The Dominican Republic took in Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler while 31 nations looked away

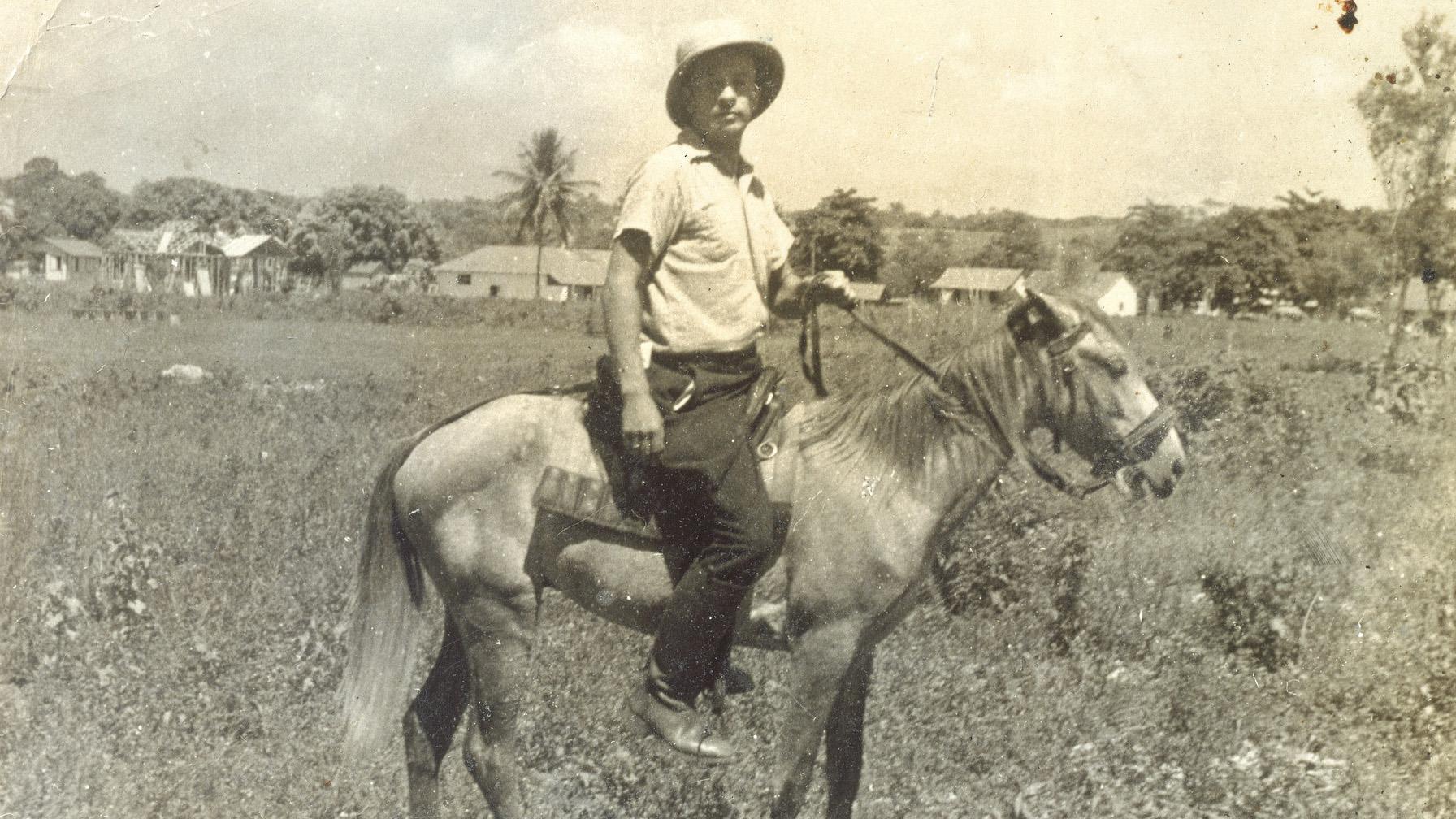

The Dominican Republic took in Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany in exchange for a promise to develop the land. Franz Blumenstein rides a donkey in Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940.

