Gene therapy is a game changer for medicine — but comes with a hefty price tag

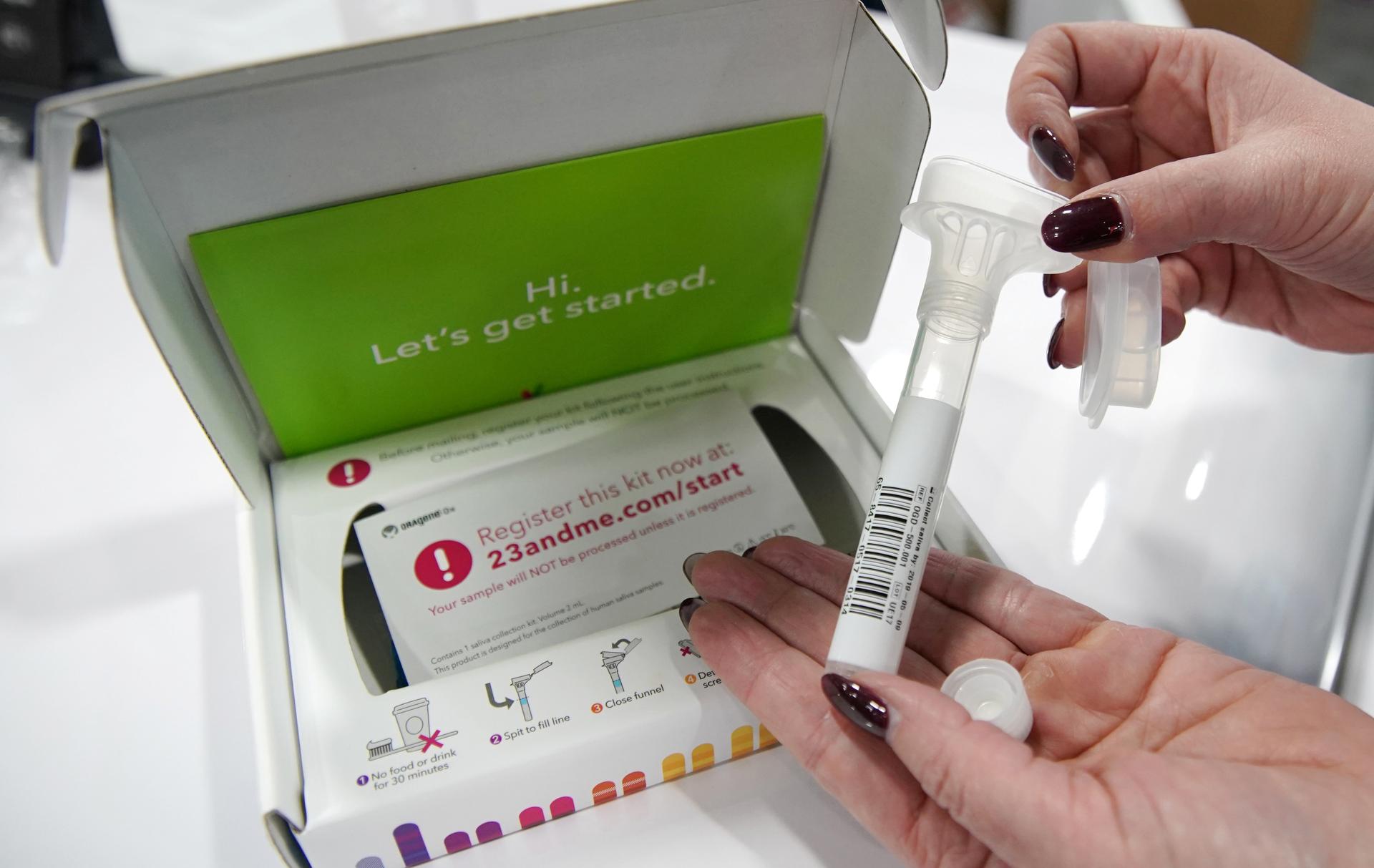

A company representative shows off the contents of a 23andMe DNA kit.

As we understand our genes better, medicine is changing in a profound way. New cures and treatments are becoming available, and preventative medicine is entering a new era. It’s been almost 20 years since the first complete map of the human genome was created and, since then, genetic tests — provided by companies like 23andMe — have gathered tons of data from people across the world.

“I think that what 23andMe has done is absolutely revolutionary, and I think really begins to democratize both access to genetic information and the ability of people to begin to manage that information,” said Carlos Bustamante, professor of genetics at Stanford University. “[It’s] turning the crank on engaging individuals so they share more information, so that we can then use it to do more and more studies.”

Genetic information may be becoming more democratized, but Bustamante is convinced that a greater diversity of information needs to be collected and studied — not just the genes of those with European backgrounds (who dominate the current data).

Related: The first genome edited babies are here. What happens next?

“If we think of data as the new oil, right, we’ve only been fishing in the North Sea,” Bustamante said. “There’s a ton of opportunity to look in other populations, and not only is it the right ethical thing to do but, from a purely scientific point of view … the evidence is that people in different parts of the world have different genetic reasons for exhibiting a given trait.”

Take diabetes, for example. Bustamante says that treating diabetes can be personalized based on our unique genetic codes. He stresses that genetic research needs to focus on people from different parts of the world, in order to make sure that everyone can benefit from individually-specialized treatments.

Another challenge — as our knowledge of genetics leads us to more effective medicines — is to make those medicines widely accessible. Antonio Regalado, senior editor of biomedicine for MIT Technology Review, explains the huge potential that gene therapy has to cure diseases, but notes the hefty cost, which can be hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient or more.

Related: Coal plant emissions damage infant DNA, a new study shows.

Gene therapy often uses components of a virus to act as a transportation system that delivers treatment to specific genes. “The reason that it costs so much is that actually producing these viral particles that you need to do the gene therapy … costs about a million dollars,” Regalado said.

Bustamante hopes that genetic treatment costs will be lowered, but also looks forward to the day when our healthcare system is more focused on prevention.

“We have a sick care system, we don’t have a health care system. That sick care system incentivizes acute care versus preventative care,” Bustamante said. “Today we really are in a position where we can use genetics to identify people at risk and put them on preventative treatments that could avert heart attacks and strokes.”

The original version of this story appeared on the Innovation Hub. Hannah Uebele is an intern at Innovation Hub.