Young Algerians have only known one president. Many are hopeful that will soon change.

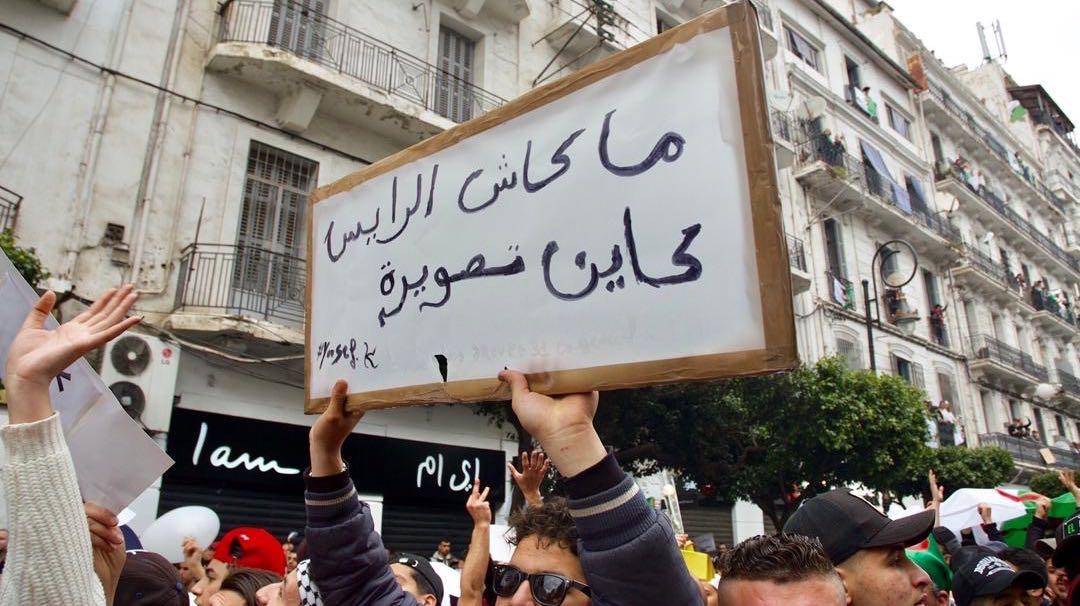

Hundreds of thousands of Algerians have been rallying for a new president since Feb. 22, 2019. This sign in Arabic reads: “There’s no president, there’s just a photo!”

Omar Djabi grew up only knowing one president his whole life.

The high school student says he sees Abdelaziz Bouteflika as a “sick and invisible” president of Algeria. Bouteflika has been in power for 20 years, but the 82-year-old hasn’t made any public appearances since he suffered a debilitating stroke in 2013.

On Tuesday, the country’s army chief, Ahmed Gaïd Salah, called on Bouteflika to step down, validating the nationwide protests that have gripped the country. He told Algerian television that he wants to apply Article 102 of the Algerian constitution that says that if a leader is too ill to rule, the parliament can ask him to step down.

That would allow for elections to be held in the coming months unless the president was to get better, according to The Telegraph.

