Advocates strive to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women in the US and Canada

Meskee Yatsayte, of the Navajo Nation, stands outside the Safeway in Gallup, New Mexico, with banners of missing and murdered Navajo men and women. She volunteers for the Navajo Nation Missing Persons Updates.

This story was produced in collaboration with Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines and was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Tina Russell drives along one of the main roads in Kent, Washington, about a half hour south of Seattle. She’s taking me to the place where her niece, Alyssa McLemore, used to live. We speed down a street neatly lined with suburban-style homes when we make a right turn.

She points to a peach house with Christmas lights hanging in the window.

It’s not far from where Alyssa McLemore was last seen before she went missing — a busy intersection with an entrance to state Route 167 and Interstate Highway 5 — which connects California, Oregon and Washington. It’s here that a witness saw Alyssa McLemore talking to a man in a green truck with out-of-state plates.

Related: Vancouver Whitecaps accused of mishandling abuse allegations against former coach

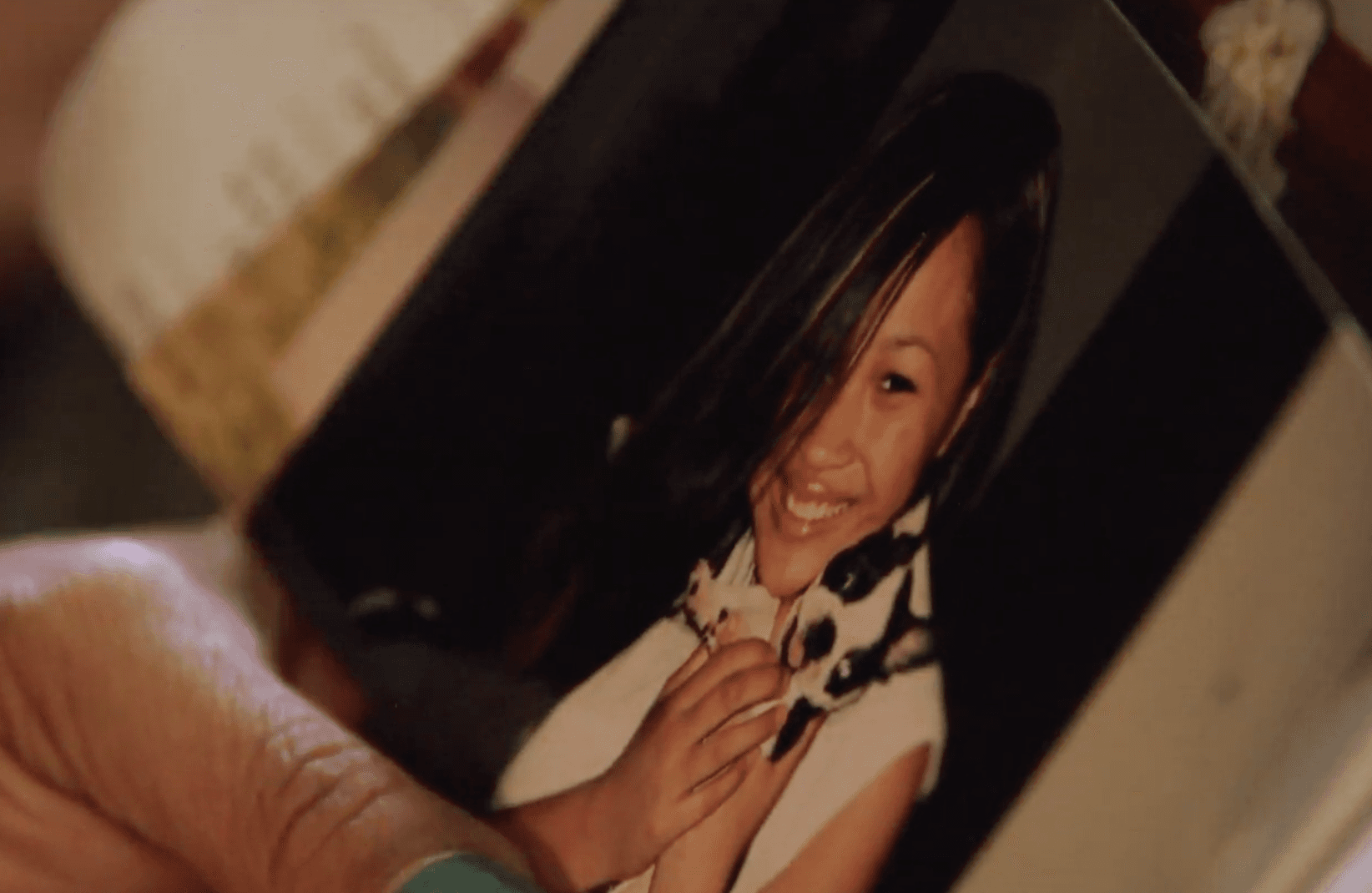

It’s been 10 years since 21-year-old Alyssa McLemore disappeared, but Russell hasn’t given up trying to find her. She keeps flyers with Alyssa McLemore’s picture tucked in a backseat pocket of her SUV, so she can hand them out at events, fairs or wherever lots of people gather. She never stops hoping someone might have seen her.

“My family needs to heal,” Russell said, wiping away tears.

“Somebody knows something, and we just need them to come forward. It can be email. It can be, you know, anonymously, or whatever. Just come forward. It’s 10 years; our family is still suffering.”

“Somebody knows something, and we just need them to come forward. It can be email. It can be, you know, anonymously, or whatever. Just come forward. It’s 10 years; our family is still suffering.”

Alyssa McLemore, a member of the Aleut tribe, is one of the thousands of Native American women nationwide who have gone missing or been murdered over the past few decades. It’s difficult to know the exact number, but the rate of violence against Native women is disproportionately high in the US and Canada. Advocates and activists in the Native community have been raising awareness, saying cases aren’t taken seriously and families continue to suffer because of racism and years of being ignored by law enforcement who should investigate these crimes.

