Brexit uncertainties cause Irish border communities to fear the worst

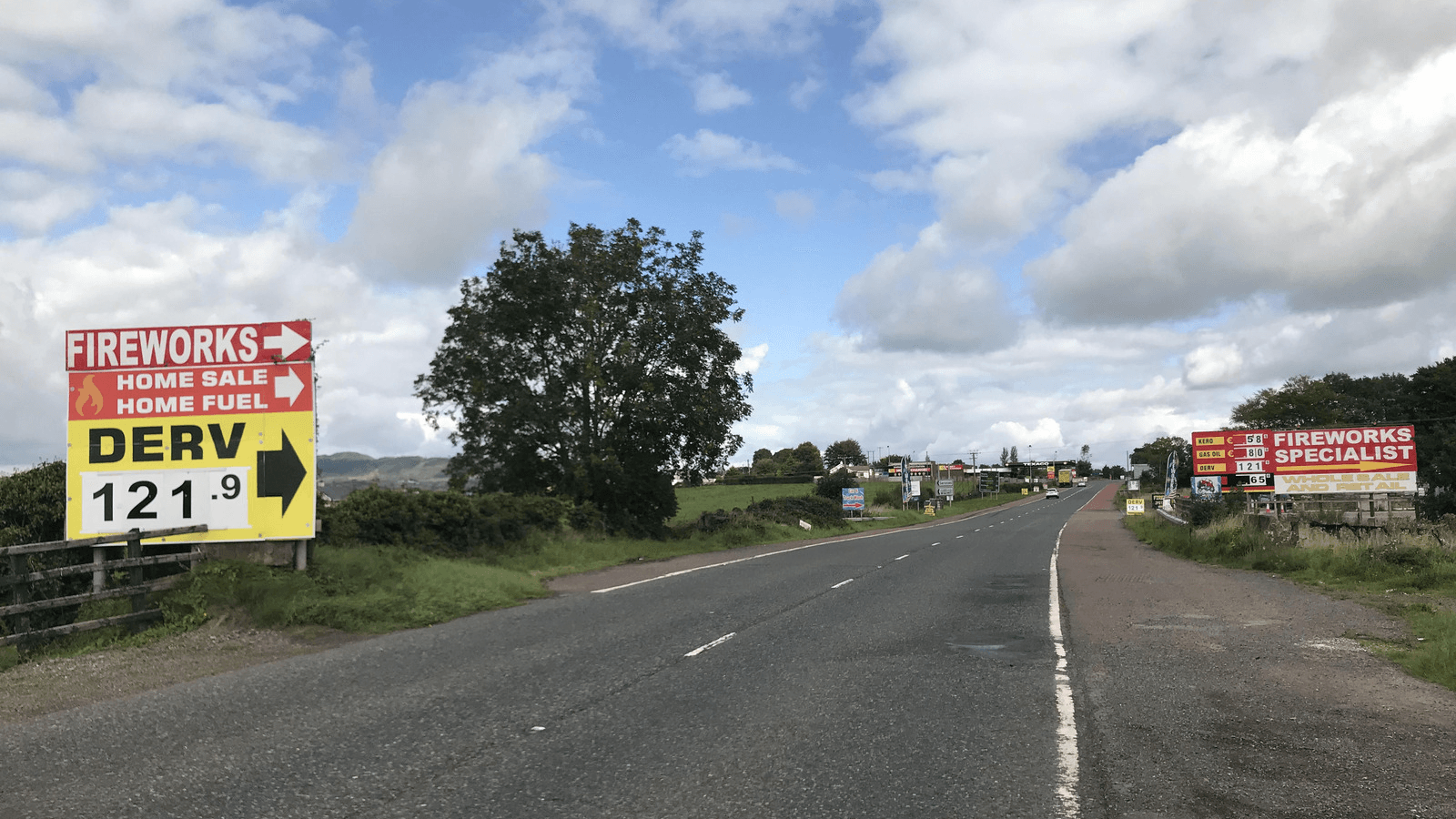

One of many unmarked border crossings between Ireland and Northern Ireland. After Brexit, however, these may once again become formal crossing points.

Martin McVicar gazes out over the factory floor where workers weave in and out of aisles piled high with machinery. The firm he directs, Combilift, is the largest global manufacturer of multidirectional forklift trucks. Designed, made and exported from County Monaghan, just on the border with Northern Ireland, Combilift was established in 1998, the same year that peace came to the island and the militarized border between the two territories started to be dismantled.

“Fifty-four [out of 550] of our employees live in the north and travel across the border daily to work — they don’t think of it as another country,” McVicar says. “If you ask the younger generation today where the border is, they couldn’t tell you. In their mind, they don’t see a physical border.”

And the border is largely invisible, 300 miles zigzagging through fields, streams, towns and even houses. Out of the 300 crossings, most do not even show a sign that you have crossed countries, save for the road signs — miles in the north and kilometers in the Republic. It’s a far cry from the Troubles — the three-decade period when rival unionist and republican paramilitaries warred over the political status of Northern Ireland — that saw the frontier strung with British Army checkpoints, soldiers and watchtowers.

The 1998 Good Friday Agreement saw the phasing out of this physical infrastructure, allowing people and goods to cross freely and unchecked. This was helped by the two countries being in the European Union Single Market and customs union for goods and services, largely removing any need for inspections at the border. In March 2019, Britain is expected to leave the European Union regulatory systems, leaving many to wonder how the currently open Irish border will be policed and how this could affect the fragile peace process.

