America has been at NATO’s helm for 70 years. Can it survive without US leadership?

Banners displaying the NATO logo are placed at the entrance of new NATO headquarters during the move to the new building, in Brussels, Belgium, April 19, 2018.

NATO was born in the aftermath of World War II out of a desire to prevent World War III.

“NATO was established because there was a threat at the beginning of the Cold War of a Soviet invasion of Western Europe,” says Nicholas Burns, a former US ambassador to NATO. “The Soviet army found itself, at the end of World War II, in a very advantageous geopolitical position in Eastern Europe.

“The West European countries had largely been destroyed by World War II,” adds Burns. “If the United States and the West European countries and Canada hadn’t formed the alliance on April 4, 1949, there’s every reason to believe Soviets would have pushed further into the democracies of Western Europe, and the United States could not let that happen. So, this was a treaty in the self-interest of the United States as well as Canada and the European countries.”

The treaty was signed amid much fanfare in Washington on April 4, 1949.

Now, at 70, NATO lives in a much different world than the one that created it. One former US ambassador says the “current state of the alliance is troubled” and others point to a weakness in American leadership as a cause for concern. But it’s not the first time in history that NATO has had to redefine itself.

‘… the will of the people of the world for freedom and peace’

President Harry S. Truman, speaking at the ceremony, said: “if there is anything certain today, if there is anything inevitable in the future, it is the will of the people of the world for freedom and for peace.”

Related: NATO at 70: ‘Not anti-Russian,’ but committed to securing member states

The rhetoric was sincere. And necessary. The US had never previously had a defensive alliance in peacetime. The nation’s founding fathers had warned against foreign entanglements. That resistance continued in the 1940s.

NATO’S founding fathers, like Secretary of State Dean Acheson, had to win over the support of Congress and the American people.

“The Atlantic Pact,” Acheson said in one speech, “is a collective self-defense arrangement, among the countries of the North Atlantic area. It is a simple fact proved by experience that an outside attack upon one member of this community is an attack upon all members.”

Atchison’s argument for collective self-defense is enshrined in Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

The idea was to deter Soviet attack, and it worked.

“NATO was extraordinarily successful,” says Ambassador Burns, “because it was able to deter the Soviet Union, and later modern Russia, from thinking of a conventional attack into Western Europe. That was a real danger.”

Related: A brief history of coups in NATO nations

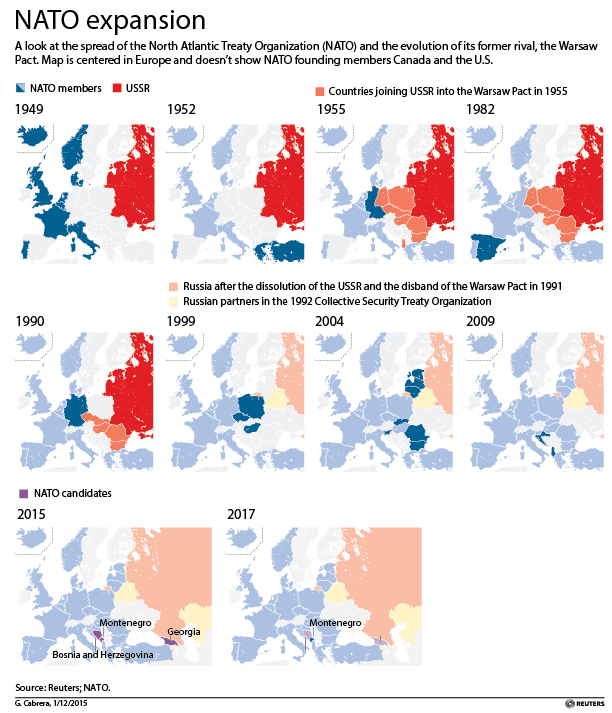

NATO expands to the east

NATO had plenty of ups and downs. There was a crisis when France withdrew from the integrated command structure in 1966. There were massive demonstrations in Europe in the 1980s as Ronald Reagan got into a new arms race with the Soviet bloc.

But after 40 years of stubborn containment of Soviet power, the whole edifice came crashing down.