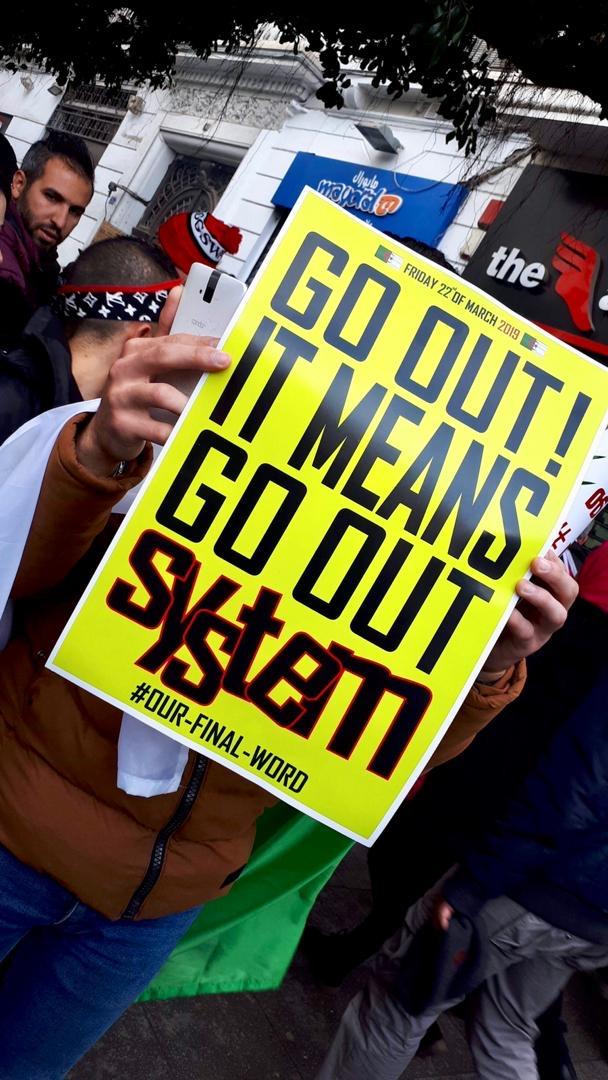

Amid growing pressure, on March 11, Bouteflika abandoned his plan to run for a fifth term. He delayed elections until April and promised a transition into a “new system.” Protesters say that’s not enough.

Djabi is among the hundreds of thousands of Algerians who’ve been protesting Bouteflika’s bid for re-election every week since Feb. 22. He goes downtown every Friday — he says he’s been to every rally except for one.

Despite Bouteflika’s longevity in office, he’s been largely absent from public life, at least during Djabi’s lifetime.

“The only way you see [Bouteflika] is if a letter he wrote is being read on the news. And you don’t even know if he wrote it.”

“The only way you see [Bouteflika] is if a letter he wrote is being read on the news. And you don’t even know if he wrote it,” Djabi said. “You always see other nations with young presidents. The Algerian people really want a president who can listen to our problems.”

Djabi says the rallies started on social media, mostly on Facebook, where activists would write rally dates and meeting times on top soccer team pages to grab Algerians’ attention.

At first, he and his father were surprised to see hundreds of thousands of Algerians in Algiers city center with helicopters overhead, he says. He could feel the earth shake from all of the chants and yelling. He and his father were both inspired to join in.

Before this moment, Djabi says he had lost hope in Algeria, an oil-rich country that has been marked by corruption and unemployment.

“But on that day [when he first saw the protesters], it was overwhelming because you see that people truly care about the country. They’re willing to go out and yell out their demands.”

Some do that with colorful, witty signs that riff off of the current state of affairs.

For Farah Souames, a documentary filmmaker in Algeria, the dark humor is the highlight of these protests.

“I was practically walking in the street and laughing,” said 36-year-old Souames, citing some of the funniest signs. “You know the Marlboro cigarettes? They said ‘mal barré’ in French, which means “you’re screwed.””

She says that comedy and sarcasm are key tools Algerians have used to overcome difficult times. There has been a lot of turmoil in Algeria’s past. In the 1990s, the army canceled parliamentary elections that triggered a 10-year civil war and left hundreds of thousands of people dead.

President Bouteflika oversaw the government transition in 1999 following the war. Today, the political system is dominated by veterans of an independence war against France that ended in 1962. (This timeline goes through key moments in the country’s rule.)

Many young Algerians say they want a new government, and more than a quarter of Algerians under 30 are unemployed.

“Eight years after the Arab Spring, observers hope that Bouteflika does not repeat the mistakes of his Arab counterparts who triggered war and displacement by responding heavy-handedly,” a CNBC report says.

“Our leaders still use fax machines. And the young generation is out there on Snapchat and Facebook Live. They’re broadcasting, for free, what’s happening on the streets of Algeria.”

“Our leaders still use fax machines. And the young generation is out there on Snapchat and Facebook Live. They’re broadcasting, for free, what’s happening on the streets of Algeria,” Souames said. “The government circle is so disconnected from the young generation.”