A precursor to new Troubles?

As a child growing up in Monaghan, McVicar remembers having to lift his bicycle over the concrete checkpoints to go shopping in the north.

“I don’t think it’s going to end with a border like that but then any border is not in the interest of either side. But the reality is that if you want peace across multiple countries, the best way is easy movement of product and people. The minute you create borders, that’s not a way to create peace long term.”

With only six months until Britain is due to leave the European Union, the country is still yet to finalize a withdrawal agreement on the terms of its departure. One of the main sticking points is the British government’s failure to present the EU with a realistic proposal of how to keep the Irish border open. If no deal is reached, Britain would leave without any trade, regulatory and customs agreements with Europe and risk potential disruption at ports and borders.

Combilift currently exports its product to about 85 countries worldwide. The economic uncertainty of Brexit has caused McVicar to alter his supply chains accordingly.

“There’s no more certainty today than there was when the vote was cast two years ago,” he says. “We are actively looking for new suppliers from mainland Europe or Ireland rather than trying to increase our supply base from the UK because we don’t want to be subjected to import duty on our raw material coming in for products that we might export.”

Fabrication manager Jonathan McKenna, who has worked for Combilift for 18 years and lived in the north all his life, agrees.

“How to prepare for it? It’s the unknown. Even at the moment I’m wondering do I move to the south? Nobody’s really come up with anything concrete and people fear the worst,” he says.

Much anxiety over any interference with the border stems from Ireland’s painful recent past.

Dr. Katy Hayward, a reader in sociology at Queen’s University Belfast, explains how the border quickly became a flashpoint for violence:

“If you look at what happened during the escalation of the Troubles in the early 1970s when it was a customs border, customs officials and posts were targeted by paramilitary organizations, especially the IRA. So then customs officials became accompanied by armed police officers and eventually the British army. These areas would be most affected by any change to the status as they suffer from a legacy of underdevelopment due to being cut through by a border. The impact of conflict and division is only really beginning to be addressed now as a result of European integration and the peace process.”

Further along the border in County Armagh, by the roaring Belfast-Dublin highway, farmer Damian McGenity stands in a graveyard in the Republic of Ireland, pointing at the church which lies in Northern Ireland. Nearby, a row of houses contains rooms on both sides of the international frontier. For McGenity, whose group Border Communities Against Brexit has been erecting billboards across the region, the suggestion of any impediment to free flows over the border would ruin everything.

“There are so many layers to it,” he says. “My wife works in the south, we get fuel and food in the south, I buy farm supplies in the south. Socially, if you go out to a restaurant, or see a football game, you would typically go to Dundalk in the south. All of that would be disrupted.”

The nearby customs post at Killeen was a site of frequent bombings and shootings throughout the Troubles.

“Nobody wants to go back to any kind violence or trouble. Absolutely not. But when you create the situation or the possibility of it, you take the lid off the Pandora’s Box. It’s madness, when there is complete peace here,” McGenity added.

Over in Warrenpoint on the north side of Carlingford Lough, the sea inlet that forms the beginning of the Irish border, local businessmen Adrian O’Hare and Jim Boylan sip tea at the seafront Whistledown Hotel, recalling the bad old days when, during bomb threats, the town’s residents had to run to the beach. In 1979, Warrenpoint became the site of the biggest single loss of life of the British Army since World War II after a convoy was bombed by the IRA twice, killing 18 soldiers and one civilian.

Boylan and O’Hare are part of a group campaigning to build a bridge from Warrenpoint in the north to Omeath, on the opposite side. They say it will slash a journey that currently takes half an hour by car into a two-minute ride, revitalize trade and increase tourism to the area.

“The Good Friday Agreement is based on the whole concept of consent,” O’Hare says. “It’s accepted that, unless you consent to changing the political system, I’m not going to force you. And what we have now, bearing in mind people in Northern Ireland voted to remain in the European Union, the consent thing has gone out of the window.”

O’Hare also believes that the pre-existing disparity between the two entities — GDP per capita south of the border is more than double that of the north — heightened by Brexit, will cause further tensions as people in the north get taken out of the EU while the Irish Republic stays in.

“You take the low wage, democratic deficit and history of the two communities here while [the Irish] across the Lough seem to be doing a lot better, you have a recipe for trouble. The Good Friday Agreement was only possible because we were in the EU, one jurisdiction, and it just parked the issues. Peace ensued thereafter. Now you’ve disturbed that, you’ve got a border, a ‘them and us’ and you’ve got an opportunity for both sides to exploit the situation.”

Though the Irish border may be imperceptible, dividing lines in the Northern Irish capital are all too visible. After the Brexit vote, writer Garrett Carr decided to walk the entirety of the Irish border for a book project. He also lives in east Belfast, where some Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods are still separated by towering barricades referred to as “peace walls” — built to guard against sectarian killings throughout the Troubles.

Standing in the shadow of one such wall in the Short Strand district, says that he sees the connections between both areas:

“The fear of Brexit is that it will reharden the border and therefore other aspects of Northern Ireland’s social life will harden along with it. I think a lot depends on the border, and what happens in the cities sort of reflects the state of the border. The Good Friday Agreement softened the border and made life softer in the cities. What will happen when once again there is a confrontation, if no-one can say ‘the border’s not there’? That’s the real worry for a lot of people.”

Additional reporting by Mark Mistry.