreed to let the mother stay in the US and work, through another type of relief for immigrants, while the daughter applies for a special form of protection available to minors. Dee said this decision was very unusual.

But her client cannot get a green card, and can’t apply to bring her other children to the US.

Dee said this decision would have disappointed her a few years ago. But after the hearing, she said, “in today’s current political climate, with the case law that we’re working with, today was a win.”