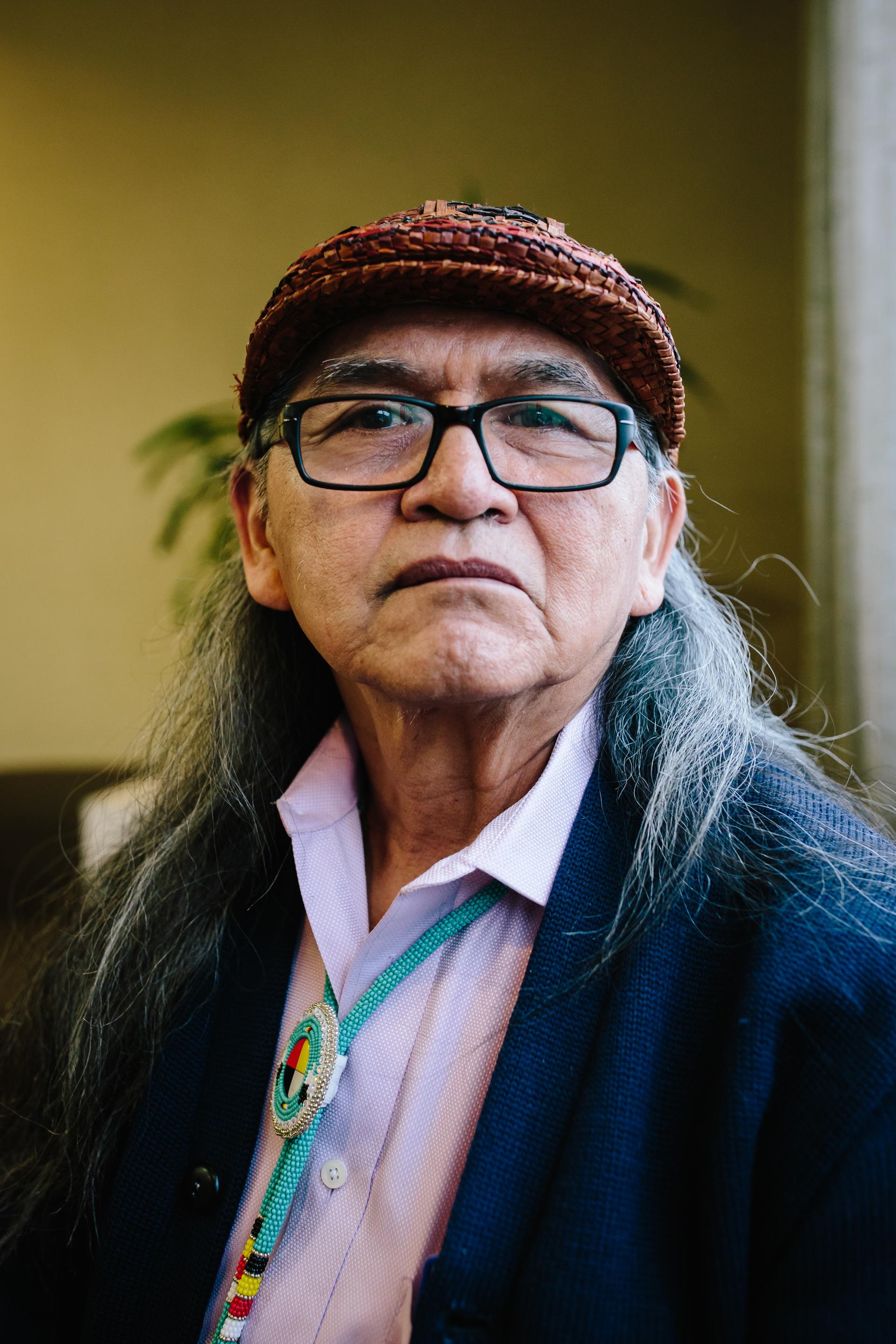

The First Nations Court's elders are pictured (left to right): Linda Williams, Darryl Baker, Doris Paul and Eugene Henry.