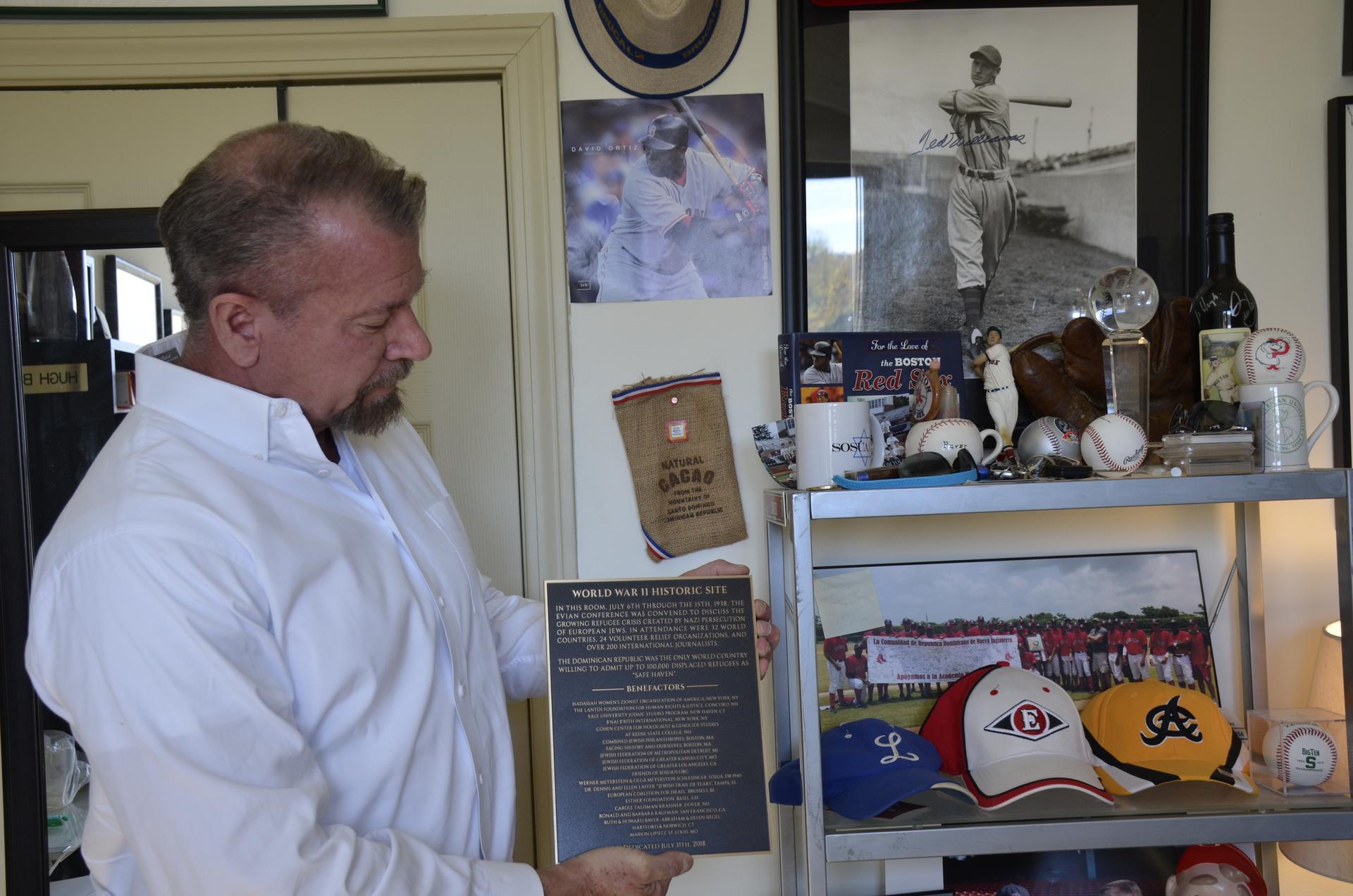

Hugh Baver is a former minor league baseball player, and in his late 50s, still looks to be in good enough shape to play today. His New Hampshire office is littered with baseball photos, signed gloves and knickknacks.

