It’s July 16, 2018. Radio: “France is at war.”

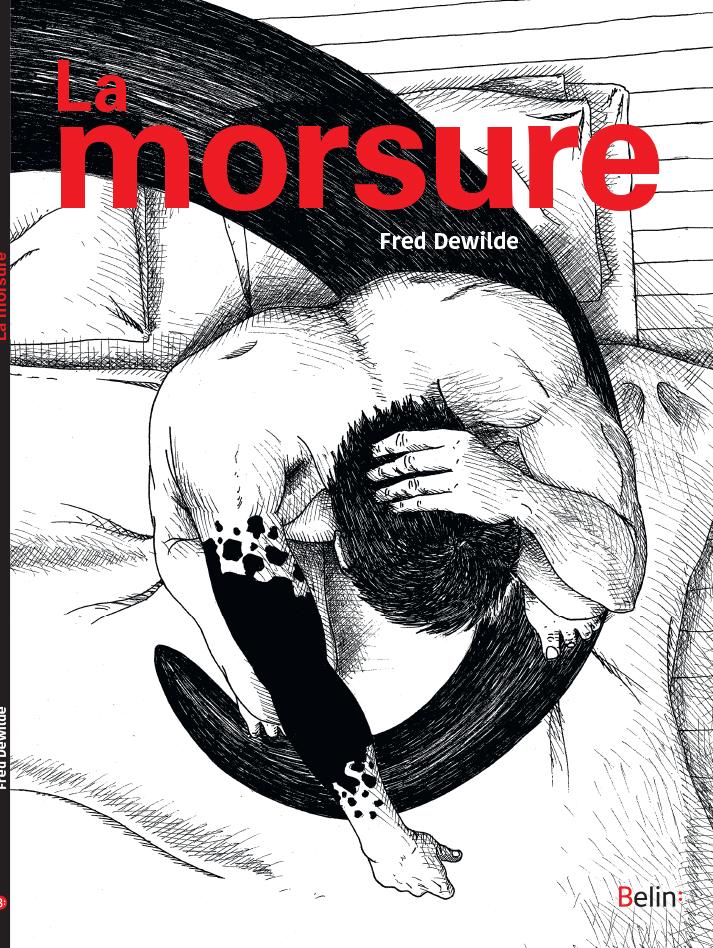

In the opening pages of Fred Dewilde’s latest graphic memoir, “La Morsure,” or “The Bite,” he arrives in the French countryside with his wife and children.

“It was really a wish to be quiet for three weeks,” Dewilde recalled, “with no Paris, no radio, no computers.”

This vacation, in July 2016, was the family’s first holiday since Dewilde survived the attack at the Bataclan concert hall by members linked to ISIS armed with guns and explosives. Simultaneous attacks across Paris, which took place three years ago this week, killed 130 people.