The woman sits with her hands clasped tightly together.

She’s petite and has long, curly, reddish hair with just a strand or two of gray. She’s still wearing her winter coat, even though it’s uncomfortably warm in the courtroom.

This woman, who asked not to be named, has come here to plead guilty to theft. She’s at the North Vancouver Provincial Court to be sentenced.

She admits that she stole hundreds of dollars of baby formula from a large supermarket chain. But before she is sentenced, she’s asked about her life — about why she stole the baby food. She explains that it was to sell, so she could buy cocaine.

She’s asked if she has a job now. She says she does. She’s asked if she’s no longer using cocaine. She says she isn’t. The judge turns to a semicircle of people sitting near the table. The judge asks if they have any questions for the woman sitting in front of them.

This is First Nations Court. And sitting next to the judge are five Indigenous community leaders.

These three women and two men come to the courthouse once a month to work in this sentencing court. First Nations Court works within the existing Canadian justice system, with offenders who have already admitted their guilt.

Linda Williams is a court elder. “They need someone to support them, to help them through the hard times,” says Williams. “I’ve been very lucky throughout my life … to me, it’s a way of giving back for the blessings that I’ve received.”

Eugene Henry is also an elder. Before court begins, he offers a prayer in both English and his Indigenous language.

“We’re working together here, hand in hand,” explains Henry. “And we do it with lots of prayer and lots of guidance. And an open mind and open heart.”

The First Nations Court’s goal is to provide a sentence for the offenders that can help rehabilitate them back into society. Judges work with lawyers, the elders, drug and alcohol counselors, and often, victims, to come up with a healing plan for the offender.

Doris Paul is an elder, and she helped to create this First Nations Court five years ago.

“We remind the ones that we’ve seen in pain, we remind them that we are here and that we believe that our culture is our healing.”

She says that she used to sit in the court gallery when members of her community, the Squamish Nation, were being sentenced.

“And I remember interrupting,” she explains. Paul would stop the judge and ask to address the court.

She would tell the judge how the community was working with the offender, and she would ask the judge to consider that in sentencing.

“Then it became a real, keen interest, you know, how does the culture play a healing part within the First Nations [people] going through court, through the justice system, law enforcement.”

The First Nations Court began in North Vancouver more than five years ago.

Anyone from the area who self-identifies as Indigenous can be sentenced here.

The court is one of a number of restorative justice courts in Canada.

It is different in some ways from a conventional court. The judge sits at a large table with the lawyers, the person being sentenced and the elders.

There are moments of tears, bursts of laughter. There’s a pat on the arm or a hug.

The woman appearing before the court today, charged with baby formula theft, is given a 12-month probationary sentence. And she’s banned from going to the store she stole from.

Outside of court, she is visibly relieved. “It was wonderful!” she says, with a broad smile on her face. “It was really heartfelt. Like, people really had compassion, affection, understanding and patience — something that you don’t get in regular court. It was like one, big family sitting there talking. Even the judge, who jumped right in there — like he was family, too.”

Indigenous adults make up about 4 percent of Canada’s population.

But Indigenous women account for 38 percent of female admissions to provincial- and territorial-sentenced custody; Indigenous men are 26 percent.

Women are often imprisoned for crimes that are linked to substance abuse.

That’s what led the woman appearing in court to steal the baby formula.

“By the time I was 15, I was an alcoholic, and no one told me that the substance abuse would carry me to a place that would be very dark and lonely; you’re sitting under a dark cloud and you can’t seem to escape it,” she says.

For so many Indigenous women, the stories are similar — the trap of poverty, the lack of educational and employment opportunities and histories of trauma.

Arlene Loyst is the crown counsel assigned to First Nations Court.

“The incarceration rate for Aboriginal women is completely out of whack,” Loyst says. “And if you look at a lot of their crimes, it’s as a result of poverty, neglect, abuse. So, if you do look at it holistically, then I do believe, which is why I am doing this, it’s more likely we can get them help and get them out of that cycle.”