“I tend to collect individual, unique items that are just a little different,” says Baver.

Among the items he’s collected: a base from the final game of the 2013 World Baseball Classic. The Dominican Republic won that year. Baver decided to donate the base to the country, so, he flew to Santo Domingo and met with the famous Dominican player, Jesús Alou.

“We were just doing our usual talking about baseball and all that. And he happened to mention, ‘You might be interested to know that there’s this Jewish community that’s up on the north coast of the island, which originated from some conference or something like that,’” recalls Baver. “It was very vague, but it was enough that it stayed in my mind — very, very much still stuck in my mind.”

Related: This POW kept a secret diary that showed daily life in a concentration camp

So, Baver, who’s Jewish, started doing some research. He learned about the Évian Conference convened in France by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in July 1938, a meeting of 32 nations in France where only one country — the Dominican Republic — agreed to help settle German Jewish refugees.

Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo offered Jews safety for a promise to develop the jungle — hard work on poor soil. Historians also say Trujillo wanted to whiten up his country.

“They agreed to take up to 100,000 Jews and do that on very liberal terms — giving them 26,000 acres, a mule, a cow. To me, it was kind of like ‘Gilligan’s Island’ — my favorite show growing up — so, to me, it’s kind of like dropping in these people who don’t know how to farm onto an island.”

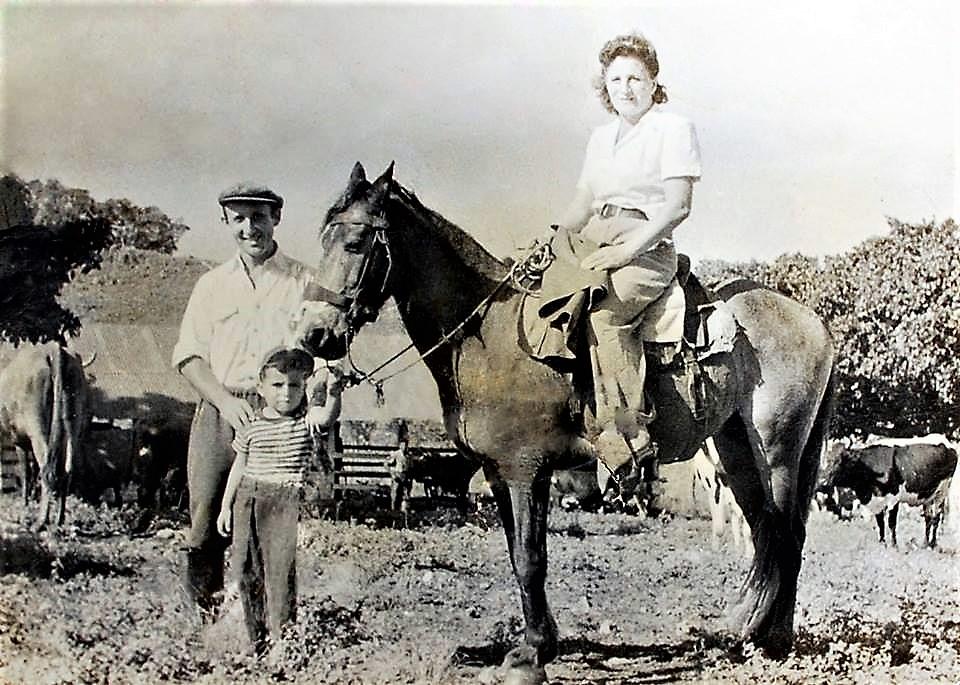

In the end, only about 700 German Jews were able to make it there. Rene Kirchheimer’s father was among the refugees who were sent to the outpost called Sosúa. He worked in the fashion industry in Germany, escaped to Luxembourg and then the Dominican Republic, where he found a much different life awaiting him.