A few days before Alyssa McLemore disappeared, her grandmother, Barbara McLemore, called her to come home — Alyssa McLemore’s mother, Gracie McLemore, was dying.

“In all the years her mom was sick, she might go away for like, a few hours,” said a soft-spoken Barbara McLemore from Russell’s living room. “But, she was always there. … She wouldn’t just go somewhere and not show up. She might be late, but she’d be there.”

Related: A UN resolution condemning sexual violence against women should’ve been uncontroversial

Alyssa McLemore never came home. Her mother died three days later.

It was a chaotic time, and the family isn’t clear on when a missing person’s report was filed. Russell says she contacted the police. But Alyssa McLemore was 21, an adult, and the local Kent police department said they couldn’t do anything for 24 hours. But when a 911 call came that week from Alyssa McLemore’s phone pleading for help, police say, they opened an investigation. So far, Russell says, it’s yielded few clues and little action.

Anytime she hears about a death on the news, she gets a sick feeling.

“Every single time there’s a body found on the news, there’s a pause. It’s literally like you’re dead for a moment because you have to wonder, ‘Is it Alyssa?’ I think I’ve called the coroner more than anybody should in a lifetime.”

“Every single time there’s a body found on the news, there’s a pause. It’s literally like you’re dead for a moment because you have to wonder, ‘Is it Alyssa?’ I think I’ve called the coroner more than anybody should in a lifetime.”

Over the border in British Columbia, Lorelei Williams’ family has a similar story. Lorelei Williams is a member of the Skatin Nation on her mom’s side and Sts’ailes on her dad’s. She’s part of a dance group called Butterflies in Spirit, which performs to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women. She also works for the Vancouver Aboriginal Community Policing Center, where she is the women’s coordinator.

Lorelei Williams’ family in Vancouver is still looking for her aunt, Belinda Williams, who is from the Skatin Nation. She went missing 41 years ago — two years before Lorelei Williams was born. Lorelei Williams says authorities didn’t open a missing person’s report until 2004. She’s not sure why, but a Vancouver newspaper says it coincided with the arrest of a notorious serial killer, Robert Pinkton. Lorelei Williams says the fact that authorities ignored her aunt’s case for years reflects racism within all areas of law enforcement.

“It’s all these systems … that are against Indigenous women and girls, and that’s why predators know that they can target us,” she said.

