Indonesia’s Muslim youth find new heroes in Instagram preachers

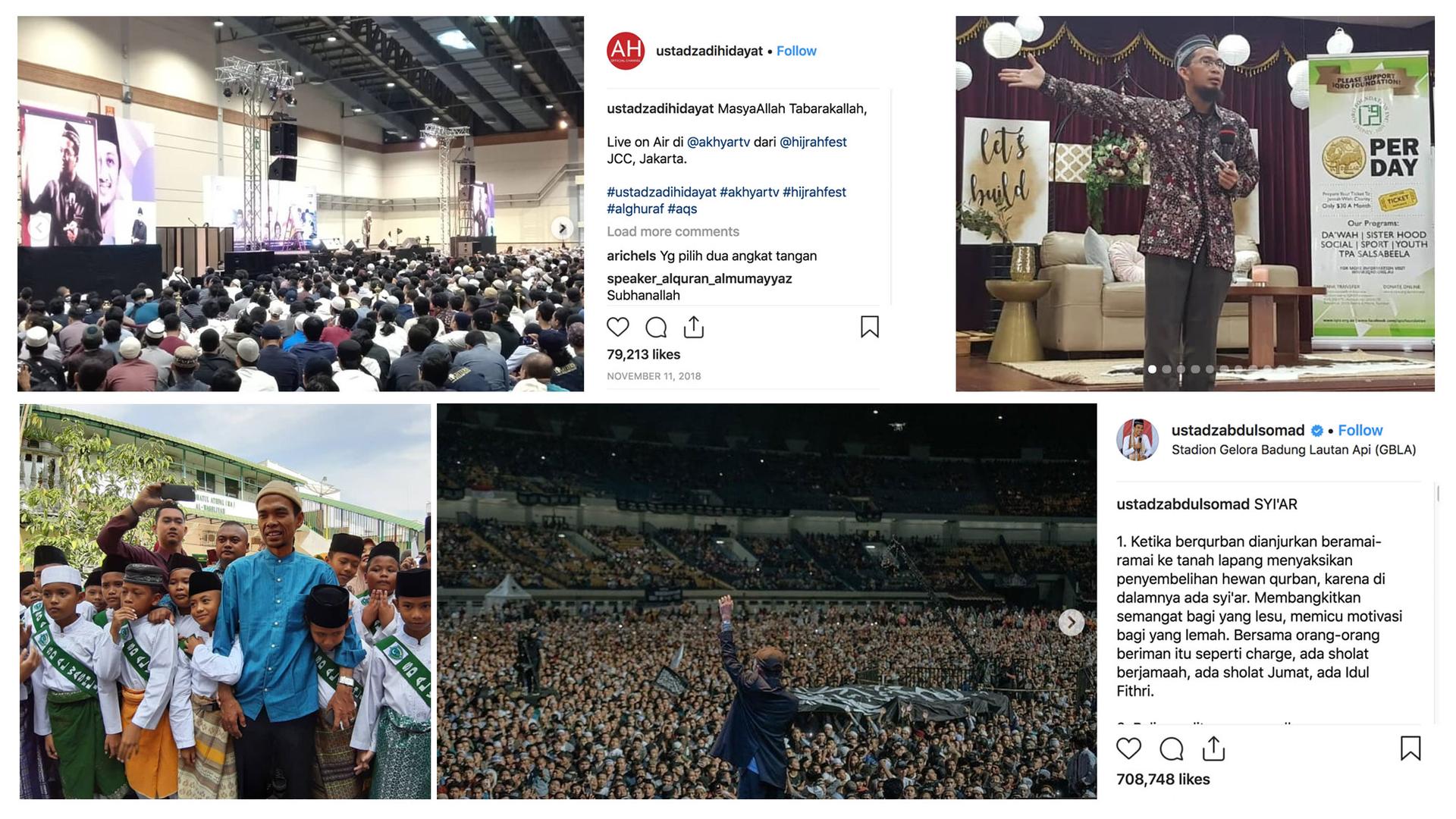

Top: Muslim cleric Adi Hidayat has a following of 1.5 million and growing on Instagram. Bottom: Muslim cleric Abdul Somad has a following of 8.3 million followers and growing on Instagram.

In Indonesia, the rise of rock star clerics on social media has fueled a movement known as hijrah, capturing the attention of Muslim youth seeking new ways to express their faith on social media.

Hijrah means “migration” in Arabic and refers to the Prophet Muhammad’s journey from Mecca to Medinah as one of the five pillars of Islam. But in Indonesia, some are embracing the word to illustrate a new wave of piety.

Indonesian celebrity Shireen Sungkar, who promotes the hijrah lifestyle as a “happy mom and wife,” has 14.9 million Instagram followers. Alyssa Soebandono, with 12.7 million followers, also models a modest hijrah-inspired life.

Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation with six different religions recognized with equal rights. Most Muslims practice Islam Nusantara, a form of moderate Sunni Islam mixed with local customs. But as a more conservative Islam spreads through massive social media networks, some wonder if a strict interpretation of Islam could shatter Indonesia’s pluralistic society.

Nearly 150 million of 268 million Indonesians actively use social media platforms and spend more than eight hours per day online, with more than three hours spent daily on social media alone, according to the 2019 Digital Report by We Are Social and Hootsuite. Facebook is also extremely popular, but Indonesian users now tap Instagram and YouTube.

HijrahFest, a three-day festival in Jakarta, has grown in popularity since its launch in 2018, primarily through social media. The festival is managed by the event company of Arie Untung, a former MTV VJ turned entrepreneur who decided that he’s done with worldly achievements and wants to focus on preparing for the afterlife through good deeds.

“After comparing different faiths, [I concluded that] the Quran is the absolute answer,” Untung said. According to him, social media plays an important role in today’s preaching and Quranic learning for the masses. Untung himself has 1.6 million Instagram followers.

Untung’s HijrahFest is like a pious version of the US’ SXSW where, instead of music, 12,000 festivalgoers network, explore a Muslim-themed trade show featuring modest fashion and halal cosmetics; get free tattoo removal services; and attend Quranic studies guided by the hijrah community’s top preachers. Appearances by the Hijab Squad, Indonesian female celebrities who promote a Sharia (Islamic law) lifestyle, alongside the Hijrah Squad, the male version, are also a highlight.

The movement became popular nearly 10 years ago among Indonesia’s urban youth underground — punks and skaters — who began to identify with radical, straight-edge Islam. Instagram accounts like Punk Hijrah and Pemuda Hijrah have emerged, featuring hijab-clad women riding skateboards and memes quoting Quranic verses. Cleric Hanan Attaki started Pemuda Hijrah and its media brand, Shift, with the motto “play hard, be useful, be plentifully rewarded, less sinning.” Attaki himself is an “Insta-preacher” with 6.9 million followers of his own, adored by the alternative scene in Bandung, Indonesia’s second-largest city.

“Mass Quranic learning gatherings today can be equated to concerts. All Indonesian bands combined couldn’t attract the mass as well as [Abdul Somad] and [Ali Hidayat].”

“Mass Quranic learning gatherings today can be equated to concerts. All Indonesian bands combined couldn’t attract the mass as well as UAS and UAH,” Untung said. He’s referring to two young clerics with foreign education credentials and charisma who have reached rock star status among Indonesian youth.

First, there’s Ustadhz (cleric) Abdul Somad, popularly known as UAS, an Indonesian cleric famous for incorporating comedy into his sermons and Quranic studies. UAS tours like a rock star and his 8.3 million followers on Instagram can track his travels.

A couple of years ago, UAS was accused of supporting Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, a hard-line Muslim organization that was disbanded by the government in 2018. That’s because of claims that HTI supports the re-establishment of an Islamic caliphate. It’s unclear how many supporters remain today. Rejecting the anti-nationalist accusation, UAS posted a selfie of himself on Instagram saluting the nation’s flag.

Then there’s Ustadhz Adi Hidayat, or UAH, with 1.5 million followers on Instagram. Amid a recent debate in Indonesia questioning the use of the word kafir (meaning infidel in Arabic) to define non-Muslims, UAH encouraged his followers on Youtube never to doubt the Quran, calling those who do “people with questionable faith.” The word is deemed problematic because hard-line groups use it to call out Muslim minorities such as Shiite, Baha’i, and Ahmadi, threatening to disturb Indonesia’s peaceful coexistence.

Related: The world’s largest Islamic group wants Muslims to stop saying ‘infidel’

UAH was born in Pandeglang in Banten province, known as a “hotbed” for Islamic extremism, and during his formative years in Pandeglang, West Java, he attended both public elementary schools and a now-defunct Quranic school. In 2010, UAH attended graduate school at Al-Dawa Islamiya in Tripoli, Libya, when the Arab Spring was brewing. By 2016, UAH launched his own TV channel, AkhyarTV, to broadcast his sermons.

While Muslim clerics have embraced Instagram with hijrah-inspired messaging, mobile apps and messaging apps also help the piously inclined to thrive.

Nina Fitria, 31, a mother of three and follower of UAH, says she became more committed to Islam during the last semesters of her university studies, after she met a “big sister” — a senior student who taught her about tawhid (the concept of monotheism central to Islam) and helped her improve her Quranic recitation and knowledge. Eventually, Fitria and her friends founded a Quranic WhatsApp group called Madrassa Khairunnisa for women only.