Stopping that cycle of Indigenous women moving in and out of prison is one of the key objectives of First Nations Court.

Andrew Van Eden is the justice and special projects officer with the Tsleil-Waututh Nation in North Vancouver. He worked with Doris Paul and Justice Joanne Challenger to create First Nations Court. “I would say that the majority of the ones that come in accused of something, come in because they are walking in this world alone,” Van Eden explains. “They are showing up to this really scary process alone, and they are going back out with whatever the decision of the court was to walk back out in the world alone but to somehow get better — and I don’t think we find success in that approach.”

And finding success in lowering the incarceration rate for Indigenous Canadians is something that Canada’s justice minister, Jody Wilson-Raybould, says her government is working toward.

“I am a firm and avid supporter of the restorative justice measures that we currently have in Canada and want to ensure as minister that I promote and invest in more restorative justice measures across the country,” Wilson-Raybould says. “And that can range from specialized courts to sentencing circles. I think that in terms of overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the criminal court — to be able to effectively deal with individuals, to enable communities and Indigenous laws and traditions and rehabilitation measures to come into play — in terms of providing off-ramps for Indigenous peoples, [we need] to make sure as much as possible, that they do not cycle back through the justice system.”

Breaking the cycle goes beyond the courtroom. It’s crucial that the person being sentenced stays in contact with their Indigenous community, to keep from reoffending.

Paul sits in her van applying black paint made from the root of the devil’s club plant to her face.

“It protects us from what we believe is the bad spirit; then we are covered with the good spirit.”

There is a cleansing ceremony about to begin in the Squamish Nation longhouse. As an elder, Paul will be participating in the ceremony.

This is when she shares her story. Paul is a residential school survivor.

Indigenous children in Canada were taken to residential schools — government-sponsored religious boarding schools. The system was created to remove children from their own culture and force them to assimilate into Canadian culture. The schools were established in the 1880s, and the last one in Canada closed in the 1990s.

“I went to residential school; I think it was 1962, and I left in 1973. I knew right away when I got there, at the age of 6, that it was evil.”

Like the more than 150,000 children sent to residential school, Paul was forced to give up her language. She couldn’t socialize with her sisters who were at the same school. The Canadian government has acknowledged that the schools were places where many children were physically and sexually abused.

The Canadian government formally apologized for the residential school system in 2008, stating that “we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm and has no place in our country.”

The residential school system broke families — and broke Indigenous communities.

It nearly broke Paul.

“And I’m going to be very direct, very honest in this,” she says. “I was beaten so badly, at the age of 6, where I would crumple on the floor and just stay there until the pain stopped; and at the age of 9, I was raped by the priest; and I remember, at the young age of 9, trying to commit suicide because of what happened to me.”

When Paul was a teenager, she began drowning her pain with alcohol. She married a man who physically abused her. They had three children together. It wasn’t until her children witnessed a particularly violent, alcohol-fueled fight between her and her husband that she found the resolve to stop drinking.

And it was through the healing she found by reconnecting with her culture that she got her life on track. “I could go in this world and just be an angry, mean person to hurt everybody the way I was hurt but through the use of our culture, I think it’s really helped me not carry bitterness.”

Paul says that the culture is the medicine.

And for some people, the First Nations Court is the first dose.

It’s why, she says, elders often share their own stories with those being sentenced — their own experiences of residential school trauma, stories of substance abuse, losing their culture, being adrift in the world.

Ceremonies, like the one happening in this longhouse, are where Indigenous people reconnect with family, speak their common language and participate in the rituals that build a strong community.

“I can sit in this ceremony today, and I can see how many people I’ve helped through the culture,” says Paul. “And they put down the bottle, they put down the drug, the needle; and they picked up a drum and a drumstick; and they are drumming and participating in our ceremonies.

Paul snaps closed the devil’s club root paint. She’s ready for the ceremony.

“It’s really important to remind First Nations people that they come from somewhere,” she says. “That they belong somewhere.”

[[entity_id:”178614″ entity_type:”node” entity_title:”Unequal Justice series”]]