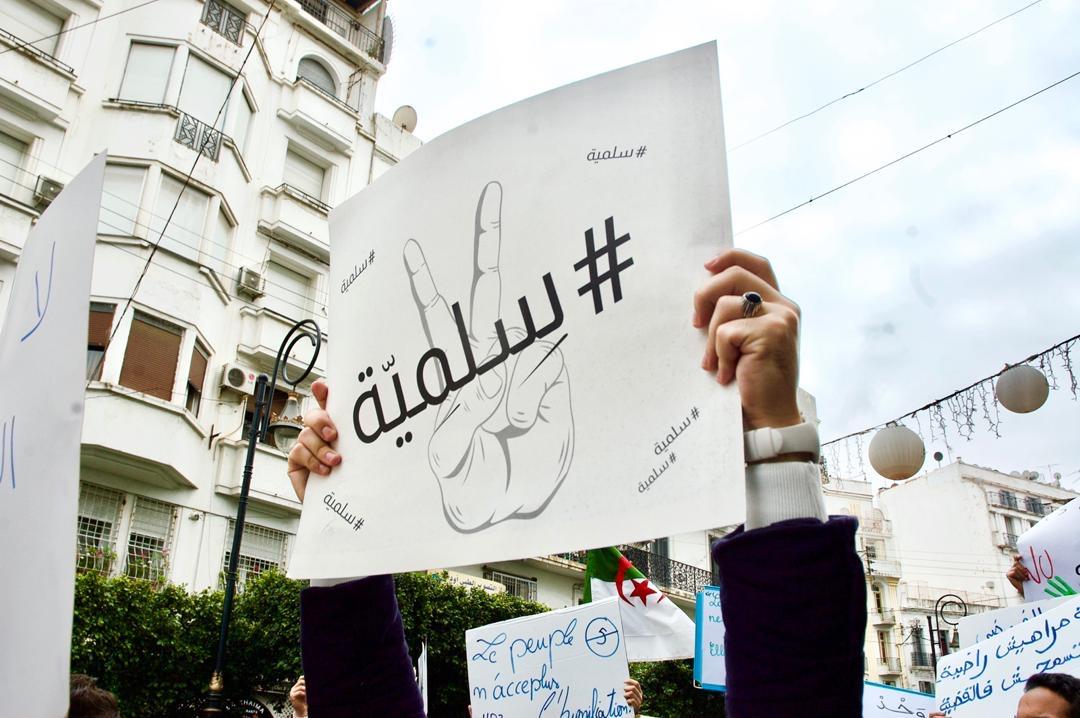

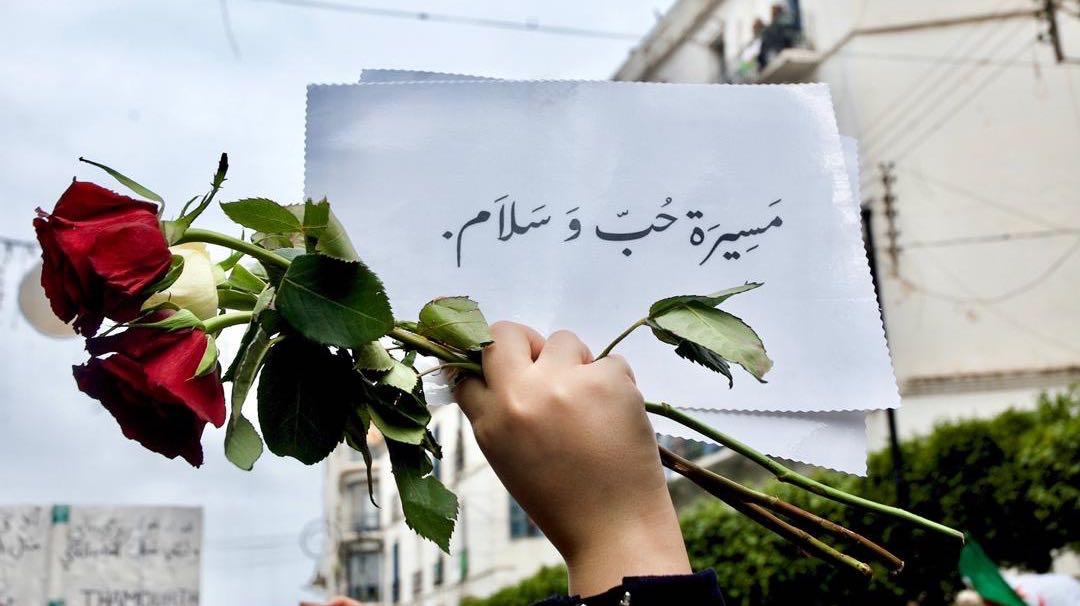

Souames credits the new generation for reclaiming the public space where protests have been forbidden since 2001. Algeria’s authorities have allowed the demonstrations to take place despite the ban on protests in the capital.

“We have the label of being very violent people during protests. But it’s nothing like what’s happening now,” said Souames, commenting on the peaceful vibe of the rallies.

Many Algerians are also reading the constitution for the first time because they lost trust in the electoral system and realizing that Bouteflika’s rule may, in fact, be illegal, she says.

“I think we were hopeless for a very long time. This fifth term was a wake-up call for everybody,” Souames said.

As for Djabi, he says he likes to share on social media to encourage his peers to take to the streets. He says that as a young person who only knows Bouteflika as president, change now feels possible.

“We’ve been told that we are the future of Algeria. We’ll be guiding it in the future,” said Djabi. “It’s important to be there now because the generation that is governing Algeria right now will be gone in the next 10 to 20 years and we will be the ones who will be here.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?