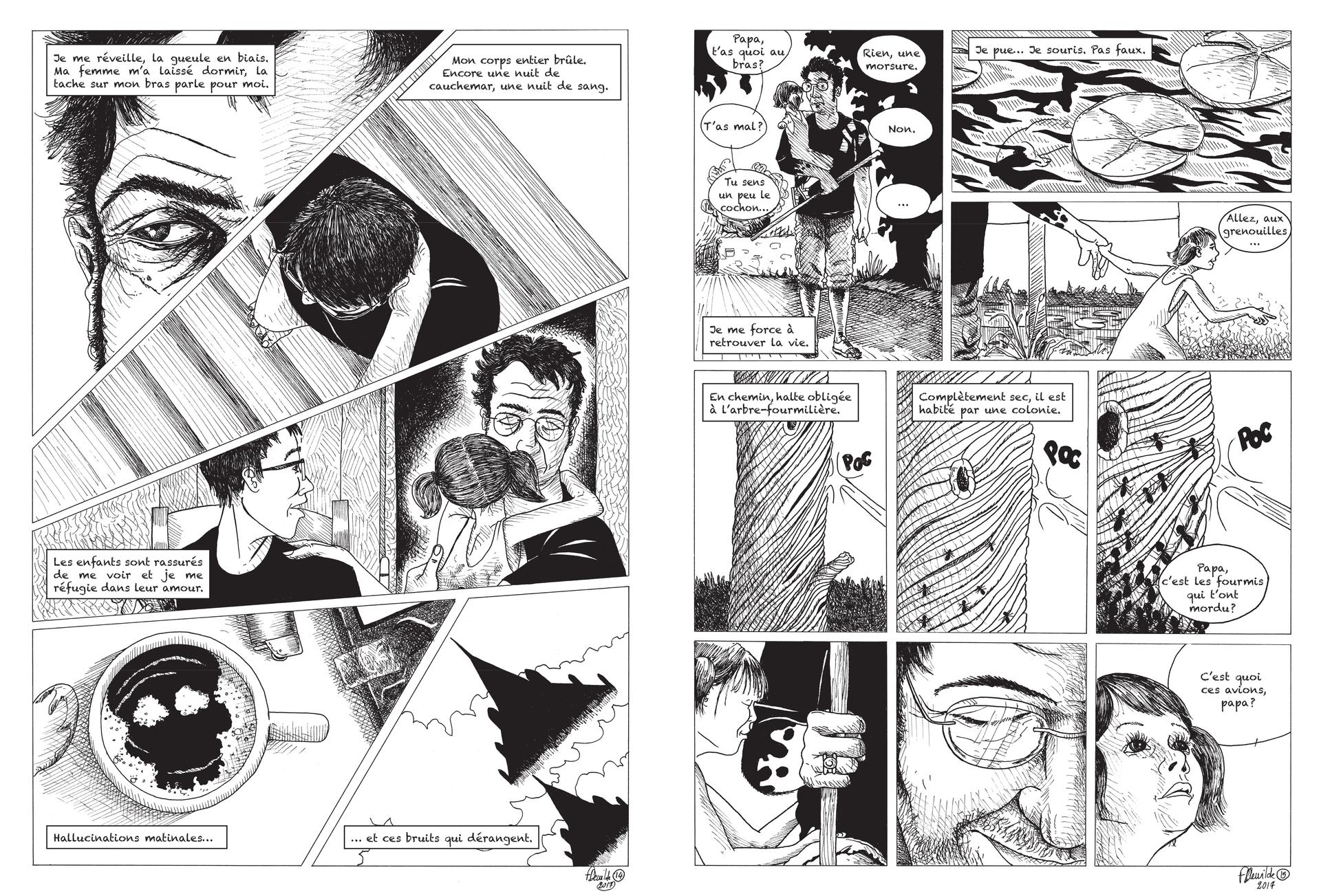

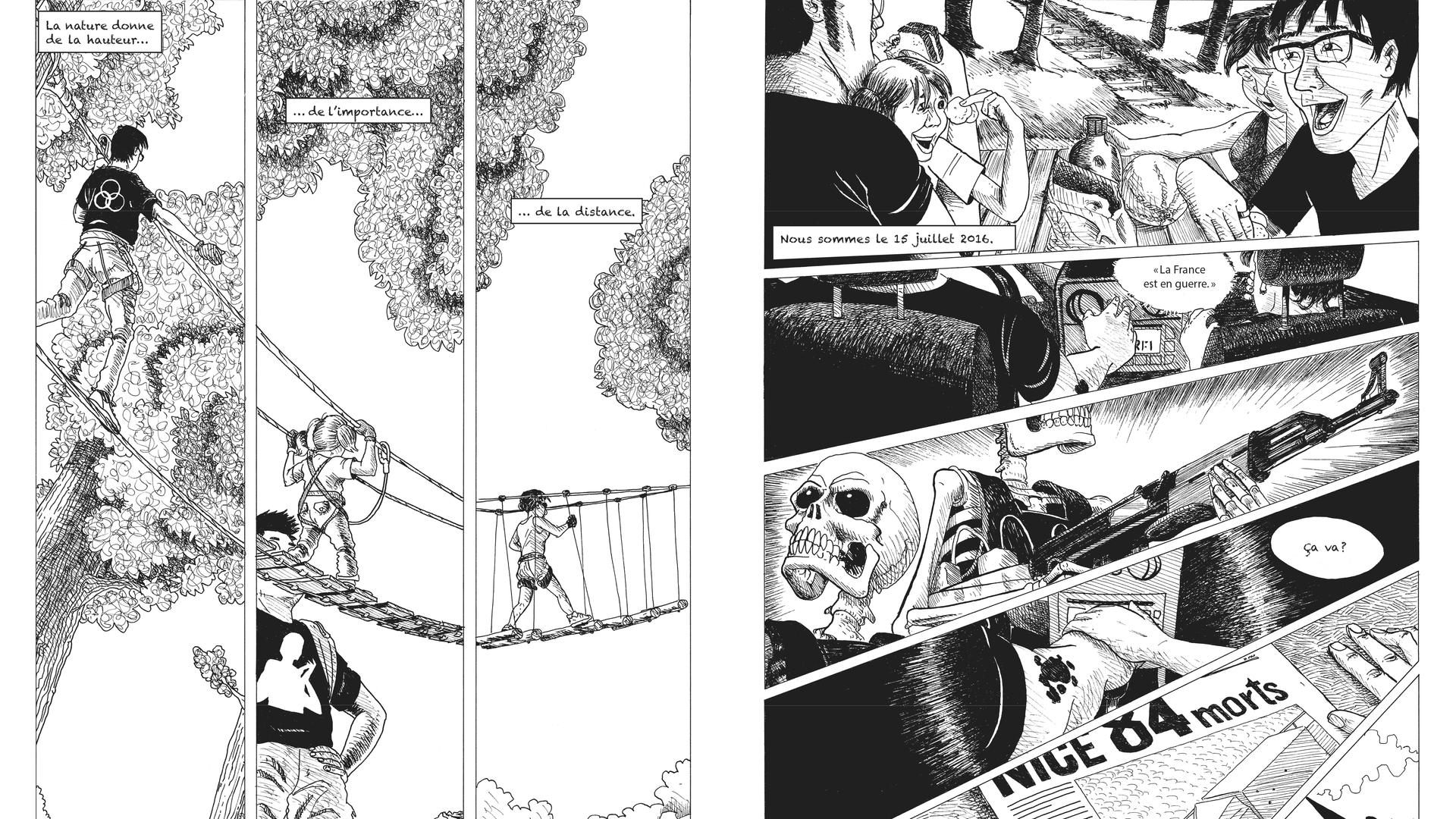

The reader sees Dewilde and his family walk in the woods, play cards, picnic, illustrated in detailed black and white drawings.

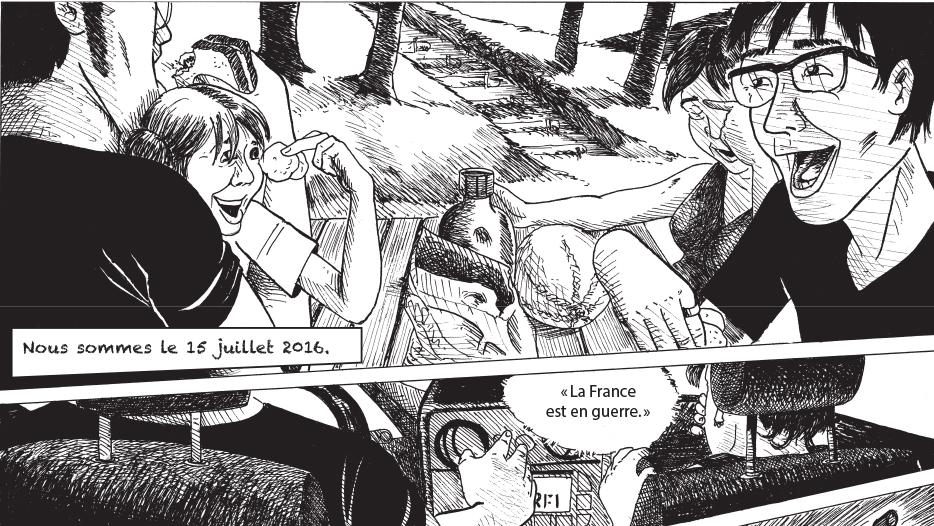

However, on July 15, 2016, Dewilde turned on the radio in his car with the intention of playing music from his phone, and learned of the attack that had taken place the night before.

An ISIS supporter had driven a truck through a crowd in Nice, France, gathered to watch Bastille Day fireworks, killing 86.

“After, it’s a shock, such [a] big shock,” recalled Dewilde, who found his memories of the previous November came crashing back.

In “La Morsure,” Dewilde leans on the idea that the attack on the Bataclan was like a snake bite, “to poison me in my mind and in my heart in my body,” he explained.

The snake, representing fear and hate that linger, reappears throughout the panels of his graphic memoir, with a black stain that expands and contracts from the site of the metaphorical wound on his arm with the darkness of his mood.

After the attack in Nice, the stain grows and threatens to overwhelm him. When he spends time with his children, it recedes but is always present.

Dewilde compared life ever since he survived the Bataclan to living on an elevator — constantly shifting positions.

“One day is really fine. One day is awful. One night is crazy and we don’t sleep. One night is absolutely marvelous.”

Seemingly small things can trigger his fear and anxiety.

“It can be something I saw on the TV, an emergency car passing in the street. It can be a plane that I heard in the kitchen,” said Dewilde.

Dewilde, now 51, worked as a medical illustrator for more than 20 years. He has spent the last two years, on and off, drawing these two books about the Bataclan and its aftermath, which he says has helped him to process his experience.

“If you want to forget something you have to work on it. It helps you to take distance,” according to Dewilde, who said his violent nightmares had lessened over the course of his work on the stories. “I think that drawing helps me. It’s the only way, to me, to explain the thing you are afraid of if you want to forget [them].”

He says his children have continued to help too. His youngest is 6.

“They don’t care,” he noted, what mood an adult is in. “You don’t want it but, ‘Daddy, I want to go playing to the park.’ ‘OK, let’s go to the park.’ And then going to the park, you hear a little bird singing.”

It reminds him, “life is outside.” And while he still has bad days, “more days now are good and less days are bad.”

He has also started work on a third book.