The Berlin Wall — that symbol of the division of Europe — came down in 1989. The Soviet Union itself collapsed two years later.

It was a critical crossroads for NATO. Some said it should simply disband. Others said it should remain a defensive alliance. Many senior diplomats and international relations thinkers argued against expanding NATO, saying it would needlessly provoke Russia. These included Secretary of State James Baker and George Kennan, one of the original architects of the policy of containing Soviet power.

But under the Clinton administration, NATO and the European Union expanded eastward, in part to fill the power vacuum in Eastern Europe.

“This was I think one of the greatest things that NATO has ever done,” Burns argues.” It’s why NATO is relevant today, in 2019, because if we had not extended this security guarantee to East European countries, you can bet that the Russian Federation would be seeking to dominate them today. But Russia cannot.”

Not everyone agrees. James Carden, a former adviser to the State Department on Russia, says the eastward expansion of NATO is at the root of a lot of the problems today with Russia. “It became very clear toward the end of the ‘90s that Russia was not going to react very well to the idea that the alliance was going to expand right to its westernmost border.”

Many diplomats, like Ivo Daalder, another former US ambassador to NATO, believe it wouldn’t have made a difference.

“Russia is Russia,” says Daalder. ”I think the Russia we’re seeing today is not that different from the Russia we have seen over the course of history: A country somewhat insecure in its own borders and seeking security by expanding its reach to its neighboring countries.”

Daalder argues that just because NATO is about to turn 70, there’s no reason for it to contemplate retirement.

Debate about possible Russian reaction to NATO expansion was submerged by the attack on the US on Sept. 11, 2001, as focus shifted to the Middle East. That was the only time Article 5 has ever been invoked, and NATO countries leaped to help the US both in Afghanistan and globally against al-Qaeda.

Concern over Russia re-emerged with its invasion of the former Soviet republic of Georgia in 2008.

‘… the absence of strong, principled American presidential leadership’

That brings us to President Donald Trump. At his NATO debut in May 2017, Trump criticized his allies for failing to pay their way, as have other presidents. But he falsely claimed they owed the US money. Trump also failed to mention Article 5 — “the one for all, and all for one” guarantee at the heart of NATO.

“I have to say that I’m disappointed that the way that my president has treated allies is not helpful,” says Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, the former commander of the US Army in Europe. “I mean, should nations be doing more, especially Germany, for example? Absolutely they should, every president has said that. But I think there’s a better approach to doing this.”

Related: Trump’s comments leave some European leaders worried about the future of NATO

“Europe has under-invested in defense for two decades. And America is no longer leading.”

“I think the current state of the alliance is troubled,” concludes Daalder. “Europe has under-invested in defense for two decades. And America is no longer leading.”

Burns also sees problems with a lack of leadership from America.

“NATO is stronger than Russia militarily,” Burns says. “But NATO has always had a leader: The American president — from Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower and all their successors — who believed in the alliance and was credible enough that the Russians would fear that the American leader would defend the NATO countries in case of attack. That is not the case with Donald Trump.”

Burns testified to Congress last month on the current state of the alliance between America and Europe, after co-authoring a report in February on the issue.

“Our principal finding,” he says, “after having interviewed 60 officials on both sides of the Atlantic, is that the single greatest challenge NATO faces is the absence of strong, principled American presidential leadership for the first time in its history.”

“Our principal finding after having interviewed 60 officials on both sides of the Atlantic, is that the single greatest challenge NATO faces is the absence of strong principled American presidential leadership for the first time in its history.

“The fundamental weakness that NATO has now is that it doesn’t have a leader who can stand up to Vladimir Putin,” Burns adds.

Carden argues that fear of Russia is approaching the level of hysterical propaganda, and questions whether it is even America’s problem in 2019.

“I’m not entirely sure I see the use of [NATO], the relevance of it, for America,” he says. “I would like to see America concentrate on a defensive alliance in its own neighborhood, given the rise of China, which is happening a lot quicker than people understand.”

“I’m not entirely sure our role on Europe is all that helpful,” Carden says. “If the Europeans want a defensive alliance, and they view a threat from Russia, they’re well within their rights to do that.”