“My father, when he had a farm, he raised cows and he raised pigs, as well, and he won a lot of prizes in the country fairs. I always say as a joke, they were very kosher pigs,” says Kirchheimer with a laugh.

Kirchheimer’s mother also came over from Germany, but wasn’t Jewish. Kirchheimer, who was born in the Dominican Republic in 1942, says it wasn’t so easy in Sosúa in the 1940s.

Related: What history reveals about surges in anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant sentiments

“It was very, very, very pioneer. I mean, you see the old Westerns, the movies — it’s very similar. The first few years, we didn’t even have electricity; that came later. We had, like, these kerosene lamps. And we had a big vessel to have cool water.”

A tough life, but Kirchheimer has fond memories. He says he had black and brown friends, and nobody cared that he was a Jew. Today, he says only a handful of the descendants of Jewish refugees are left in Sosúa. Most eventually left for the United States.

The agricultural experiment in Sosúa long ago transformed into a beach resort town. The small synagogue still stands there. They don’t have a rabbi, but Kirchheimer says for the holidays, they improvise.

“So, the older gentleman, he knows the routine; he knows how to hold a ceremony. He’s not a certified rabbi, but he’ll do.”

Sosúa’s Jewish community may have dwindled, but Kirchheimer would like people to know the history of his town.

“I would like the Dominican Republic to get the proper recognition for the gesture they had back at the Évian Conference in 1938. If everybody had done the same, a lot of Jews would’ve been saved.”

And that takes us back to New Hampshire and Hugh Baver. After he met Kirchheimer and the other remaining descendants in Sosúa, Baver became determined to spread their story.

Three years ago, Baver made his way to France and the five-star resort on Lake Geneva where the nine-day conference was held back in 1938.

“I wasn’t wearing my nicest clothes. I had on my Michigan State baseball hat, and I was just kind of a tourist,” says Baver. “And they were giving me a hard time even letting me in. And so, finally, I lied and said, ‘I’m a journalist from Boston here to report on a story.’”

Baver talked his way into getting the manager at the Hotel Royal to show him around.

“There wasn’t one person in the entire hotel who had any idea that the conference even ever took place there. They had nothing and nothing in any of their information. […] The hotel staff had no idea of it.”

Baver was astonished. After all, this was the spot where 31 nations turned their backs on Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler.

Four months after the Évian Conference — and 80 years ago, Friday — Kristallnacht occurred: a two-day assault on Jews throughout Nazi Germany. The name, Kristallnacht, which translates to “Crystal Night,” comes from the shards of broken glass after the windows of Jewish-owned stores and synagogues littered the German streets. At least 91 Jews were killed — and arguably many, many more — and some 30,000 Jews were arrested and taken to concentration camps.

The doomed Évian Conference is viewed as a beginning act of the Holocaust. In 1938, Adolf Hitler said that if other nations would take in Germany’s Jews, he would help them leave, “even on luxury ships.”

“Very shortly after that conference ended, Hitler got up on a stage and said, ‘Well, obviously, if no one cares about the Jews why should I?’ You know, it’s known as Hitler’s green light to genocide and the most fateful conference of all times for the Jews, but yet, nobody knows this. Not nobody — very, very, very few people,” says Baver.

Soon, many more will. Baver established a nonprofit, Sosúa75, to bring attention to the historical conference and settler colony that was founded in the Dominican Republic and regularly gives lectures.

And then there’s this: “This is the cast bronze plaque, which I had commissioned to be done and the hotel agreed to have this be affixed on the wall in the same room where the conference took place,” says Baver holding a plaque.

“I have to apologize if I get a little emotional, but it’s been a long road to get to this.”

Baver presented that plaque in France on Friday.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?