Lorelei Williams had a cousin, Tanya Holyk, also from the Skatin Nation, who disappeared in 1996. The family later learned that she was murdered by Pickton. Her DNA was found on his farm. Lorelei Williams says at first, Vancouver police didn’t take Holyk’s disappearance seriously, either. One officer was especially dismissive.

Related: Can First Nations Court stop Indigenous women from ending up in prison?

“She said horrible things. She said stuff like, ‘She’s just a drug addict; she’s just partying in Mexico probably. Nobody cares about her,’ and she actually told my aunt to go try to figure things out and then come back and report her [missing] again,” said Lorelei Williams.

Which meant no one was looking for her in the critical first days she went missing.

Provincial authorities later acknowledged failures in the Pickton investigation. And they launched an inquiry to determine what went wrong.

That’s not the only inquiry Canada has undergone. In 2016, Canada launched what’s known as the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, interviewing more than 2,000 families. But many, like Lorelei Williams, are skeptical that much will come of it.

The inquiry’s mandate is to look into what’s behind Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit (or LGBTQ) people going missing. One of the goals is to create a way to collect data on how many Indigenous women are going missing or being murdered. Currently, data collection neglects cultural or racial identity and gender diversity.

Lorelei Williams and others cite some of the same problems Indigenous communities in the US face — especially a lack of trust in law enforcement. Families say they were given the impression that their loved ones who were murdered or have gone missing were disposable. That’s certainly how Lorelei Williams feels: “And it really is so heartbreaking that, you know, this is our country. These are our lands, and our women are going missing and being murdered at a high rate and our own mountains are not our own territories like across the board in Canada and in the states.”

“And it really is so heartbreaking that, you know, this is our country. These are our lands, and our women are going missing and being murdered at a high rate and our own mountains are not our own territories like across the board in Canada and in the states.”

It’s not just lack of attention. Another issue in solving these cases is the lack of hard data.

Government agencies don’t have comprehensive data on how many people in the US are missing.

“We can’t solve [what] we don’t check. We can’t prevent violence that we don’t bother to pay attention to,” said Annita Lucchesi, who is Cheyenne.

Lucchesi says it seemed like no one was keeping track of these missing and murdered women. So, she figured she would. Lucchesi spoke from Berkeley, California, at the launch of the Sovereign Bodies Institute, which gathers data on gender and sexual violence against Indigenous people. She’s the executive director. She says the more she looked at what records were available, the more she realized how incomplete they were. Especially when it came to race.

“I couldn’t afford Wi-Fi. So, I was working out of coffee shops,” Lucchesi said.

“And I was sitting at a Panera, and I really thought someone had created this list. So, we assume, ‘Surely someone is doing something about it.’ [But] what I assumed was there wasn’t [there]. And I was so frustrated.”

Her work at Sovereign Bodies began as the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women database. The more she looked at what records were available on missing Indigenous women, the more she realized how incomplete they were.

“Many law enforcement agencies still don’t track race at all or don’t include a signifier for Native American with any options,” she said. “They’ll just do like white, black, Hispanic, Asian and then many of the cases that do get logged into systems are misclassified because the officer looked at someone and assumed or didn’t enter the information in and the system defaults to white.”

Lucchesi says she filed numerous records requests with law enforcement agencies across the United States. She also keeps track of missing women in Canada. The database now includes more than 5,000 names — a few going back to the early 20th century, though most are from the past 20 years. She says that number is an undercount.

Lucchesi says the database is a keeper of names. But it’s also data about Native women and girls collected by Native women and girls. And that in itself is powerful. She calls it “data sovereignty.”

She says she grew tired of hearing people say they didn’t know how to fix these problems.

“So, it becomes this excuse for people that just kind of throw their hands in the air and just say, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know,’” Lucchesi said.

“But that’s not good enough anymore. So, that’s the work of the database; that’s the work of Sovereign Bodies Institute is to say, ‘We’re not going to throw our hands in the air anymore.’”

Often when Native women go missing, she says, there is a lot of victim blaming. She says some Native women were labeled by police as sex workers putting themselves in harm’s way.

“They didn’t consent to live under colonial occupation; they didn’t consent to have their nation and their community be displaced and experience all of this horrific violence.”

