For black GIs in Saigon, ‘Soul Alley’ was an oasis of food and vice

“Soul Alley” is a documentary which examines a nightlife strip run by African American soldiers in wartime Saigon.

Bring up “Soul Alley” to the Vietnam War veterans who hung out on that storied lane in wartime Saigon.

You might hear about the nightclubs run by black soldiers who’d deserted the conflict. Or that tailor shop that sold the same sharp suits you’d find in Superfly-era Harlem.

And then there was the food.

“There was a soul food kitchen … with collard greens and black-eyed peas and hog maws and chitlins,” says Robert Rice, a veteran of the US-Vietnam War now living in Tennessee. “And fried chicken and red beans and rice. In Vietnam!”

These recollections were shared with a Houston filmmaker named Ted Irving. His documentary “Soul Alley: Children of the Dust, Streets of Ebony,” captures an oral history of this forgotten oasis for African American GIs.

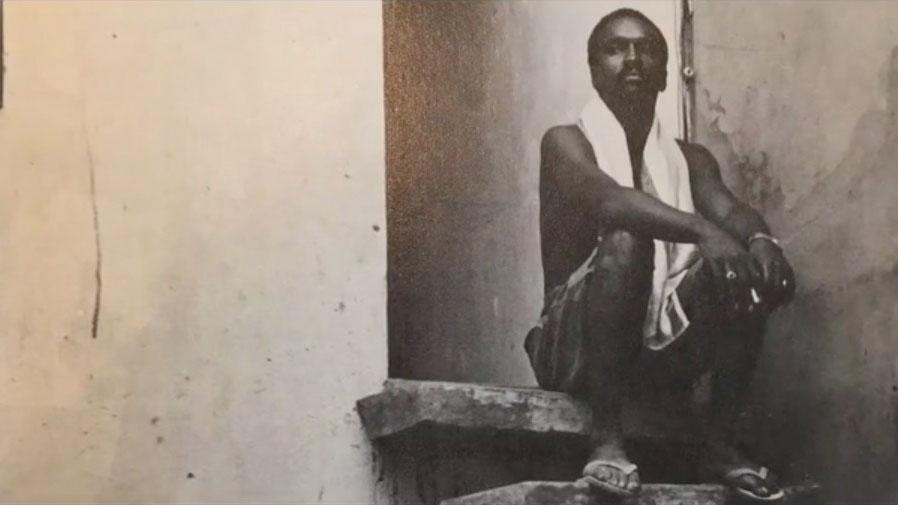

Soul Alley was a string of bars, clubs, shops and eateries that thrived in US-occupied Saigon. Reaching its heyday in the early 1970s, the strip was a little haven created by black GIs — some of whom abandoned the war to live there and run establishments with Vietnamese partners.

Related: LBJ knew the Vietnam War was a disaster in the making. Here’s why he couldn’t walk away.

For example, there was that soul food kitchen where the African American owner taught Saigon locals to make cornbread.

“The Vietnamese people could adapt, man, and cook anything you want,” says one veteran named Roland Starr. “Some places? You’d swear you were back in the States.”

So the black troops created their own sanctuary — one where the bars played Marvin Gaye instead of Waylon Jennings. A place where — as one former soldier explains in the documentary — whites were advised to come with black friends and not alone.

“We had clubs that catered to black GIs,” Starr says, “and whenever you’d see a white GI in there, it’s usually somebody who was brought in.”

Related: What really happened in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964?

At 49, Irving was just a toddler when Soul Alley was buzzing. Yet he’s been transfixed by the place since he saw a photo of the strip in a Time Life magazine as a kid. He’s devoted years to tracking down veterans who partied at Soul Alley and filming their reminisces.

The veterans’ typical reaction? “Aw, man! Big smiles,” Irving says. “These vets would look at me like, ‘How do you even know about that?’ It’s something they keep to themselves. Or didn’t even tell family about. It’s like a private joy.”

There’s a reason GIs might not mention Soul Alley to their mothers. These soldiers were consuming more than just candied yams. As with the nightlife spots catering to white troops, Soul Alley was a hub for booze, pot, brothels — all the things sought by combat-ravaged young men.

Black veterans told Irving they were fighting a two-front war: one against communist fighters in the jungle, another against white racists in their own ranks. In the documentary, a veteran named Abraham Wheeler says that, during the war, “you had to know your blackness … and you pulled together instead of pulling against each other.”

As he spoke to more and more vets, Irving came to understand how Soul Alley served as a release valve from the twin pressures of grueling combat and racial prejudice.

“There’s no therapist over there,” Irving says. “No one to let you lay on their couch. So they recreated this neighborhood of their own. Something to keep their minds off the horrors of war.”

What’s missing from the documentary, however, are the voices of women who were paid to pleasure these traumatized young men. Like all of Saigon’s nightlife zones frequented by American troops, sex workers were a prime attraction at Soul Alley, a place where Vietnamese women made a living in an economy destroyed by American bombs.

But these Vietnamese women, now in their 70s, proved extraordinarily difficult to locate and Irving says he ran out of funding before he could find and interview them. (Though complete, the film is awaiting distribution deals and is not yet viewable by the general public. Irving will announce release dates on the documentary’s official site.)

But he was able to find children conceived during the war by GIs with Vietnamese women — and he documents the torment they suffered once Vietnam was reunited and the Americans were driven out.

That communist victory also spelled out the demise of Soul Alley.

Related: The Tet Offensive shocked the nation and permanently changed US attitudes toward the Vietnam War

In modern-day Saigon, renamed Ho Chi Minh City after the US was driven away, there is almost no trace of the sanctuary that once was, according to Irving.

It was located near the US military’s now-defunct Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which has since been converted into Vietnam’s busiest commercial airport. Roughly five decades later, the place formerly called Soul Alley is a forgettable lane in the center of the city.

“It just looks like a normal street in Ho Chi Minh City,” Irving says. “There are people drying their clothes on lines. You know, a little cat here and a dog there. Just people hanging out on their steps.”