“We routinely meet online for Quranic recital, meeting once or twice a month on WhatsApp. It’s a moderated gathering. We invite a lecturer or ustadzah [a female cleric] to prepare a topic to reflect and discuss … upload some reading materials, followed by a Q-and-A session.”

“We routinely meet online for Quranic recital, meeting once or twice a month on WhatsApp. It’s a moderated gathering. We invite a lecturer or ustadzah [a female cleric] to prepare a topic to reflect and discuss … upload some reading materials, followed by a Q-and-A session,” Fitria said.

The group currently has 178 members. Fitria’s husband made an Android app that compiles Quranic study schedules in the Greater Jakarta area. According to Fitria, Instagram and Youtube are effective platforms for online religious studies, and she and her friends enjoy following various popular clerics on social media.

As parents, Fitria and her husband prohibit TV, opting instead for Youtube channels broadcasted through ChromeCast.

“There are less and less quality things to watch on TV nowadays, even the ads have bad influence on kids. To young kids, the best examples are their parents’ deeds. … My eldest often ask to watch the tales of the friends of the Prophet Muhammad … ” Fitria said.

Iqbal Dharmaputra, who grew up in a moderate Muslim family, said that he began pursuing a more pious lifestyle in 2014, shortly after becoming a father.

“To me, hijrah means ‘back to default.’ It’s a continuous process to learn the ultimate truth until the day we die. It’s an obligation to all Muslims. It’s crucial to commit and be guided properly through this process and not merely following a trend.”

Dharmaputra works for the postal service as a geographer but also started a small catering business with his wife in 2017 specializing in nasi kebuli, a rice dish similar to the Yemeni kabsa or South Asian biryani.

To ensure that his catering business is sharia-compliant, Dharmaputra attended Madrasah Al-Filaha, an Islamic agricultural school in Jonggol, West Java, where he learned to apply Islamic morals and ethics for farming and agriculture purposes. Lessons included how to slaughter his own goats — one of the main ingredients in nasi kebuli — the halal way.

“To me, hijrah means ‘back to default.’ It’s a continuous process to learn the ultimate truth until the day we die. It’s an obligation to all Muslims. It’s crucial to commit and be guided properly through this process and not merely following a trend,” he said, adding that his hijrah is a personal journey and the internet facilitated his journey to be a better Muslim.

“I watched a lot of sermons on YouTube. One of the first sermons I watched was about the meaning of life: how to be a good child for my parents, on family life.”

Among Islamic clerics, social media has been a catalyst to spread messages of peace as well as potentially harmful propaganda like amaliyah (sacrifice or suicide) and qital (physical war). In 2016, a woman named Dian Yulia Novi, a would-be suicide bomber who planned to bomb the presidential palace, said in an interview that she was inspired by the powerful status of clerics she encountered on Facebook.

Dharmaputra strongly objects to violence in the name of religion, however, and sees Islamic preaching online as part of one’s journey to pursue the truth.

“Our duty as Muslims even our Prophet Muhammad — peace be upon him — is to tell the truth. Faith is entirely Allah’s prerogative rights. It’s pointless to use violence to convert people. Too bad lately there are plenty of people who influenced others to perform qital in return of instant glory. Learning, understanding and applying Islam in life is way harder than earning glory through the use of violence.”

“[Conservative Muslims] are [a] minority in comparison, but they’re vocal. They’re well organized, highly political and work professionally on concepts and messages that are appealing to the public, through channels including on social media. They have clear targets [audiences], preaching to celebrities and children of VIPs.”

Most see hijrah as a benign, positive religious movement. However, a rising trend toward Islamic conservatism over the last 10 years is a concern for those tracking domestic terrorism tied to Islamic fundamentalism in Indonesia. While clerics like UAS and UAH have no known affiliations with extremists like ISIS or al-Qaeda, experts like Siti Musdah Mulia, a professor of Islamic studies at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, note a fine line between conservatism and extremism when it comes to the power of social media.

“[Conservative Muslims] are [a] minority in comparison, but they’re vocal. They’re well organized, highly political and work professionally on concepts and messages that are appealing to the public, through channels including on social media. They have clear targets [audiences], preaching to celebrities and children of VIPs.”

Musdah cautions against using the word hijrah because it’s been politicized to grab the attention of Indonesia’s youth. On many occasions, Indonesian President Joko Widodo has used the term to illustrate positive changes such as economic improvement and competitiveness, conflating development with the rise of conservative Islam.

Under Widodo, Indonesia has had to confront domestic terrorism often attributed to radicalization that happens through the internet. In 2009, Muhammad Jibril Abdul Rahman, a writer and publicist of extremist online material known as “Prince of Jihad,” was arrested for helping to channel funds to finance deadly double suicide bombings in Jakarta. He’s now a free man.

You can find him on Instagram.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?