“They didn’t consent to live under colonial occupation; they didn’t consent to have their nation and their community be displaced and experience all of this horrific violence,” Lucchesi said.

“So, the very way we think about these women and the choices they make is very victim blaming.”

Lack of attention or lack of data is just one problem that prevents missing and murdered cases from being solved. In the United States, there’s also the issue of jurisdiction.

When it comes to most violent crimes, tribes lack the authority to prosecute, with the exception of domestic violence.

It’s federal agencies like the FBI that prosecute those crimes.

And, that’s a problem, says Sarah Deer. She’s a citizen of the Mvscogee (Creek) Nation, a lawyer and an advocate for Native women who are survivors of sexual assault and domestic abuse.

“I think that federal Indian law has really worked as a patchwork of different laws that kind of almost contradict each other at times, which makes everything very confusing for all involved. And so, sometimes when a crime is reported in Indian country, again depending on where you are, there is no action because everyone is in disagreement about who should be in charge. And so nobody acts at all,” Deer said.

The problem goes back more than a century and has to do with the Major Crimes Act, which was passed in 1885 as part of the Indian Appropriations Act. It places certain crimes under federal jurisdiction if they are committed on a reservation.

“So, if a Native woman goes missing from a reservation and there’s any instinct that she’s been kidnapped or assaulted or has been the victim of homicide, technically, if that happens within the territory of the tribal nation, the federal government would have that authority to come in and investigate them. And eventually, if possible, prosecute the offender. Historically, what tribal nations have all complained about is that even though the federal government has the authority, sometimes they don’t respond at all.”

And when they don’t respond, families end up waiting for years for answers.

Meskee Yatsayte and her husband wanted to do something about the crisis of missing and murdered Navajo women and men. Yatsayte is a Navajo Nation citizen who volunteers for the Navajo Nation Missing Persons Updates. On the first Saturday of the month, she and her husband park their trucks on a main street in Gallup, New Mexico. Their trucks are plastered with banners that contain the faces of those who’ve gone missing or been murdered.

They’re hoping someone happening by will recognize the faces pictured or drop a clue.

Even though it’s a cold and windy day with rain clouds looming overhead, Yatsayte remains committed to giving justice to these families. She points to a few people on the banner. One of them is Leland Tso, a Navajo man and father of three. Yatsayte says Navajo men are also going missing and murdered. And she says their families deserve some peace.

Tiara Shorty, who is also a Navajo Nation citizen and is Tso’s niece, says her family is heartbroken over his murder. “He was the glue that kept everyone together,” Shorty said. “He knew what was going on. What events were going on. He knew people’s birthdays; he knew numbers by heart.”

Tso was last seen on July 4, 2016, in Wheatfields, Arizona, where Shorty’s family is from. Witnesses say he was getting into a white truck in Navajo, New Mexico, on his way back to Wheatfields. His body was found in a “wash,” a shallow creek, by a family having a picnic.

When they first got the call that Tso’s body was found, Shorty says, her mom thought it was a joke and hung up on officer Ernest Yazzie, who is currently investigating the case. Tso’s body was found on the reservation, and so far, there have been few clues as to what happened. They’ve set up a hotline and offered a reward, but so far, few leads have materialized.

Shorty knows the Navajo Nation police is short-staffed, but she is grateful for what has been done on her uncle’s case. She remains committed to getting justice for him.

In the past few years, several states have passed legislation to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women. And Savanna’s Act, named for Savanna La Fontaine-Greywind, who was killed in North Dakota in 2017, has been reintroduced in Congress to set guidelines for law enforcement agencies investigating missing Indigenous women. In Canada, Lorelei Williams plans to travel to Ottawa next month to hear the conclusions of the National Inquiry. But she’s not sure how much comfort it will bring her family.

“My family has been broken apart. It’s never been the same,” said Lorelei Williams.

As for Russell, who still carries flyers with photos of her niece Alyssa McLemore, she says her family is frozen in time.

“We don’t know what happened so we can’t begin to heal. Life goes on, but like I said, we’re just putting a Band-Aid over something that is really a stitcher’s job. You know, until we find Alyssa and bring her home, it’s going to cause generational trauma.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?